Career Coaching Builds Confidence

Career Coaching Builds Confidence in Experienced Workers: What Governments Should Be Thinking About for Reskilling Initiatives Post-COVID – and Why

By Gerard Creaner, Sinead Creaner, Claire Wilson and Colm Creaner

Publication Date: June 2021

This article was published in the Behavioural Economics Guide 2021

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read):

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Relevant Background Information

- Adding Career Coaching to Technical Modules

- Assessing the Effectiveness of Job-Hunting Skills

- Pre-Pandemic Group 2017-2019: Establishing the Baseline

- Pandemic Cohort 2020 – Impact of the Pandemic on the Baseline

- Interpreting our Surprise Pandemic Data

- Implications for Future Government Reskilling Programmes

- References

- Further Reading

Abstract

With the end of the COVID pandemic in sight for first-world countries, government focus will shift to rebuilding economies. This will likely involve workforce reskilling initiatives for new jobs in thriving economic areas.

The authors have initial data to suggest that adding career coaching to technical training programmes builds confidence in experienced workers, and results in an overall positive impact on their outlook regarding the future. This is an unanticipated “bonus effect” in addition to the classic tangible metrics of reskilling programmes.

Since 2017, Confidence Metrics have been measured across 1,074 workers and, surprisingly, been found to remain high during 2020 despite the economic fallout from COVID.

The hypothesis relating to the “bonus effects” of more confident and resilient workers needs further study, but if shown to be reliable, including job-hunting skills within reskilling programmes, it could prove useful to both governments and the private sector alike.

Introduction

As vaccination roll out progresses (Public Health England, 2021) and cases begin to fall (Office for National Statistics, 2021), the COVID-19 pandemic in first-world countries is changing. Government focus will soon move from tackling a healthcare crisis, to tackling the looming economic one (Beckett, 2021). A large part of this effort will involve retraining displaced workers for new jobs in thriving local industries.

This paper examines the practical experience and research background of one private training provider with over 10 years’ experience reskilling mid-career workers for employment in a growing technical and highly regulated industry.

What’s more, that experience is in an online environment and working alongside a long-running, currently active government retraining scheme (Higher Education Authority Ireland, 2021).

This paper offers insights into how to maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of such programmes.

Relevant Background Information

The demographics of the 1,074 experienced workers (2017-2020) are as follows:

- Based in Ireland

- Taking same reskilling course

- 38% female; 62% male

- 45% <40 years; 55% >40 years

- 28% employed; 72% unemployed

They came from a range of other industries, including food and beverage, finance, administration, healthcare and construction.

All received Irish Government funding through the Springboard+ reskilling initiative (Higher Education Authority Ireland, 2016), whereby the government paid either 90% or 100% of their course fees.

Our reskilling programmes have been delivered online for over 10 years now. The team utilises an action research approach to updating course offerings in response to new evidence or participant feedback, whereby the authors work through a seven-step process in a continuous cycle – as per Ernest Stringer’s Action Research Interacting Spiral (Stringer, 2007).

Due to the online delivery method, programmes were not impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic or the associated social distancing requirements. This is particularly relevant, since Ireland spent the majority of time from March 2020 onward in level 5 lockdown due to the ongoing pandemic (Department of the Taoiseach, 2020).

The programmes are all designed to transition experienced workers from other industries into the pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturing sector, which offers high-paying, high-tech jobs in a stable, secure and growing sector in Ireland (Halligan, 2016).

During the pandemic, the pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturing industry in Ireland remained open, and hiring (Creaner, 2020). There are over 62,000 people employed directly by this sector, and a further 120,000 employed indirectly (GetReskilled, 2021). In total, this accounts for almost 10% of the Irish workforce (IDA Ireland, 2021).

Adding Career Coaching to Technical Modules

Our business was initially delivering technical modules to provide experienced workers from other sectors with the industry-specific information they needed to secure an entry-level role.

In 2016, we realised there was more we could do to improve the success rate of our participants securing employment in the industry.

We observed that many workers had poor job-hunting skills, particularly when moving into a new or an unfamiliar sector. While almost everyone thinks they know how to job hunt, it’s our experience that very few can actually implement best practice in this regard.

To overcome this issue, we developed a career coaching strategy to complement the technical learning, which included a “Job-Hunting Skills” module for the experienced workers on our programmes.

The module was designed to walk the experienced worker through finding their ideal job within this new sector (aligning with relevant skills from their work experience to date) and then through the job-hunting process, step-by-step – including where to look, how to network, how to write a CV and understanding key interview skills.

After spending five weeks studying guided activities (approximately 50 hours of study time), workers would submit an assignment that simulated a job application and recruitment process. They were given three real historical job adverts to choose from and complete tasks that included tailoring their CV, writing a cover letter, considering their relevant network contacts, writing follow-up emails and scripting sample interview answers as if they were applying for one of these jobs.

Assessing the Effectiveness of Job-Hunting Skills

We assess the effectiveness of this Job-Hunting Skills module in four separate ways:

- Knowledge and Ability to Implement: Using a multiple-choice assessment of 10 questions, participants choose which answer most closely matches their approach to various aspects of job-hunting, following the action mapping approach suggested by Cathy Moore (2007). Scores do not count towards their grade in the module, and participants are asked to answer honestly. Scores show how well their answers align with current best practice job-hunting advice. This is the first task in the module and is revisited as one of the final tasks, to capture the change in their knowledge and understanding.

- Module Feedback: The experienced workers give both quantitative (“star rating” out of 5, in response to the question “How would you rate your overall experience of the Advanced Coaching programme so far?”) and qualitative feedback at the end of the Job-Hunting Skills module.

- Successful Outcomes: We measure “successful outcomes” for all experienced workers on our programmes. The successful outcomes are defined as a participant either finishing the course, getting a job or both. This snapshot of success is taken within six months of the course finishing.

- Confidence Metrics: We capture feedback from participants at the end of their reskilling programme – a key feature of this is a range of “Confidence Metrics” through which the participants’ confidence is assessed across a range of future aspirations.

The rest of this paper will first discuss the baseline for these effectiveness measures, by considering results from a “pre-pandemic group” (experienced workers reskilling between 2017 and 2019), before assessing how that effectiveness has been affected by the pandemic, by outlining the results of our “pandemic cohort” (experienced workers reskilling during 2020).

Pre-Pandemic Group 2017-2019: Establishing The Baseline

Our pre-pandemic group consists of a total of 923 experienced workers: 329 in 2017, 315 in 2018 and 279 in 2019.

A total of 597 of these completed the end-of-programme survey: 217 in 2017, 197 in 2018 and 183 in 2019.

In 2017, the Job-Hunting Skills module was introduced as an optional module, with 20% of experienced workers opting in.

In the latter half of 2018, and after successful proof of concept, the module was made mandatory. Since the 2018 group includes a mix of both opt-in and mandatory module participants, a total of 57% of all 2018 participants completed the module.

In 2019, the module was made mandatory for all experienced workers, so 100% of participants completed it.

The effectiveness measures were as follows:

1. Knowledge and Ability to Implement

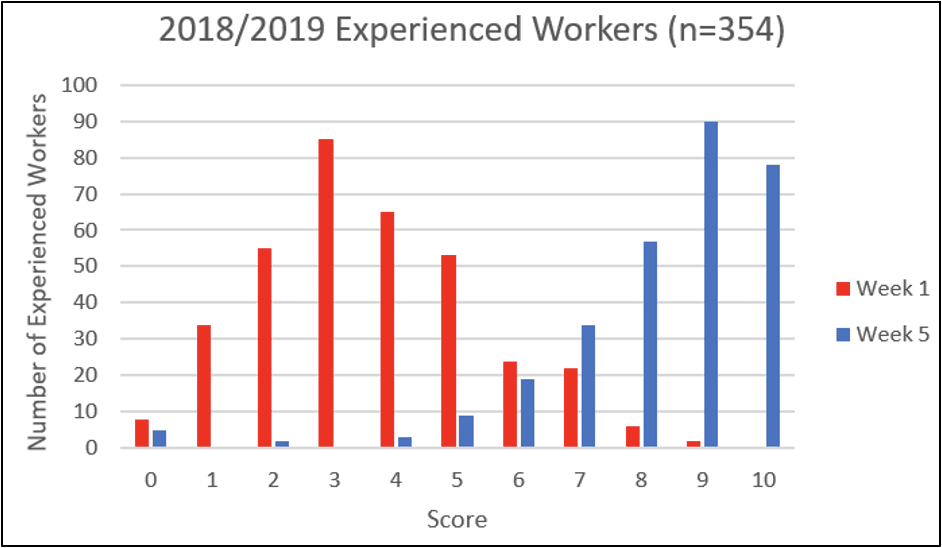

The multiple-choice assessment was introduced within the module in 2018, so the data for Figure 1 are gathered from 2018 and 2019 participants only.

Figure 1 – Results of knowledge and ability to implement assessment (2018-2019)

From Figure 1, we can see a change from the week one assessment scoring of experienced workers’ knowledge and ability to implement best practice job-hunting techniques (mean=3.85) and their week five scores (mean=8.51), which is statistically significant (t=30.89, p<0.05).

This suggests that the module is successfully equipping participants with knowledge of job-hunting best practice and the ability to implement it successfully.

Moreover, the initial assessment serves as an anchor by which the experienced worker can see their own progress over the course of the module, thereby serving to increase self-belief in their new skills.

2. Module Feedback

Table 1 shows the average results of the participant star ratings (out of 5, which were captured at the end of module feedback from a total of 182 participants during 2018 and 232 during 2019. Module feedback was only implemented in 2018, so there are no data available for the 2017 participants.

| 2017 | 2018 (n=182) | 2019 (n=232 | |

| Quantitative Feedback: Average Star Rating out of 5 | N/A | 4.29 | 4.18 |

| Qualitative Feedback: Participant Feedback | "When I started this module, I thought I knew something about job-hunting, but after completing this module I realised I really didn't know anything." "This module is amazing! I never realised how many mistakes I made before as regards job-hunting. I feel so much more confident now that I have completed this course, and the process will stay with me forever." |

||

Table 1 – Pre-pandemic module feedback

We can see from both qualitative and quantitative participant feedback that the experienced workers enjoyed the module, with many saying they found more value than they expected.

From analysing the qualitative answers and talking to participants, we established that there appears to be a common theme in terms of experiencing of the module:

- Believing they already know best practice at the start of the module

- Being shocked at how low they score on the knowledge and ability assessment – the first task in week one

- Approaching the module with a much more open mind to learning new techniques for job-hunting

- Taking on board these techniques, practising them and gaining confidence in how to implement them

- Reaching a level of confidence that now accurately reflects their knowledge and ability to implement best practice job-hunting techniques

We were struck by how similar this common experience mirrors that of a classic Delusion of Competence (Kruger & Dunning, 1999), and how effectively the module appears to help move participants through each stage.

This was particularly interesting given that the optional opt-in was low (20%) – even when we told people that previous participants found great value in the module. It seemed like most believed they were the exception that truly already knew best practice.

We therefore took the decision to make the Job-Hunting Skills module a mandatory part of the programme.

3. Successful Outcomes

To compile the dataset in Table 2, we analysed the survey results from the three pre-pandemic years.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Finished full programme | 142 (65%) | 140 (71%) | 118 (64%) |

| Got job … specifically in pharma/med device | 115 (52%) … 58 (50%) | 90 (45%) … 56 (62%) | 83 (45%) … 54 (65%) |

Table 2 – Pre-pandemic successful outcomes

From the above, it is evident that the move from optional participation in the Job-Hunting Skills module to mandatory participation had a statistically significant impact of increasing the percentage of experienced workers who successfully found a job in the pharmaceutical or medical device industry within six months of the programme finishing (moving from 50% to 65%; Z=-2.11, p<0.05).

We can deduce, therefore, that the Job-Hunting Skills module equips students with effective job-hunting skills for their target industry and gives them the confidence to pursue those high-tech jobs, even without previous industry experience.

As a result of this evidence, we were happy to continue with our decision to keep the module mandatory.

4. Confidence Metrics

Confidence metrics were assessed during the end-of-programme survey for all three years. Participants were asked whether their confidence across a range of future aspirations had increased or decreased as a result of participating in the programme[1].

The nine aspirations assessed were:

- Engagement with lifelong learning

- Ambition for career advancement

- Ambition to get a better-paid job

- Enjoyment of further study

- Confidence in the future

- Determination to succeed

- Motivation for getting a rewarding career

- Confidence in future job security

- Ambition to achieve mastery in their chosen career

For ease of interpretation, this data has been summarised into the average number of workers reporting an increase in confidence, averaged across all nine metrics.

| 2017 (n=217) | 2018 (n=197) | 2019 (n=183) | |

| Job-hunting module participants | 83% | 92% | 93% |

| Non-job-hunting module participant | 80% | 86% | N/A as Job-Hunting Skills module made mandatory |

Table 3 – Pre-pandemic confidence metrics

While this was not a deciding factor in making or keeping the module mandatory, we could see a statistically significant increase in confidence when comparing those who participated in the Job-Hunting Skills module in 2018, against those who did not do so (Z=2.42, p<0.05).

We hypothesised that the 2018 iteration of the Job-Hunting Skills module was increasing confidence by reducing participants’ uncertainty. The module takes a large and complex process and breaks it down into manageable, bitesize pieces. We believe that, in doing so, participants are left feeling like they understand the job-hunting process better and are motivated by their own ability to complete each piece successfully.

Not only does this seem to give participants hope of finding a job during their current job search, but we believe it also provides them with reassurance in terms of their ability to job hunt successfully in the future, if they need to do so. This, in turn, appears to have a positive effect across the range of future-looking Confidence Metrics.

Pandemic Cohort 2020 – Impact of the Pandemic on the Baseline

Our pandemic cohort consists of 151 experienced workers, each of whom took a reskilling programme in 2020. All participants were given the Job-Hunting Skills module, and 97 of them completed the end-of-programme survey.

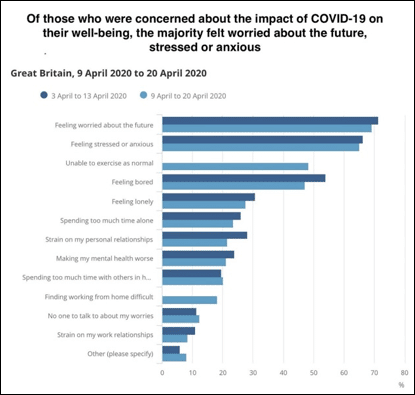

Of the four effectiveness measures, we expected the first three to remain relatively unchanged by the circumstances of the pandemic and its economic fallout. We did, however, hypothesise that we’d see a notable decrease in the Confidence Metrics, as the UK Office for National Statistics was reporting that the population felt more worried about the future, as well as more stressed and anxious during the lockdowns (Office for National Statistics, 2021).

The observed effectiveness measures for this group were as follows:

1. Knowledge and Ability to Implement

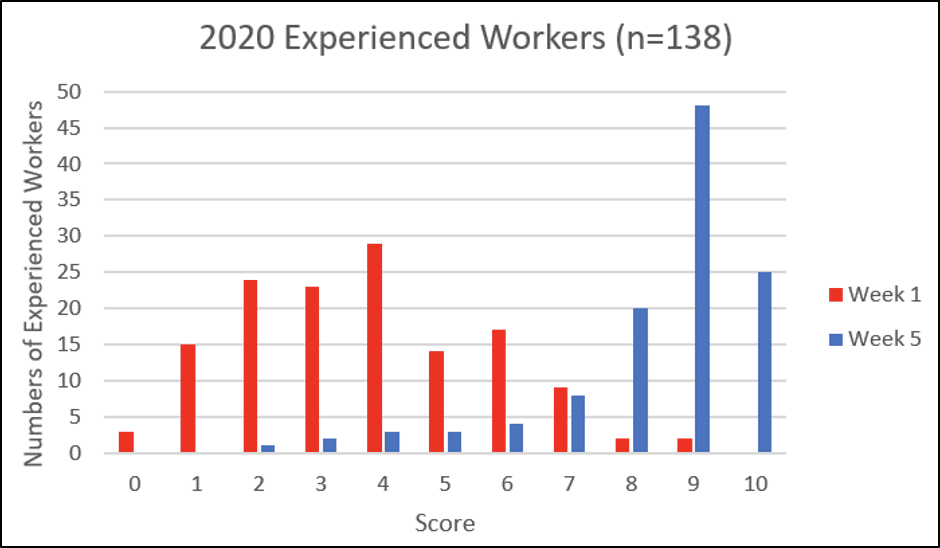

Figure 2 shows results for the knowledge and ability to implement assessment for the 2020 group.

Figure 2 – Results for the knowledge and ability to implement assessment (2020)

As expected, we once again see a shift in the mean scores of the experienced workers’ knowledge and their ability to implement best practice job-hunting techniques between week one (mean=3.98) and week five (mean=8.59), which is statistically significant (t=-18.93, p<0.05).

This confirms that the module is still successfully equipping participants with knowledge on job-hunting best practice and the ability to implement it successfully, independent of the unique destabilising effects of the pandemic.

2. Module Feedback

Table 4 shows the average star ratings from the end-of-module feedback from 97 experienced workers in 2020.

| 2017 (n=217) | 2018 (n=197) | 2019 (n=183) | 2020 (n=97) | |

| Quantitative Feedback: Average Star Rating out of 5 | N/A | 4.28 | 4.18 | 4.31 |

| Qualitative Feedback: Participant Feedback | "At first, I thought this would not be something important to me… but now I see it is even more important than technical skills." "When I first began this module, I was skeptical, because I thought my CV and cover letter were good enough and I felt it was just the lack of experience as the reason why I wasn't securing employment in the pharmaceutical industry. Now that I have completed this, I can see how wrong I was." |

|||

Table 4 – Pandemic module feedback

Similarly to previous years, we can see from the participant feedback that the experienced workers enjoyed the module and took a good deal of value from it.

Qualitative feedback again shows that participants are still moving through a cycle of not initially being motivated by the prospect of the module, being shocked at their low current knowledge of best practice, learning and practicing best practice, before reaching an appropriate level of confidence.

3. Successful Outcomes

In Table 5, we analysed successful outcomes reported in the end-of-programme survey.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| Finished full programme | 142 (65%) | 140 (71%) | 118 (64%) | 78 (80%) |

| Got job … specifically in pharma/med device | 115 (52%) … 58 (50%) | 90 (45%) … 56 (62%) | 83 (45%) … 54 (65%) | 39 (40%) …. 23 (58%) |

Table 5 – Pandemic successful outcomes

As expected, there was no significant difference in the percentage of people getting a job (in pharma/med device or not) when we compared 2020 to 2019, as the industry kept hiring throughout the lockdowns.

There was, however, a statistically significant increase in the percentage of experienced workers finishing the programme, from 64% in 2019 to 80% in 2020 (Z=-2.57, p<0.05). Since the programme is delivered fully online and many workers were furloughed at home during this time, this is perhaps an unsurprising outcome.

4. Confidence Metrics

We assessed the same nine aspirations as previously detailed.

As before, for ease of interpretation the data have been summarised into the average number of workers reporting an increase in confidence, averaged across all nine metrics.

| 2017 (n=217) | 2018 (n=197) | 2019 (n=183) | 2020 (n=97) | |

| Job-hunting module participants | 83% | 92% | 93% | 93% |

| Non-job-hunting module participant | 80% | 86% | N/A as Job-Hunting Skills module made mandatory | N/A as Job-Hunting Skills module made mandatory |

Table 6 – Pandemic confidence metrics

Unexpectedly, our hypothesis of a fall in Confidence Metrics was not seen in the data. In fact, the “bonus effects” of the Job-Hunting Skills module stayed the same as 2019 (at a high of 93%) and appeared to be independent of the economic impact of the pandemic.

Our belief in the module being in the best interests of our participants, and the decision to make its inclusion mandatory, means that we don’t have a control group (who didn’t take the module) to compare against. Nevertheless, we believe the ONS reporting of the population feeling worried about the future, as well as stressed and anxious – see Figure 3 (Office for National Statistics, 2021) – provides an appropriate basis for comparison.

Figure 3: ONS – Impact of COVID-19 on the adult population in Great Britain, April 2020.

Source: Office for National Statistics – Opinions and Lifestyle Survey

We shall now consider possible explanations for this surprising occurrence.

Interpreting our Surprising “Pandemic Data”

Based on the reports from the UK Office for National Statistics, our team had hypothesised that our Confidence Metrics would reduce within our “pandemic cohort” in 2020 – but in fact they stayed the same as the previous pre-pandemic group.

We wanted to explore why this might be happening.

There are some reasonable explanations that immediately come to mind for why confidence may have remained high for the pandemic cohort:

- These experienced workers were moving into the pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturing industry in Ireland, which continued to hire throughout the lockdowns (NIBRT, 2020)

- The experienced workers were all beneficiaries of a government-funded reskilling programme (Higher Education Authority Ireland, 2021), so they faced little or no financial risk

- Both the technical programme and the Job-Hunting Skills module were purposely developed to be delivered in an online format, and so studies could continue independently of lockdowns

However, as we had already observed increased Confidence Metrics to the same level within the pre-pandemic cohort – and shown that increasing participation in the Job-Hunting Skills module led to increasing Confidence Metrics – the points above did not fully account for the results we were seeing in 2020.

Why didn’t we see the same fall in Confidence Metrics that was seen in other government and national studies?

The team moved to exploring the concept of psychological resilience as a possible explanation.

Studies show that one of the factors leading to a person’s ability to demonstrate resilience is being able to make realistic plans, being able to follow those plans, having confidence in their strengths and abilities and demonstrating solid communication and problem-solving skills (Padesky & Mooney, 2012).

Building resilience for an individual means being prepared for challenges, crises and emergencies, and feeling like they have reliable contingencies in place to deal with unexpected future scenarios (de Terte & Stephens, 2014).

In other words, they are building self-efficacy beliefs, i.e. tying their strong beliefs to what they understand to be their capability level (Bandura, 1977).

The Job-Hunting Skills module makes an actionable process out of finding a job. It demystifies the steps involved and breaks down the process into bitesize pieces that build on previous knowledge.

It is taught as a cyclical and continuous process that each person works through repeatedly, gaining confidence with each iteration. At the end of the programme, the experienced worker comes away with a plan that is applicable across all job hunts, both now and in the future (i.e. it’s their reliable contingency).

We hypothesise that the feeling of self-efficacy gained from the module means that experienced workers believe they now have the improved abilities to deal with an ambiguous future.

We see their resilience and confidence in the future as an unanticipated “bonus effect” of the current Irish Government-funded reskilling programme, in which we bring together both job-hunting and technical skills.

Implications for Future Government Reskilling Programmes

We note that our findings on “bonus effects” are preliminary and that more research is needed to confirm that implementing job-hunting skills continues to offer these, as well as improving traditional success metrics across other circumstances.

To do so, testing its implementation within a different industry niche, a different age and experience group and a different geographical location would all be useful. For our own next steps, we plan on replicating this project in another country.

While job-hunting skills are typically low priority in large-scale reskilling initiatives, if these effects can be shown to be reliable, we believe they could form an essential part of being able to transition successfully into a new industry, alongside gaining the appropriate technical skills.

It is important to note that while the inclusion of a Job-Hunting Skills module will not result in a 100% job success rate, we found that the implementation of a mandated industry-specific component had the measurable impact of getting more people into jobs in their intended industry.

However, building a resilient workforce has benefits beyond “equipping them with knowledge” and “getting people into work.”

The traditional measurables of successfully completing a programme and/or getting a job, combined with the added “bonus effects” of the increased Confidence Metrics, could leave future reskilling efforts with a realistic opportunity to really go above and beyond.

In the private sector, this would be termed “delighting the customer.” And while it’s not necessarily a primary outcome measure for government programmes, it is an opportunity for an additional “successful outcome” as a result of the public spending involved in large-scale workforce reskilling.

As a private training provider, we acknowledge that we’re in a uniquely agile position to test and implement such initiatives that cannot necessarily be easily replicated by governments or traditional academia. Nonetheless, there are definitely opportunities for testing, and while it might not be easy, our findings suggest that the benefits might be worth pursuing.

Imagine a society where a population displayed an increase in the nine factors within our Confidence Metrics despite extreme circumstances such as a pandemic. This unanticipated benefit of “delighting the customer” suddenly becomes something to strive for, in the public and private sectors alike.

And if that is indeed the case, we ask if governments could make use of these observations to develop and implement their own programmes, in order to assess and capture the “bonus effects” – as well as traditional successes – when implementing reskilling initiatives in a post-COVID world.

References:

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological

Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Beckett, D. (2021, May 12). Coronavirus and the impact on output in the UK economy – Officefor National Statistics. Office for National Statistics.

Office for National Statistics. (2021, May 15). Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest insights – Office for

National Statistics.

Creaner, G. (2020, October 26). Working in Ireland’s Pharma/MedTech sector? It’s time to negotiate. GetReskilled. https://www.getreskilled.com/time-to-negotiate/.

de Terte, I., & Stephens, C. (2014). Psychological resilience of workers in high-risk

occupations. Stress and Health, 30(5), 353-355.

Department of the Taoiseach. (2020, September). COVID-19 resilience & recovery 2021: The

path ahead. Government of Ireland. https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/resilience-recovery-2020-2021-plan-for-living-with-covid-19/.

GetReskilled. (2021, May 26). List of 200 Pharmaceutical & Med Device factories by county in

Ireland. https://www.getreskilled.com/pharmaceutical-jobs/ireland-factory-table/.

Halligan, U. (Ed.). (2016). Future skills needs of the biopharma industry in Ireland. Expert

Group of Future Skills Needs. http://www.skillsireland.ie/all-publications/2016/biopharma-skills-report-final-web-version.pdf.

Higher Education Authority Ireland. (2021). HEA – Springboard+. Springboard+.

https://springboardcourses.ie/about.

IDA Ireland. (2021). Bio-Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology Ireland.

https://www.idaireland.com/doing-business-here/industry-sectors/bio-pharmaceuticals.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing

one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134.

Moore, C. (2007). Action mapping on one page. Training Design – Cathy Moore.

https://blog.cathy-moore.com/online-learning-conference-anti-handout/.

NIBRT. (2020). NIBRT annual report 2020 (B. O’Callaghan, Ed.). National Institute for

Bioprocessing Research and Training. https://www.nibrt.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NIBRT-Annual-Report-2020_final.pdf.

Padesky, C. A., & Mooney, K. A. (2012). Strengths-based cognitive-behavioural therapy: A

four-step model to build resilience. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19(4), 283-290.

Public Health England. (2021, May). COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report Week 20 (No. 20).

Higher Education Authority Ireland. (2016). Developing talent,

changing lives: An evaluation of Springboard+. Higher Education Authority Ireland. https://springboardcourses.ie/pdfs/An-Evaluation-of-Springboard+-2011-16.pdf.

Stringer, E. (2007). Action research in education (2nd Edition) (2nd ed.). Pearson.

[1] While there was no option for participants to indicate that a metric “stayed the same” (which we acknowledge as a limitation), they could skip any question they did not wish to answer. Future iterations of this survey will include a “stayed the same” option, to make this point more explicit.

Further Reading

This is part of a series of papers in the area of Career Coaching.

You might also be interested in: