Keeping Adult Learners Engaged in Distance Learning during Times of Crisis (INTED 2021)

Reflections on the decision making of experienced workers during COVID using the analytical lens of behavioural science

By Gerard Creaner, Sinead Creaner and Colm Creaner

Publication Date: March 2021

This paper was presented at the 15th Annual International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED) 2021

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read):

Abstract

This paper examines the experiences of a private training provider in keeping adult learners engaged in further study to secure their job position in pharmaceutical manufacturing companies, during the COVID-19 pandemic. It uses the analytical lens of behavioural science to better understand why these adult learners made the decisions they did with regards to engaging with further study.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing is a stable industry, independent of the recent economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This industry sector continued to hire personnel during national lockdowns, and so would be considered to be a very attractive employment opportunity during times of economic uncertainty for those looking to enter it. Likewise the idea of career progression and securing existing positions would be expected to be also highly attractive for those already within the industry.

In a post-COVID 19 world, Government expenditure will significantly outway income in order to restart the economy and get people back to work. As such it will be imperative that Government spending in the key area of reskilling and upskilling workers is implemented in the most effective manner possible, so that the Government can realise the full value of their reskilling investments. This paper gives insights into how experienced workers relate to Government-funded lifelong learning and reskilling initiatives.

The paper examines the findings of a case study of 350 experienced workers, who over 4-years successfully completed an academically accredited CPD Certificate (Continuous Professional Development), looking for career transition and progression in the secure Pharmaceutical manufacturing industry. This group of adult learners is of particular interest, as 60% of them have been a beneficiary of a Government-funded reskilling initiative.

This research will provide insights for Government training and education providers with reflections on best practice from one training providers’ experience, who has been delivering these programmes in an online distance learning manner over the last 10-years. The data set has been gathered over the 2017-2020 period across 350 experienced workers, coming from a variety of educational and employment backgrounds, with 5 to 25 years of work experience, all of whom successfully completed the same programme.

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

The analytical lens of behavioural science theories suggest some explanations for the decision making of these experienced workers with regards to their further study.

The key outcome of the paper are insights into the decision making of experienced workers, that can be implemented by Governments and education providers to get a more effective return on investment from the major training initiatives that will be a part of every country’s back to work programmes in a post-COVID world.

Introduction

Job security for many experienced workers all around the world has been undermined by the economic fallout, following the Government decisions that were made to control the COVID pandemic. In a world where increasingly there are no longer “jobs for life”, experienced workers need to find ways to regularly upskill themselves, so as to keep themselves current with their industry and to make themselves more secure in their roles.

Due to the turbulent nature of the world’s economies in 2020, the logical decision for experienced workers, who transitioned into the pharmaceutical industry relatively recently, would be to pursue a lifelong learning pathway that would lead to a more secure and possibly higher-paying role, in this stable and secure industry, free from the cyclical ups and downs of the economy. Signing up for the follow-on programme to the initial one that allowed these workers to get a job in this industry, would also lead to further qualifications, and would bring valuable technical (Validation) skills in-house for a company. This would further enhance the worker’s value to the company, leading to more job security for the worker. It would be expected that the majority of the experienced workers, having already realised benefits from completing the previous programme, would choose to sign-up for the next programme and continue along the path to lifelong learning.

Following the COVID pandemic and the need for Governments to engage in reskilling back-to-work programmes to kick start their economies, research into online lifelong learning has never been more relevant.

This paper takes the experiences of a private training provider in reskilling experienced workers for new jobs and careers in the high tech pharmaceutical manufacturing industry. It uses the data and insights generated to provide a unique perspective on the key elements of lifelong learning with relevant technical programmes to help experienced workers find jobs and build new careers in a new industry sector.

The data set has been gathered over a four-year period (2017/18/19/20) from 350 experienced workers, with 5 to 25 years of work experience, all of whom successfully completed the same initial programme to gain entry into the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. Approximately 60% of this group were beneficiaries of Government reskilling initiatives for the workforce.

Conceptual Framework

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

In Bereday’s model, ‘everyday’ comparability is distinguished from socially-scientific or laboratory methods. The everyday comparability approach fits with individualistic practitioner research in that it favours establishing relations between observable facts, noting similarities and graded differences, drawing out universal observations and criteria, and ranking them in terms of similarities and differences.

In everyday comparability, the view is subjectively from within and deliberately without perspectives detached. It focuses on group interests, social tensions, impact factors and collective beliefs, patterns, and behaviours as experienced by the authors.

In terms of analytical steps, this paper uses Bereday’s four stages as illustrated by Jones (Jones, 1971), as follows:

- Stage 1: Description of each case using a common approach to present fact

- Stage 2: Interpretation of the facts in each case using knowledge other than the authors

- Stage 3: Juxtaposition for preliminary comparison using a set of relevant criteria

- Stage 4: Simultaneous comparison, emergence of conclusions and hypotheses

The perspective in this paper is the authors’ own as the private training provider of vocational education programmes, mindful of the particular risks of insider research (Rooney, 2005).

Previous Research

Previous research from this private training provider was reported at the Research Work Learning Conference 2015 in Singapore. This research explored the building of a knowledge based economy through lifelong learning, and one of its key conclusions was the insight that while theory and government strategies support the building of a knowledge-based economy through the lifelong technical learning of its citizens, it appeared that employees did not want to invest their time and effort in lifelong learning once a job is secured.

This research was then built upon at the ICDE World Conference on Online Learning 2019 and the IMSCI Conference 2020, where studies were undertaken to understand the decision making processes of experienced workers, as to why an experienced worker decided to finish a course versus finding a job, and what impact career coaching had on the workers outlooks concerning job security, career advancement and their desire to achieve mastery in their chosen field.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework in which this case study was analysed is the field of Behavioural Science.

Behavioural Science is the study of human motivation, decision making, and actions. It tries to understand how people interpret information; why they make the decisions they do when faced with multiple options; and, ultimately, why people behave the way they do. The aim of the field of behavioural science is to understand and apply the “human factor” to the decision-making process, rather than building theories on people making simple rational/logical decisions and choices, i.e. the theoretical concept of the logical/rational “Economic Man”.

As a species, humans have evolved a strategy of decision making, that uses mental shortcuts (called heuristics), to allow subconscious decision making.

Colloquially these heuristics are called “rules of thumb”. Daniel Kahneman describes this process as basically trading a difficult question, for an easier one within our brains. While there is an evolutionary advantage for using these rules of thumb in the increasingly complex world in which we live, they can lead to cognitive biases.

A cognitive bias is a systematic error in thinking. In other words, the decision that arose was due to an error in how information was processed due to an inherent reliance on our innate heuristic.

Herbert Simon is seen as the founder of modern behavioral science, after winning the Noble Prize for Economics in 1978 for his theory of Bounded Rationality. He demonstrated that humans make decisions to achieve a satisfactory outcome, rather than an optimal one because our decisions are made based on the knowledge we have, our ability to process this knowledge, and the amount of time we have to make the decision (Simon, 1955). This suggests that experienced workers’ abilities to implement the knowledge they receive on career progression and lifelong learning is dependent on these three factors.

Overview of Case Study

The group of experienced workers around whom this research is based comprises of 350 experienced workers, coming from a variety of educational and employment backgrounds, with 5 to 25 years of work experience, all of whom successfully completed the same initial programme over a 4-year period (2017-2020).

Approximately 60% of this group were beneficiaries of Government reskilling initiatives for the workforce. This group of 350 were divided into 6-sub groups, based on whether they self-funded the programme themselves or received Government funding to do it, and which year they completed the programme (2017/18/19/20).

Each sub-group received an individualised outreach email campaign which had the same behavioural science themes delivered in a format relevant to their programme funding and year of completion:

- Group 1: were part of a Government reskilling initiative which paid either 90% or 100% of their course fees. This group had by this point finished their original programme in 2017/2018, and had accumulated between 6 and 24 months work experience. 60% of them had found a job within 3-months of graduating. None of them had sought out further opportunities for lifelong learning, or had made the decision to maximise on the investment provided by Government to pursue a degree qualification

- Group 2: were part of a Government reskilling initiative which paid either 90% or 100% of their course fees. This group had by this point finished their original programme in 2019, and had accumulated between 6 and 12 months work experience. 60% of them had found a job within 3-months of graduating. None of them had sought out further opportunities for lifelong learning, or had made the decision to maximise on the investment provided by Government to pursue a degree qualification

- Group 3: were part of a Government reskilling initiative which paid either 90% or 100% of their course fees. This group had been impacted by the national lockdown procedures due to the COVID pandemic in 2020, and were still waiting to complete the lab practical element of their studies (because of social distancing requirements). They had completed all other components and were in a holding pattern until lockdown measures were lifted.

- Group 4: This group had invested in themselves by self-funding to complete their original programme. They finished their original programme in 2017/2018, and had accumulated between 6 and 24 months work experience. None of them had sought out further opportunities for lifelong learning, or had made the decision to maximise on the significant monetary investment they had placed in themselves to pursue a degree qualification

- Group 5: This group had invested in themselves by self-funding to complete their original programme. They finished their original programme in 2019, and had accumulated between 6 and 12 months work experience. None of them had sought out further opportunities for lifelong learning, or had made the decision to maximise on the significant monetary investment they had placed in themselves to pursue a degree qualification

- Group 6: This group had invested in themselves by self-funding to complete their original programme. This group had been impacted by the national lockdown procedures due to the COVID pandemic in 2020, and were still waiting to complete the lab practical element of their studies (because of social distancing requirements). They had completed all other components and were in a holding pattern until lockdown measures were lifted.

There were 5 components to the outreach which were all aimed at encouraging the experienced workers to continue on their pathway to a BSc degree for career progression, and to give them further Job Security in the uncertain times the workers found themselves.

Each of the components were underpinned with key behavioural science theories which were aligned to the workers innate heuristics, and minimised cognitive biases, taking particular note of to work with the theory of Bounded Rationality rather than against it.

The 5 components were:

- A Warm-Up Outreach – this included giving the group access to a series of articles on the salaries they could earn through completing this programme, what key skills they would need for this job, what their day to day tasks would be, and where the programme would fit into their bigger long term career goals. This was served to them through Facebook.

- Initial Expression of Interest – each person in the group was then contacted directly via an 8-email campaign, giving details on why this would be a good move for them, and paying particular attention to the key heuristics and biases of loss aversion, diversification, Dunning-Kruger and regret aversion. At the end of this email campaign, each person in the group was asked to click a button to show they were interested in learning more about this opportunity, or not.

- A one-on-one phone call with a member of the team – each person of the sub-group who had clicked they were interested in learning more (and those who did not perform either action requested as part of component 2), had one-on-one phone calls with a member of the team. This call was aimed at minimizing ambiguity aversion and inertia, reinforcing the social norm of this decision, and working with a person’s dual-self model.

- A follow up post the phone call – those who received a phone call, were subsequently emailed with personalised information on how they could sign-up for the course, and start taking the next step in their careers. This was focused on minimizing choice overload and myopic procrastination.

- A reminder that the deadline to take the step was closing – as the final component of the outreach, the group who had received a phone call, were then advised that the window of opportunity for taking this course was closing fast, aimed at overcoming the worker’s innate inertia and regret aversion.

Due to the turbulent nature of the world’s economies in 2020, the logical decision for experienced workers, who transitioned into the pharmaceutical industry relatively recently, would be to pursue a lifelong learning pathway that would lead to a more secure and possibly higher-paying role, in this stable and secure industry, free from the cyclical ups and downs of the economy.

Signing up for the follow-on programme to the initial one that allowed these workers to get a job in this industry, would also lead to further qualifications, and would bring valuable technical (Validation) skills in-house for a company.

This would further enhance the worker’s value to the company, leading to more job security for the worker. It would be expected that the majority of the experienced workers, having already realised benefits from completing the previous programme, would choose to sign-up for the next programme and continue along the path to lifelong learning

Research Findings

The data gathered for this paper is quantitative. The limitations of quantitative studies – as potentially statistically relevant due to large data sets while being humanly irrelevant, missing the contextual details surrounding the results – are acknowledged. However, in this case, in the straddling between insider-actor mode and outsider-observer mode (Robson, 2011), and due to the research question in hand, the research generated provides a large enough basis on which to build observations.

The data for this paper was gathered directly by the training provider covering student completion and progression rates, as well as email open rates from outreach campaigns. The data has been processed for ease of reading into bar graphs.

As part of this study, the decision making of both students who had received Government funding to reskill, and those who have self-funded were examined.

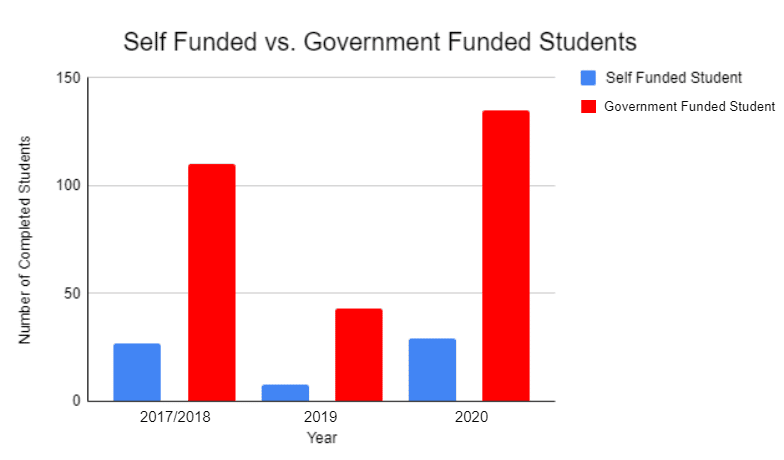

Figure 1, shows the difference in the number of students who successfully completed the original programme from Government funded initiatives as opposed to self funding.

Figure 1:(Graph Showing the Number of People who successfully completed the course from 2017-2020 through government funding or self funding)

The key points to observe from Figure 1 are the overall numbers of students that completed the original programme. From this figure, it can be seen that the total number of Government funded students on this course is 288, whilst the number of self funding students is 64. While there is a significant difference in these two group sizes, the relevancy of the self funders is still maintained due to the fact that it creates just under 20% of the overall size.

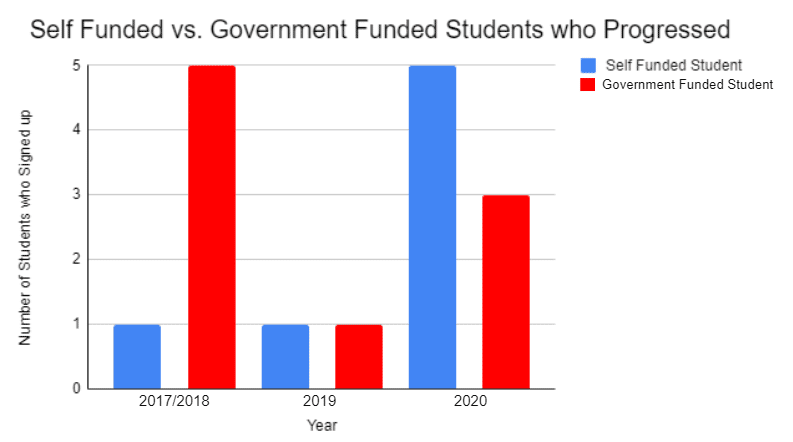

Once the size of the two difference audiences who had successfully completed the programme was determined, the data was analysed to see how many students in each of the audiences progressed to the next programme following successful completion of the initial programme from which they secured a job in the industry. This is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: (Graph Showing the number of people who progressed on from the course after receiving government funding or self funding the first course)

Figure 2 demonstrates the significance of the self funded student pool as it is responsible for an equivalent number of students who progressed onto the second course, despite being only 20% of the audience size of the Government funded students.

However, Figure 1 and Figure 2 demonstrate empirically that irregardless of whether the student is self funded or received Government funding, very few students moved onto the next programme, despite successfully completing their inital programme.

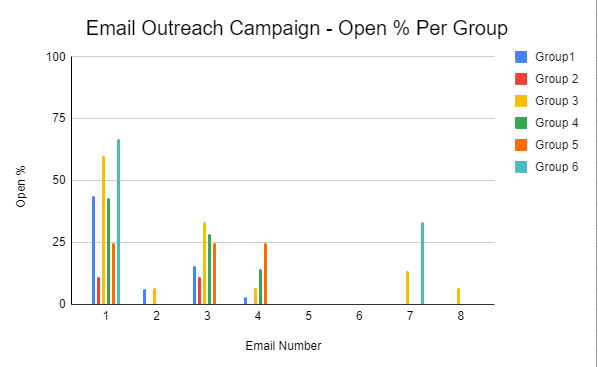

This insight led to a detailed examination of how each of the groups outlined in Section 5 interacted with the Outreach Campaign. Figure 3, shows the effectiveness of the email outreach campaign to each of the individual groups.

Figure 3: (Graph showing the percentage open rates of emails that we sent them during the 1 month long email outreach campaign)

Figure 3 above demonstrates that there was a significant amount of interest from all groups in this study with the 1st email. This interest dropped off significantly for the 2nd email, however was due to the fact that this email was only sent to the small number who did not interact with the first email.

The strong response continued through emails 3 and 4 demonstrating that the experienced workers remained interested in campaigns up to a point. However, this interest is at best half of the overall student intrigue demonstrated in email 1. There was a 0% open rate on emails 5 and 6, with little interest being demonstrated in emails 7 and 8.

The data shows that the expectation that the majority of the experienced workers, having already realised benefits from completing the previous programme, would choose to sign-up for the next programme and continue along the path to lifelong learning, was incorrect. Figures 1, 2, and 3 demonstrate that there are key underlying decision making processes that interfere with what should be a straightforward and logical decision.

This leads us to the main research question of this paper, “How can the analytical lens of behavioural science theory inform the structures and incentives for lifelong learning, so as to engage with the heuristics and cognitive biases of experienced workers, and influence their decision making beyond the initial point of when the new job is secured?”

Analysis and Discussion

This research found the lens of Behavioural Science to be particularly useful to interpret the decisions of experienced workers in an online environment.

This research question can be broken down into three parts:

- Why were all these 350 experienced workers willing to complete the original programme to get a job in the pharmaceutical industry?

- Why within a relatively short period of time, was only 1-in-20 of the same group willing to take the next programme, which would further secure their role in the industry and/or prepare them for career progression?

- What heuristics and cognitive biases inform the decision making of experienced workers beyond the initial point of when the new job is secured?

A simultaneous comparison is now conducted for the emergence of conclusions and hypotheses in tabular form below (Stage 4 Bereday). Table 1 (below) shows the analytical lens of behavioural science, laid over each part of the research question.

| Behavioural Science Theory | Definition | Relevance to the question |

|---|---|---|

| Why were all these 350 experienced workers willing to complete the original programme to get a job in the pharmaceutical industry? | ||

| Take-the-best (Heuristic) | A decision maker will base the choice on one attribute that is perceived to discriminate most effectively between the options. The decision maker will instinctively look for the “best option” using this one attribute (Gigerenzer & Goldstein, 1996). | When the experienced worker came to the programme they were either unemployed and looking for a job, or they were dissatisfied with their current job situation. The “good” reason for making the decision to engage with reskilling programmes was to change their current situation and thus negate their current dissatisfaction. This programme offered them a simple choice - either potentially change their current situation (take the course) or stay the same (don’t take the course). |

| Satisficing | People tend to make decisions by satisficing rather than optimizing (Simon, 1956) | When considering the experienced workers, the decision made to take the original programme was a satisficing decision. The original programme satisfied the requirements of their situation to change career or get a new job. The decision worked within the principles of bounded rationality. Optimising would mean taking advantage of the investment (either by the individual or by the Government) to pursue their degree, however, this works outside the parameters of the satisficing decision making process and so was not the decision made by the experienced worker. |

| Why within a relatively short period of time was only 1-in-20 of the same group willing to take the next programme, which would further secure their role in the industry and/or prepare them for career progression? | ||

| Social norms | This is the tendency to follow what is perceived as the appropriate behaviour based on the rules within a group of people (Dolan et al., 2010). | Social norms dictate that when you are unemployed or dissatisfied with your job, you look for a new job (or upskill before looking for a new job). Once the experienced worker moved into a new job, the social norm that was previously adhered to changed. In this new environment, it is not a social norm of their co- workers to engage in upskilling programmes (outside of in-house training). Only those looking for leadership roles (or those looking to leave to go to a new company), go outside the company to gain new qualifications. The social norms in this environment therefore is not to consider further lifelong learning opportunities unless looking to become a leader. |

| Default (option) | This is the set course of action that will happen. Default options are very effective nudges to normalise behaviour (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) | When the worker was unemployed or dissatisfied with their current situation, the default option is to remedy the situation. Once the experienced worker has secured the job or their situation is more satisfactory, the default option changes to continuing on as normal. Engaging in lifelong learning for the purposes of changing job or advancing a career, goes against this default option and therefore worked as a nudge to keep the experienced worker from engaging with further lifelong learning. |

| What heuristics and cognitive biases inform the decision making of experienced workers beyond the initial point of when the new job is secured? | ||

| Inertia | This is when things stay the same due to a person’s inaction (Madrian & Shea 2001). Nudges can work with people’s innate inertia or against it (Jung, 2019). | When the worker was unemployed or dissatisfied with their situation, it was easy for the worker to overcome their innate inertia to change their situation. However, once the job was secured or the workers' feelings of dissatisfaction changed, there was not the drive to overcome inertia any more. To engage in lifelong learning, there is a line of demarcation that the experienced worker must cross from satisfactory to unsatisfactory, and only once crossed, will the worker be able to overcome inertia for change. |

| Decision Fatigue | Decision Fatigue occurs after long periods of decision making which require huge effort and self-regulation. Decision Fatigue can lead to to poor choices and self-regulation (Vohs et al., 2008) | When the worker was unemployed or dissatisfied with their situation, the primary decision they focused on was how to change their current situation. Once they were engaged with the original programme, they were then forced into a series of just as monumental decisions surrounding studying, hunting for a job, and the impact on all this on their personal lives. This involved long periods of self-regulation, control and self-discipline. Once they had secured the job and/or finished the programme, their decision making marathon came to an end. The experienced worker can suffer from decision fatigue at this point - and this can result in one of two actions, either a conscious refusal to put themselves back into this “change to their current situation” again or the worker had not sufficiently recovered from their decision fatigue to make the decision which would require lots of self-regulation, control and self-discipline once again. In order to be ready to engage with lifelong learning again, the experienced worker must have sufficiently recovered from their decision fatigue. |

Conclusion

This paper examines the decision making of experienced workers as it relates to lifelong learning, beyond the initial point of when they have secured a new job.

The case study found that of the 350 experienced workers who completed an initial programme to get a job in the pharmaceutical industry, only 1-in-20 of them (within a relatively short period of time) were willing to take the next follow-on programme, which would secure their role in the industry and/or prepare them for career progression.

Looking at this through the lens of Behavioural Science, the cognitive biases of Inertia and Decision Fatigue gives possible insights into this apparently “irrational” decision making by these experienced workers.

This paper has potential benefits for Governments engaged in kick-starting their economies, as expenditure will be significant to get people back to work. Best practice for incorporating these lifelong learning initiatives for reskilling workers will significantly increase the return on investment of taxpayers monies. As well this, Governments will realise additional benefits in creating a workforce that is more disposed to engaging with future back-to-work initiatives when the need arises.

In conclusion, this paper is of particular relevance at the current time as the world enters 2021 and a post-COVID world will require more reskilling initiatives to be completed, and adding a behavioural science insight to lifelong learning initiatives has never been more important.

Conference Presentation

These findings have been presented at both the INTED 2021 Conference in Spain and the BEST 2021 Conference in Australia. The recordings can be viewed below:

References

[1] Creaner, Gerard (2015) ‘The Challenge of Delivering CPD Training for the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico within differing policies for a Knowledge Based Economy’ , RWL 9 Conference on Research Work Learning, Singapore, 2015 Volume 1, Part 3, pg 1171 – 1191

[2] Creaner, Gerard (2019) ‘Harnessing the Potential of Online Learning to Build Effective & Sustainable Lifelong Learning

Frameworks: Case Studies from Ireland and Singapore’, ICDE World Conference on Online Learning, Ireland, 2019, Volume 1, Part 1, pg 128-145

[3] Halpern, David. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How small changes can make a big difference. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

[4] Jones, P.E (1971). Comparative Education: Purpose and Method. University of Queensland Press: St. Lucia, Queensland

[5] Robson, Colin (2011). Real World Research 3rd Edition. Wiley: United Kingdom

[6] Rooney, Pauline (2005) ‘Researching from the Inside – Does it Compromise Validity’, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2005, Dublin

[7] Shields, Patricia; Rangarajan, Nanhini (2013). A Playbook for Research Methods: Integrating Conceptual Frameworks and Project Management. New Forums Press: United States of America

[8] Simon, Herbert (1955) ‘ A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1955, Volume 69, Pg 98-118

[9] Thaler, Richard H & Sunstein, Cass R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press: United States of America

[10] Thaler, Richard H. (2015) Misbehaving: The making of Behavioural Economics. W. W. Norton & Company: United States of America

Further Reading

This is part of a series of papers in the area of Lifelong Learning.

You might also be interested in: