An Effective Online Framework for Lifelong Learning (WCOL 2019)

By Gerard Creaner

Publication Date: November 2019

This paper was presented at the World Conference in Online Learning (WCOL) 2019

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read):

Abstract

This paper examines one private training provider’s experience building an effective online framework for lifelong learning.

With a focus on delivering training for the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry, and using the

analytical lens of behavioural economics, it draws on this experience to model the development of a mature workforce over a seven-year case study (2012-2019), across two locations (Ireland and Singapore), involving 2,000 workers.

Contextual data for the paper were drawn from relevant economic policy and employment literature for each case study location, from relevant pharmaceutical sector publications, and from original training documentation generated during the seven-year case study.

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The perspective is reflective, rational enquiry with the aim of better understanding the successes achieved for replication in the future. The case study data are presented and analysed using Bereday’s four stages in both methodology and structure: description, interpretation, juxtaposition, and comparison, augmented with a fifth initial stage ‘intuition’ as suggested by Cirigliano (Cirigliano,1996).

The study aims to better understand the underlying motivations and drivers of experienced workers who wished to make a mid-career change. This is achieved by testing the effectiveness of the training provider’s established framework for online programme delivery and analysing participant feedback.

Insights into current programme effectiveness as well as areas for improvement lay out a process that could be implemented across a range of next-generation, high-tech industries, in many countries.

The conclusions are based on interpretation of the data using the analytical lens of behavioural

economics, and offer insights into how governments might harness the potential of online lifelong learning for experienced workforces, to transform lives and societies.

Key findings include:

- Proof of the robustness of the previously developed Sourcing, Education & Career Coaching (SEC) framework.

- Successful outcomes (completing the programme and/or finding a job) were independent of the individual’s years of work experience or highest previous academic qualification.

- Satisfaction rates with the programme screening and delivery were generally higher than the number of students who had a successful outcome from the programme at the time of survey. It appears that many currently unsuccessful participants remained optimistic about their future potential and, therefore, provide an engaged cohort for further intervention.

- Nudge Theory (from the field of behavioural economics) could provide insights to increase the percentage of students with initial successful outcomes, as well as ways to further develop currently unsuccessful participants.

Key Words: Online Learning Initiative, Lifelong Learning, Behavioural Economics, Prospect Theory, Loss Aversion, Nudge Theory

Introduction

This paper aims to examine the success of a current online framework for lifelong learning, and consider areas for further development. The private training provider in question reskills experienced workers from other industries to meet the skills shortages currently being experienced in both Ireland and Singapore’s pharmaceutical manufacturing industries.

The pharmaceutical manufacturing industry is a key pillar of the Irish economy (17% of GDP, 45% of exports, $50 Billion Capital Asset Replacement Value, and employing 50,000 workers)(IDA, 2015). Likewise, in Singapore, it is the fourth pillar of their economy (5% of GDP, $15 Billion Capital Asset Replacement Value, and employing 6,000 workers)(EDB, 2019).

The opportunities that pharmaceutical manufacturing industry growth and ongoing investment brings to both Ireland and Singapore are numerous, and include:

- Employment – one of the most obvious opportunities this level of investment brings is well-paid locally-based jobs.

- Development of an industrial “cluster” – as pharmaceutical companies expand their operations, the number and range of specialist supporting companies who offer services to the industry will increase.

- Specialised workforce – the presence of specialised manufacturing sites means the workforce develops to reflect that need through flexible vocational education programmes.

- Financial – at a Government level, strong high-tech industries are needed for a strong economy. At an individual level, these local jobs are well-paid, stable, and secure.

Over the past seven-years, this private training provider’s vocational education (VE) programmes have been delivered to experienced workers with five to twenty-five years’ work experience, who are returning to employment or changing their career. They are particularly focused on individuals appropriate for operator and quality technician roles in the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry, since this is where significant skills gaps occur when the industry expands in a given location. These online programmes also provide a pathway to academic accreditation at Bachelor degree level.

The key objectives of this online VE are:

- To help governments and industry build local talent pools of operator and quality technicians

- To support the expanding pharmaceutical manufacturing industry

- To utilise online VE to teach the quality systems necessary to consistently manufacture safe and effective medicines for patients

- To give individuals the knowledge and skills needed to make a successful career change into the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry

This paper will focus on three different groups across two locations – unemployed workers in Ireland, employed workers in Ireland, and employed workers in Singapore. It aims to objectively measure the success of the current Sourcing, Education & Career Coaching (SEC) framework and identify areas for further improvement.

Insights into current programme effectiveness as well as areas for improvement will lay out a process that could also be implemented across a range of next generation, high-tech industries, in many countries.

Background and Previous Research

The private training provider has developed VE programmes that are academically accredited as Continuous Professional Development (CPD) certificates leading to a BSc degree in the Manufacture of Medicinal Products (Level 7). Programmes have been validated, approved, and accredited for an online delivery format. Curriculum development is rooted in delivering career-focused VE to meet specific industry sector requirements.

Previous work in this area was reported by the author at the Research Work Learning Conference 2015 in Singapore. The main finding from that work was that while current theory and Government strategies support the building of a knowledge-based economy through lifelong learning of its workers, it appears that neither employers nor workers want to invest their time and effort once the resource is hired or the job is secured (Creaner, 2015). That paper also raised the question of whether a nation can develop a knowledge-based economy without the emotional support of its citizens and employers for lifelong learning. (Creaner, 2015)

This study further builds on the conclusions of that paper, and aims to uncover more insight into the drivers and motivations of experienced workers using VE to facilitate a mid-career change.

Previous data gathering, research, and analysis of student statistics and feedback to the training provider has led to the development of a three-stage process – the SEC framework – Sourcing, Education, Career Coaching.

Sourcing:

Sourcing and screening of candidates is the process by which the training provider assesses whether a candidate is a good fit for the programme and for a career in the industry.

Rather than selecting candidates exclusively on their previous academic achievement, each candidate is assessed for their overall suitability for a career in the industry, with a focus on their transferable skills gained across a wide range of work experience. To help establish this, a phone call is conducted with every candidate prior to their acceptance onto the programme. This rigorous screening process results in only 300 people (6%) of the 5,000 initial applicants being accepted every year. This combination of sourcing and screening is a key component to having only the most suitable candidates being enrolled.

Education:

This is the part of the SEC process where the technical modules are delivered in a virtual environment. The modules utilise a variety of learning methods including short videos, lecture notes, self-assessment quizzes, and reflective questions each week to deliver the technical knowledge needed for working in this highly-regulated industry.

This is accompanied by regular weekly contact from a course coordinator (i.e. pastoral support) to maintain accountability and motivation by the student to progress through the course.

Career Coaching:

In response to feedback from previous students, an online career coaching module was added.

Since these students are experienced workers looking to make a mid-career change, some are apprehensive about how easily they’ll be able to find a job in a new industry and others are overly confident. This module has been designed to normalise those different mindsets and it includes a step-by-step process for navigating the complex path to finding a job in a new industry. The end of module assignment is a simulation of a job application (using a real job advert) and each student is given specific feedback on areas for improvement in future job applications.

When this was first introduced (as an elective module), less than 25% of students chose to take it. After proving its effectiveness, it has now become a mandatory component of the overall mid-career change programme. It was observed that a significant proportion of students display the Dunning-Kruger Effect (where they believe their abilities in a particular area are greater than they actually are) (Kruger & Dunning, 1999) and they believe, as experienced workers, that they already possess the necessary job hunting skills to secure a new job. Many are shocked by the amount of information they were previously unaware of and, as a result, students are overwhelmingly positive about the module’s content.

Using the SEC framework, a robust system for finding and training local workers has now been established. This study is aimed to objectively assess the success of this framework before going on to look at areas for further improvement.

Conceptual framework

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison of the three case study groups draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

In Bereday’s model, ‘everyday’ comparability is distinguished from socially-scientific or laboratory methods. The everyday comparability approach fits with individualistic practitioner research in that it favours establishing relations between observable facts, noting similarities and graded differences, drawing out universal observations and criteria, and ranking them in terms of similarities and differences.

In everyday comparability, the view is subjectively from within and deliberately without perspectives detachment. It focuses on group interests, social tensions, impact factors and collective beliefs, patterns, and behaviours as experienced by the author.

In terms of analytical steps, this paper uses Bereday’s four stages as illustrated by Jones (Jones, 1971), as follows:

- Stage 1: Description of each case using a common approach to present facts

- Stage 2: Interpretation of the facts in each case using knowledge other than the author’s

- Stage 3: Juxtaposition for preliminary comparison using a set of relevant criteria

- Stage 4: Simultaneous comparison, emergence of conclusions and hypotheses

The perspective in this paper is the author’s own as the private training provider of vocational education programmes in the two case study locations, mindful of the particular risks of insider research (Rooney, 2005).

Research Method

As part of the validation and quality system metrics for this academically accredited programme, the training provider carries out an annual survey of students.

The data gathered for this paper are quantitative. The limitations of quantitative studies – as potentially statistically relevant due to large data sets while being humanly irrelevant, missing the contextual details surrounding the results – are acknowledged. However, in this case, in the straddling between insideractor mode and outsider-observer mode (Robson, 2011), and due to the research question in hand, the research generated provides a large enough basis on which to build observations.

This is a descriptive study where the subjects are only measured once after course completion. The training provider surveys an average of 200 students per year, out of a total student population of 300 students.

Students answer 60 questions across five different categories to establish a full profile of the answers in relation to each other and in relation to other students, past and present. The five categories are:

- Employment status update

- Application screening process feedback

- VE programme feedback

- Career coaching programme feedback

- Recommendations for future improvements to the programme (this section provides some qualitative data through open-ended written responses)

The following demographic data are also gathered from each respondent:

- Age (using 5-year bands through 24-50 age range)

- Highest previous qualification (Levels 5-9)

- Exam results for each module

- Employment outcome

The data for this paper were gathered directly by the training provider using tools including Survey Monkey and Typeform. The data has been processed for ease of reading using Microsoft Excel. For data organization, interpretation, analysis and presentation, the total answers have been processed into descriptive statistics (i.e. summary statistics broken down answer-by-answer, year-by-year).

Results of Research

Data analysis began by looking at student “satisfaction” surrounding the full SEC process (i.e. screening process, the delivery of the online study materials, and technical support during the programme).

| Metric Measured | 2017 % Agree | 2018 % Agree |

|---|---|---|

| The application screening process was good | 94% | 94% |

| Benefited from being able to complete the programme from home | 91% | 92% |

| Information was clearly presented in the programme | 90% | 91% |

| The final assignment requirements were clearly understood | 89% | 90% |

| Understood what the course would involve before starting it | 88% | 88% |

| There was a good support network when they were in trouble | 83% | 84% |

| Overall training was beneficial | 83% | 84% |

Table 1. Analysing key metrics surrounding student’s satisfaction with the programme delivery, pastoral, and academic and technical support for the 2017 and 2018 student years.

When asked about their attitudes and outlooks on lifelong learning, career advancement, and future job security, the following data resulted:

| Metric Measured | 2017 % Agree | 2018 % Agree |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation for getting a rewarding career had increased | 84% | 95% |

| Ambition to get a better-paid job had increased | 86% | 95% |

| Determination to succeed had increased | 87% | 94% |

| Ambition for career advancement had increased | 84% | 93% |

| Confidence in the future had increased | 78% | 92% |

| Confidence in their future job security had increased | 75% | 89% |

| Engagement with life-long learning had increased | 82% | 86% |

| Enjoyment of further study had increased | 76% | 85% |

| Ambition to achieve mastery in their chosen career had increased | 78% | 83% |

Table 2. Analysing key metrics surrounding student’s attitudes to lifelong learning, career advancement, and future job security for the 2017 and 2018 student years.

The number of experienced workers who had a successful outcome, defined as completion of the programme and/or getting a job by the time of survey, is noted in Table 3 below. This confirms the high percentages of successful outcomes for 2017 and 2018 (82% and 76% respectively) and the robustness of the online SEC framework for lifelong learning.

| Metric Measured | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Total: | 304 | 318 |

| Successful Outcome (Total): | 251 (82%) | 243 (76%) |

| Number who completed and got a job: | 101 (33%) | 102 (32%) |

| Number who completed but didn’t get a job by the time of survey: | 81 (26%) | 75 (23%) |

| Number who got a job but didn’t complete: | 69 (22%) | 66 (20%) |

| Unsuccessful Outcome: | ||

| Number without either successful outcome: | 53 (17%) | 75 (24%) |

Table 3. Comparison of 2017 and 2018 looking at students and their outcomes in the case study of “Unemployed Workers in Ireland”.

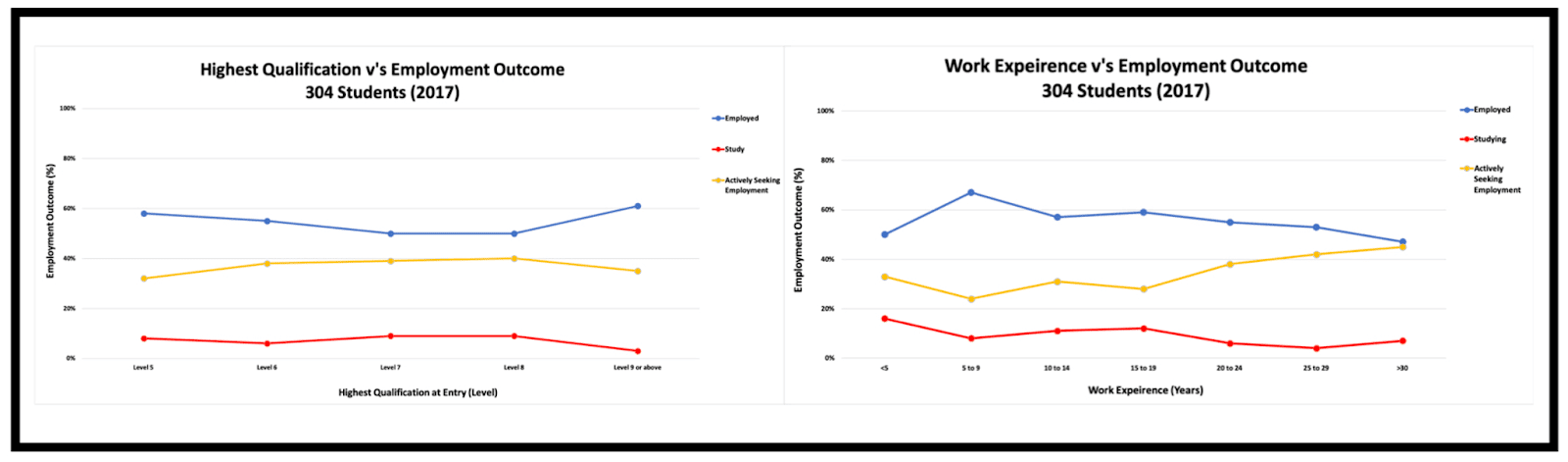

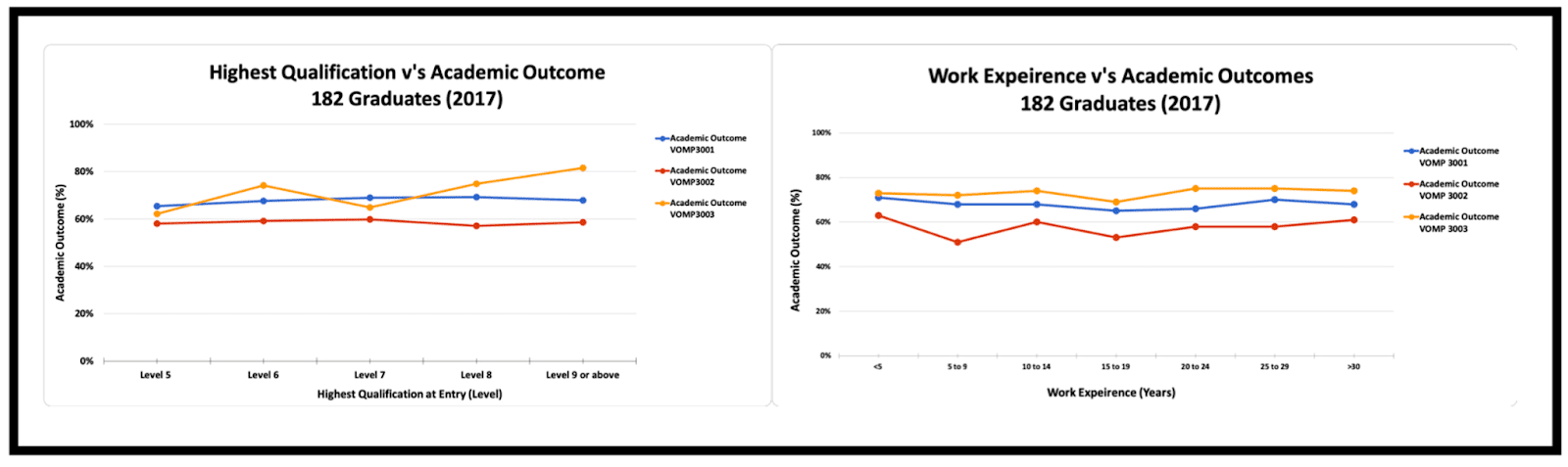

An analysis of the survey feedback data indicated that successful completion of the VE programme and finding a job were independent of a student’s years of work experience or their previous highest academic qualification.

Figure 1. Analysis of “Employment Outcome (%)” as it relates to “Work Experience (Years)” and “Highest Qualification at Entry (Level)”

Figure 2. Analysis of “Academic Outcome (%)” as it relates to “Work Experience (Years)” and “Highest Qualification at Entry (Level)”

Bereday (Bereday, 1964) suggests that setting cases out in juxtaposition using criteria or variables that emerge naturally from the data, will identify areas of convergence and areas of difference. Following this process, the variables and findings are presented in Table 4.

| Variable | Unemployed Workers Ireland | Employed Workers Ireland | Employed Workers Singapore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Audience | 950 survey responses | 20 survey responses | 150 survey responses |

| Nature of Survey | Looks at the 5 areas outlined in the Research Methods section | Looks at the 5 areas outlined in the Research Methods section | Only measures traditional academic validation and quality systems metrics |

| Academic Qualification of the Programme | Level 7 academically accredited CPD Certificate | Level 7 academically accredited CPD Certificate | Singapore WSQ (Workforce Skills Qualification) Certificate |

| Completed the programme | 55% of students completed the programme | 74% of students completed the programme | 75% of students completed the programme |

| Found Employment by the time the survey was taken | 54% of students found a job after the programme (more than half of these found employment whilst still studying on the programme) | 70% of people were in employment when the programme started. Only 40% of students are actively looking for a job in Pharmaceutical manufacturing after completing the course | This metric was not measured as part of the survey |

| Satisfaction of students | This analysis shows that more students were generally satisfied with the programme, than had a successful outcome from it. i.e some students were happy even though they didn’t complete the programme or get a job. | 100% of respondents believed that overall the training was beneficial to them even though only 70% completed the programme and only 40% of them were actively looking for a job at the time of the survey. | >80% of people reported at least 1 form of positive metric about the programme. 94% of students agree that overall the programme was beneficial to them. |

Table 4. Cross-comparison of variables across the three case study groups (in the two locations) including sample size, qualification, % completion, % employment, % satisfaction.

The processed data has surfaced three main questions:

- Why did some people complete the programme and others did not (when all were capable of doing so)?

- Why did some people get a job and make a mid-career change during/after the programme and others did not (when all were capable of doing so)?

- Why are people equally happy with the programme irrespective of whether they have had a successful outcome from it or not?

Theoretical Framework for Analysis

In order to answer these questions and better understand the reasons why a number of students did not achieve a successful outcome (and with a view to increasing that percentage), a discussion in the area of human decision making was explored, focusing on the field of behavioural economics.

The aim of the field of behavioural economics is to understand and apply the “human factor” to the decision-making process in economics, unlike classical economists who construct their theories on people making simple rational/logical decisions and choices (i.e. the theoretical concept of the logical/rational “Economic Man”).

The analytical lens of behavioural economics in understanding the “how” and “why” of human factors in decision making, and in particular Bounded Rationality, Prospect Theory, Nudge Theory and the Dual System Planner-Doer model to interpret the data about successful outcomes for this group, will lend insight into building a sustainable and effective online framework for lifelong learning.

Bounded Rationality:

The founder of modern behavioural economics was Herbert A. Simon, who won the Noble Prize for Economics in 1978 for this theory of Bounded Rationality. He suggests that humans are satisficers and not optimisers i.e humans are bound by three things when making a decision:

- Amount of information available

- Their cognitive limitations

- The amount of time they have

Herbert Simon’s work was further built upon by Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler, both of whom also won the Noble Prize in Economics (2002 and 2017 respectively) for their contributions to this field.

Prospect Theory:

Prospect Theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979 after completing detailed research to explain how people make decisions that involve risk and uncertainty. This resulted in developing models to explain Loss Aversion and the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

Loss Aversion:

Where “Losses loom larger than gains” in our minds (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), suggesting that the psychological pain surrounding a loss is twice as powerful as the happiness that surrounds a gain.

Sunk Cost Fallacy:

Sunk Cost Fallacy is where individuals will continue a behaviour or project to avoid a loss of time, effort, or money they have previously invested or “sunk” into a project and they will keep sinking time, effort, or money into the project to avoid having to cut ties. Research suggests that humans are sensitive to sunk costs after they have decided to pursue a rewar

Dual-System Planner-Doer Model:

The Dual-System Planner-Doer Model is about self-control in decision making and how humans appear to utilise a dual-system for making decisions. This was identified by Thaler as the Planner-Doer Model in 1981 and it was developed upon by Kahneman (& Tversky) as the System-1/System-2 Model in the book “Thinking Fast and Slow” (Kahneman, 2008). The theory explains some people’s ability to invest effort now or to plan/wait for a future benefit. This model further explains the theory of Delayed Gratification.

Delayed Gratification Theory – the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment:

In the 1960’s, Walter Mischel tested 4-year old children’s ability to demonstrate delayed gratification (commonly known as the marshmallow experiment). Following up 10-years later, he found that the ability to demonstrate delayed gratification at this early age was a valid predictor of success in adult life.

Nudge Theory:

Nudge Theory was developed by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in 2008. It suggests that the framing of a choice can significantly change the decision that people make, and so “choice architecture” can help people make “better” choices for themselves (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Nudge theory has now been adopted by several government agencies, including the UK Government’s Behavioural Insights Team. It is hypothesised that nudge theory design can provide the basis for future improvements to increase the number of successful outcomes from this VE programme.

Analysis of Results

Following the juxtaposition of the three groups within the two case study locations (Stage 3 Bereday) in Section 5, a simultaneous comparison is now conducted for the emergence of conclusions and hypotheses in tabular form below (Stage 4 Bereday). This is focused on considering the decision making process for these students looking to make a mid-career change, through the analytical lens of behavioural economics.

The three tables below are constructed with each of the three key questions (outlined Section 5) and are examined separately against each of the relevant behavioural economic theories.

| Behavioural Economic Lens | Why did some people completed the programme and others did not (when technically all of them could have) | Possible Nudges for Further Research |

|---|---|---|

| Prospect Theory (Loss Aversion):- Losses loom larger than equivalent gains in our minds. | Students who completed the programme would have felt “loss” if they hadn’t. Students who did not complete the programme had more inertia to change (or had less self control) than those who completed the programme. They were not driven to complete by a feeling of “loss” and they did not feel there was sufficient “gain” to be realised from completing the programme to reward the effort that was needed to do so. | Promote the idea of loss if students are considering not finishing the programme (e.g. by not completing an end of module assignment) by noting future/lifetime lost earnings from not joining an industry that pays 30% above average for manufacturing jobs. |

| Prospect Theory (Sunk Cost Fallacy):- Research suggests that humans are sensitive to sunk costs after they have made the decision to pursue a “reward” | For students who completed the programme, once they decided to pursue this “reward” they would keep investing time/effort or money until it was realised. The students who did not complete did not feel that they had invested sufficient time/effort or money to trigger their sunk cost fallacy. The students who did not complete either decided that the “reward” they were pursuing was not something they now wanted or their needs had changed. | Trigger feelings of “Sunk Cost” based on the time/effort they have invested to that point, relative to the amount that will be needed to finish the programme (e.g. to complete the final end of module assignment) |

| Duel-System Planner Doer Model:- Ability to invest effort now and plan/wait for a future benefit (Delayed Gratification) | Students who completed the programme displayed an ability for Delayed Gratification (Marshmallow Effect), i.e. they had a more developed Planner/System 2 ability and were prepared to put in the necessary effort to realise the long term reward of a CPD certificate than those who didn’t finish. Those who did not complete the programme are similar to the children who “failed” the marshmallow experiment, i.e. who didn’t have a strong enough ability for Delayed Gratification and instead had a more dominant System 1 approach to human decision making. | This behavioural economics strategy requires further research to be able to find the right “nudge”. An answer may be found in conducting a new experiment similar to Thaler’s experiment on increasing sign-ups and contributions to personal pension plans (Thaler, 2015). |

| Bounded Rationality Theory:- Suggests that humans are satisficers and not optimisers. Humans are bound by 3-things: 1) Amount of Information 2) Cognitive Limitations 3) Amount of Time | Students who didn’t complete (which can be explained by their lack of a feeling of loss or their lack of a System 2 ability) epitomise the underlying way humans make decisions - aiming for a satisfactory outcome, not an optimal one - i.e. it could be due to having stronger satisficer tendencies than optimiser abilities. This means when students had to make a decision about completing the programme - using the 3 things that humans consider when making a decision - completing the programme was not determined to be the most satisfactory outcome, even though in the long term it was the optimal one. | A nudge could be considered to address the “moment before drop out”. Just before dropping out a student will often show signs of “overload”. A proactive nudge by the pastoral support team at that moment could be enough to get the student past the “insurmountable barrier” that is in their mind at that point in time. A model could be based on the Behavioural Insights Team’s study into student dropouts. (Halpern, 2015) |

Table 5. Comparison of why some people finished the courses and others did not, through the analytical lens of Bounded Rationality, Prospect Theory, and Dual-System Planner-Doer Model, with suggested Nudges to increase successful outcomes.

| Behavioural Economic Lens | Why some people got a job and made a mid-career change during/after the programme and others did not (when all of them could have) | Possible Nudges for Further Research |

|---|---|---|

| Prospect Theory (Loss Aversion):- Losses loom larger than equivalent gains in our minds. | Students who got a job and made a mid-career change during/after the programme would have felt “loss” if they hadn’t. The students who did not get a job during/after the programme had more inertia to change (or had less self control) than those who got a job. They were not driven to get a job by a feeling of “loss” and they did not feel there was sufficient “gain” to be realised from getting a job to reward the effort that was needed to do so. Given the large difference between unemployed and employed workers in getting a job, this indicates that being in employment is a big factor in triggering a student’s loss aversion. | Promote feelings of loss if they do not embrace the job hunting process (i.e. making 5 job applications each week), by noting their future/lifetime lost earnings from not joining an industry that pays 30% above average for manufacturing jobs as soon as possible e.g. graphs and tables to reflect delay in getting a new job versus lost lifetime earnings. |

| Prospect Theory (Sunk Cost Fallacy):- Research suggests that humans are sensitive to sunk costs after they have made the decision to pursue a “reward” | Students who got a job and made a mid-career change during/after the programme, once they decided to pursue this goal they would keep investing time/effort or money until it was realised. The students who did not get a job did not feel that they had invested sufficient time/effort or money to trigger their sunk cost fallacy. The students who did not get a job either decided that the “reward” they were pursuing was not something they now wanted or their needs had changed. Given the large difference between unemployed and employed workers in getting a job, this indicates that being in employment is a big factor in triggering a student’s sunk cost fallacy. | Trigger feelings of “Sunk Cost” based on the time/effort they have invested to that point in completing the technical learning on the programme relative to the amount more that will be needed to embrace the job hunting process (i.e. making 5 job applications each week) |

| Duel-System Planner Doer Model:- Ability to invest effort now and plan/wait for a future benefit (Delayed Gratification) | Students who got a job and made a mid-career change displayed an ability for Delayed Gratification (Marshmallow Effect), i.e. they had a more developed Planner/System 2 ability and were prepared to put in the necessary effort to go through the long term process of getting a job than those who didn’t. Those who did not get a job are similar to the children who “failed” the marshmallow experiment, i.e. who didn’t have a strong ability for Delayed Gratification and instead had a more dominant System 1 approach to human decision making. Given the large difference between unemployed and employed workers in getting a job, this indicates that being in employment is a big factor in triggering a student’s System 2 ability. | An answer may be found in conducting a new experiment based around the “Back to Work” scheme nudge, implemented by the Behavioural Insights Team to help increase the number of unemployed workers getting back into employment within 3-months by training/monitoring their System 2 abilities over 2-week job hunting planning cycles - trimmed a million days off unemployment benefits which over a year (Halpern, 2015) |

| Bounded Rationality Theory:- Suggests that humans are satisficers and not optimisers. Humans are bound by 3-things: 1) Amount of Information 2) Cognitive Limitations 3) Amount of Time | Students who did not get a job (which can be explained by not triggering their feeling of loss or their lack of System 2 ability) epitomise the underlying way humans make decisions - where we aim for a satisfactory outcome not an optimal one - i.e. it could be due to having stronger satisficer tendencies than optimiser abilities. This means when these studnts had to make a decision about getting a job and making a mid-career change (using the three things that humans consider when making a decision) getting a job and making a mid-career change was not determined to be the most satisfactory outcome, even though in the long term it was the optimal one. Given the large difference between unemployed and employed workers in getting a job and making a mid-career change, this indicates that being in employment is a big factor in triggering a student satisficer or optimiser abilities. | A nudge could be considered to disrupt the “satisficing” mindset of taking a non-pharmaceutical job just because they were offered it first (or not making a mid-career change at all), e.g. making a career change involves a significant person in the student’s life, and experimenting with getting both of these people (experienced worker and their “partner”) to sign-up to an “optimising” commitment for a period of time. |

Table 6. Comparison of why some people got a job and others did not, through the analytical lens of Bounded Rationality, Prospect Theory, and Dual-System Planner-Doer Model, with suggested Nudges to increase successful outcomes.

| Behavioural Economic Lens | Why are people equally happy with the programme irrespective of whether they have had a “successful outcome” from it or not | Possible Nudges for Further Research |

|---|---|---|

| Prospect Theory (Loss Aversion):- Losses loom larger than equivalent gains in our minds. | The students who had a successful outcome got what they came for, and therefore did not feel “loss”. It is clear as to why this was a positive experience and their happiness was reflected in the survey feedback. Those students who did not feel any loss from not achieving a successful outcome did not have a negative experience, and so were “not unhappy” - not dissimilar to the way children who went home happy after having had only one marshmallow. These students would have done a post-hoc rationalisation and therefore didn’t feel any loss for the marshmallow they never got for the work they never did. This “not unhappy” mindset would have been difficult to distinguish from “being happy” in the survey feedback due to the way in which the questions were framed. | Various Governments have already adopted “nudge” approaches to policy units as they are effective and inexpensive tools that bring about great rewards, e.g. the Behavioural Insights Team UK studies into happiness and well-being measures. (Halpern, 2015) This analysis shows that more students were generally satisfied with the programme, than had a successful outcome from it, i.e. more students who take this mid-career change programme are “happy” and have had a positive experience from it than simply those who had a successful outcome or got a job. These students with an “unsuccessful outcome” still have a positive frame of mind and have ambitions for a better career, have developed an enjoyment for lifelong learning, and have hopes for the future etc, all of which can be. |

| Prospect Theory (Sunk Cost Fallacy):- Research suggests that humans are sensitive to sunk costs after they have made the decision to pursue a “reward” | Students who had a successful outcome got what they came for, once they decided to pursue this mid-career change goal, had a positive experience and their happiness was reflected in the survey feedback. Those students who did not have a successful outcome did not feel that they had invested sufficient time/effort or money to trigger their sunk cost fallacy. So they did not have a negative experience, and so were “not unhappy” - not dissimilar to the way the children who went home happy after having had only one marshmallow. These students would have done a post-hoc rationalisation along the lines of that effort/reward ratio for the first marshmallow had been zero effort and all reward, however to get the second marshmallow required additional effort (above zero) and it would not have justified the reward. This “not unhappy” mindset would have been difficult to distinguish from “being happy” in the survey feedback due to the way in which the questions were framed. | Tapped into going forward by other initiatives. |

| Duel-System Planner Doer Model:- Ability to invest effort now and plan/wait for a future benefit (Delayed Gratification) | Students who had a successful outcome got what they came for and had the necessary Delayed Gratification abilities to get the “second marshmallow” - and it is clear as to why this was a positive experience and their happiness was reflected in the survey feedback. Those who didn’t have a strong ability for Delayed Gratification and instead had a more dominant System 1 approach to human decision making, did not feel any loss and so did not have a negative experience, and were “not unhappy” in a way not dissimilar to the children who went home happy after having had only one marshmallow. This “not unhappy” mindset would have been difficult to distinguish from “being happy” in the survey feedback due to the way in which the questions were framed. |

|

| Bounded Rationality Theory:- Suggests that humans are satisficers and not optimisers. Humans are bound by 3-things: 1) Amount of Information 2) Cognitive Limitations 3) Amount of Time | Students who had a successful outcome got what they came for and made a successful mid-career change had a positive experience - their happiness was reflected in the survey feedback. Those students who did not have a successful outcome still met their satisficer requirements in their decision making process and so did not have a negative experience, and so were “not unhappy” - not dissimilar to the way that children who went home happy after having had only 1 marshmallow, could be deemed to have had stronger satisficer tendencies than optimiser abilities. This “not unhappy” mindset would have been difficult to distinguish from “being happy” in the survey feedback due to the way in which the questions were framed |

Table 7. Comparison of why people were overall satisfied with the programme even if they did not achieve a successful outcome, through the analytical lens of Bounded Rationality, Prospect Theory, and Dual-System Planner-Doer Model, with suggested Nudges to increase successful outcomes.

Discussion

Analysing the Success of the SEC Framework:

The data gathered shows that overall, students are extremely satisfied with both the operational procedures and the content of the VE programme.

Successful outcomes (either completing the VE programme or getting a job) for students are seen to be independent of their years of work experience and previous academic qualifications. This suggests that the online SEC framework is successful in both finding appropriate candidates and comprehensively training them for a career in this high-tech and highly-regulated industry.

When the online Sourcing methodology of the SEC framework is applied to the initial pool of enquiries, it leads to approximately 6% being accepted and enrolled as students. It is suggested that this methodology is creating a normalised pool of candidates who are all a good fit for the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry (and that the industry is a good fit for them).

If this online framework can be successfully applied to this high-tech and highly-regulated industry, it is suggested that it could be applied more widely to identify and train workers for other industries.

Looking to Behavioural Economics to Improve Success:

With successful outcomes independent of the work experience or highest previous academic qualification, 82% of 2017 students and 76% of 2018 students completed the programme and/or got a job. To better understand how to improve on this success, an analytical lens of behavioural economics was applied. Not only do the theories set out possible explanations for unsuccessful outcomes, they provide areas where Governments, policy-makers and other private training providers might look to implement strategies and nudges to increase overall success metrics.

Explaining Overall Satisfaction:

This analysis shows that more students were generally satisfied with the programme, than had a successful outcome from it (i.e. more workers who take this mid-career change programme are “happy” and have had a positive experience from it than simply those who completed the course or got a job).

One hypothesis is that, through the introduction of the career coaching module (the “C” in the SEC framework), participants are gaining confidence in basic job hunting techniques. With this knowledge, they feel confident that they will secure a role, even when they haven’t done so by the time the survey is taken.

This level of confidence in the future and satisfaction in the process means that, even with a current “unsuccessful” outcome, this group remains positive and engaged. These students still have ambition for a better career, hopes for the future, and enjoyment for lifelong learning – all of which can be tapped into going forward with new initiatives. These experienced workers are not shutdown to the lifelong learning process and are open to maintaining their engagement with it.

Further work and follow up is needed to track success metrics over a longer period of time and to identify if there are additional areas of support (or nudges) that could be provided to this group to ensure that their motivation remains consistent throughout their lifelong learning path.

This data might also be useful to help Governments and policy-makers to identify nudges that reframe the benefits of lifelong learning / mid-career change for their citizens and increase the percentage of successful completions (and therefore the pool of resources available) for attracting the next generation of high-paying high-tech industries into areas experiencing a downturn in their traditional or sunset industries.

Conclusion

This paper has presented an online framework for finding appropriate candidates and training them for technician level jobs in a high-tech and highly-regulated industry. Through this study, that framework has been validated and could now be transferred to other industries looking to encourage experienced workers to make a mid-career change, in support of industry expansion.

To better understand and increase the success metrics of this online framework, the field of behavioural economics was examined. Explanations were found for some of the more surprising outcomes of the study, and methods by which future users of this SEC framework might adapt it to improve overall success were proposed.

Governments, policy-makers, and other private training providers can take this versatile online SEC framework and build upon it, tailoring it to their specific needs. Different industry sectors and cultures will likely have to experiment to find those nudges that best move their audience to positive action.

It is proposed that this online SEC framework can be an important step in harnessing the potential of lifelong learning to support sustained and productive industrial growth.

Bibliography

Bereday, George (1964). Comparative methods in education. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York

Cialdini, Robert B (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. HarperCollins Publishers: New York

Cialdini, Robert. (2016). Pre-suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

Cirigliano, Gustavo (1996) ‘Stages of Analysis in Comparative Education’, Comparative Education Review, Chicago, 1996 Volume 10, Part 1.

Collier, Paul. (2018). The Future of Capitalism: Face the New Anxieties. Allen Lane Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

Creaner, Gerard (2015) ‘The Challenge of Delivering CPD Training for the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico within differing policies for a Knowledge Based Economy’ , RWL 9 Conference on Research Work Learning, Singapore, 2015 Volume 1, Part 3, pg 1171 – 1191

De Bruyckere, Pedro & Kirschner, Paul A & Hulshof, Casper D. (2015). Urban Myths About Learning and Education. Elsevier: United Kingdom

Drucker, Peter E (1985). The Effective Executive. HarperCollins Publishers: New York

Dunning, David (2011) ‘The Dunning-Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One’s Own Ignorance’, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, New York, 2011, Volume 44, Chapter 5, pg. 247 – 296

Frank, Robert H (2011). The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition and the Common Good. Princeton University Press: New Jersey

Galbraith, J.K. (1969). The Affluent Society. Second Edition Revised. Hamish Hamilton Ltd.: London

Graeber, David (2019). Bullsh*t Jobs: The Rise of Pointless Work and What We Can Do About It. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

Halpern, David. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How small changes can make a big difference. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

IDA Ireland. (2015). The Pharma Factor. Available: http://www.idaireland.com/newsroom/the-pharma-factor/. Last accessed June 2019.

Jones, P.E (1971). Comparative Education: Purpose and Method. University of Queensland Press: St. Lucia, Queensland

Kahneman, Daniel (2012). Thinking Fast and Slow. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

Keynes, J.M. (1920). The Economic Consequences of Peace. Macmillan and Co. Ltd.: London

Keynes, John Maynard (1921). The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes: VIII Treatise on Probability. Macmillan: United Kingdom

Keynes. J.M. (2017). The General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money. Wordsworth Edition. Wordsworth Editions Ltd: Hertfordshire

Kruger, Justin & Dunning, David (1999) ‘Unskilled and Unaware of it: How Difficulties in Recognising One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self Assessments’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, USA, 1999 Volume 77, No. 6, pg 1121 – 1134

Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Second Edition Enlarged. The University of Chicago Press: London

Lawrence-Wilkes, Linda & Ashmore, Lyn. (2014). The Reflective Practitioner in Professional Education. Palgrave Macmillan: United Kingdom

Meehl, Paul E (Reprint 2018). An Investigation of a General Normality or Control Factor in Personality Testing. FB &c Ltd. : London

Peberdy, Duncan (Edited By). (2014). Creating the Digital Campus: Active Learning Spaces and Technology. DroitwichNet: United Kingdom

Philips, Tom (2018). Humans: A brief history of how we f*ucked it all up. Headline Publishing Group: United Kingdom

Ries, Al & Trout, Jack (1981). Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. Book Press: United States of America

Robson, Colin (2011). Real World Research 3rd Edition. Wiley: United Kingdom

Rooney, Pauline (2005) ‘Researching from the Inside – Does it Compromise Validity’, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2005, Dublin

Russell, Bertrand. (1946). A History of Western Philosophy and its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. George Allen and Unwin Ltd.: London

Samuelson, Paul A. (1980). Economics. Eleventh Edition. McGraw-Hill: United States of America

Simon, Herbert (1945). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organizations. Simon & Schuster: New York

Simon, Herbert (1955) ‘ A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1955, Volume 69, Pg 98-118

Simon, Herbert A. (1996). Models of My Life. Basic Books: United States of America

Singapore Economic Development Board. (2019). Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology. Available: https://www.edb.gov.sg/en/our-industries/pharmaceuticals-and-biotechnology.html Last accessed June 2019.

Singapore Economic Strategies Committee. (2010). High Skilled People. Innovative Economy. Distinctive Global City.

Smith, Adam (1982). The Theory of Moral Sentiments. The Liberty Fund: Indianapolis

Sutherland, Rory (2019). Alchemy: The Surprising Power of Ideas that Don’t Make Sense. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. (2007). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. (2018). Skin in The Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

Thaler, Richard H & Sunstein, Cass R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press: United States of America

Thaler, Richard H. (1992). The Winner’s Curse: Paradoxes and Anomalies of Economic Life. Princeton University Press: New Jersey

Thaler, Richard H. (2015) Misbehaving: The making of Behavioural Economics. W. W. Norton & Company: United States of America

Trott, Dave (2013). Predatory Thinking: A Masterclass in Out-Thinking The Competition. Macmillan: United Kingdom

Trott, Dave (2015). One Plus One Equals Three. Macmillan: United Kingdom

Further Reading

This is one in a series of papers in the area of Lifelong Learning.

You might also be interested in: