Career Change Skills for Experienced Workers

Post COVID-19: Distance Learning to Kick-Start the Economy – Reflections on Career Change Skills for Workers Using the Analytical Lens of Behavioural Science

By Gerard Creaner, Sinead Creaner and Colm Creaner

Publication Date: November 2020

This paper was presented at the 13th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI) 2020

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read):

Abstract

Many Governments are facing the major problem of getting large numbers of people back to work, into different jobs and careers over the next 6-12 months during 2020-21, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The standard reskilling programmes with in-classroom, in-person delivery and assessment methods cannot be simply transposed into an online environment with little modification, as this approach does not always work.

Likewise technical training alone for these experienced workers is not enough. Many of them are in their thirties and forties and have had this career change imposed upon them by these extraordinary circumstances and the economic decisions that were taken by Governments to control it. These experienced workers are unprepared for how to go about finding a new job and building a new career in a new industry at this stage of their working lives.

This paper examines the experiences of a private training provider in implementing an online career coaching programme in addition to a technical one, for experienced workers looking to make a transition into a new industry. Not surprisingly, the addition of career change skills to new technical ones enhanced the direct benefits of securing a new job more quickly for these workers. However when given the option of completing both the technical module and the career coaching module, 80% of experienced workers choose to do only the technical module.

Given the benefits of adding the career coaching, it was decided to make it mandatory for everyone to complete it, however the question remained as to why did these otherwise capable experienced workers not want to do it.

Post completion surveys of these workers found that the career coaching programme also has the indirect benefit of increasing their confidence in the future, even if they didn’t secure a job from the reskilling initiative, which in turn made them more open to engaging with future Government initiatives in this area. This indirect benefit is of great value to Governments who will be making significant investments in reskilling initiatives, as this will ensure that every reskilling programme with combined technical and career coaching elements will have broader benefits to more workers than simply rolling out a technical one.

The combination of direct and indirect benefits from making the career coaching programme mandatory led to the key research question, “Why the mandatory inclusion of this career coaching skills module (which the experienced workers would not have chosen to do by themselves) increased their confidence in the future, and their attitudes to lifelong learning?”.

When looking to answer this key research question, the analytical lens and theoretical framework of Behavioural Science was applied, in particular Bounded Rationality and Dual-System Planner-Doer Models. These suggest some explanations for the behaviour of these experienced workers and the positive outcomes from having completed a career coaching module that they did not want to do in the first place.

The key outcome from this research will have great benefits for Governments in kick-starting their economies, identifying best practices for incorporating online career change skills programmes alongside technical training ones. These can be implemented in major training investments by Governments through education providers, so as to get more effective outcomes when engaging with retrenched workers through back-to-work initiatives.

Keywords: Online Learning, Behavioural Science, Adult Learners, Career Coaching, Experienced Workers, Reskilling

Introduction

Career change has been imposed on many experienced workers all around the world as a result of the economic fallout following the Government decisions that were made to control the COVID pandemic. In a world where increasingly there are no longer “jobs for life”, experienced workers need to have the ability to upskill themselves so as to be able to make multiple job changes over their working lives.

Following the COVID pandemic and the subsequent social distancing measures implemented by Governments, research into online learning has never been more relevant, with the upcoming back-to-work programmes Governments will be implementing to kick start the economy.

This paper takes the experiences of a private training provider in reskilling experienced workers for new jobs in new industries. It uses the data and insights generated to provide a unique perspective on the key elements of a reskilling framework, combining online career change skills with relevant technical programmes to transition experienced workers into new jobs and careers.

The data set has been gathered over a three-year period (2017/18/19) from over 500 adult learners, coming from a variety of educational and employment backgrounds, with 5 to 25 years of work experience. All were exposed to the same technical and career coaching programme.

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

Conceptual Framework

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

In Bereday’s model, ‘everyday’ comparability is distinguished from socially-scientific or laboratory methods. The everyday comparability approach fits with individualistic practitioner research in that it favours establishing relations between observable facts, noting similarities and graded differences, drawing out universal observations and criteria, and ranking them in terms of similarities and differences.

In everyday comparability, the view is subjectively from within and deliberately without perspectives detachment. It focuses on group interests, social tensions, impact factors and collective beliefs, patterns, and behaviours as experienced by the authors.

In terms of analytical steps, this paper uses Bereday’s four stages as illustrated by Jones (Jones, 1971), as follows:

- Stage 1: Description of each case using a common approach to present fact

- Stage 2: Interpretation of the facts in each case using knowledge other than the authors

- Stage 3: Juxtaposition for preliminary comparison using a set of relevant criteria

- Stage 4: Simultaneous comparison, emergence of conclusions and hypotheses

The perspective in this paper is the authors’ own as the private training provider of vocational education programmes, mindful of the particular risks of insider research (Rooney, 2005).

Current Practice

Over the last 3-years, over 500 experienced workers have taken this career change skills programme, and with each group, there has been a refinement of how the career change programme has been implemented, based on the feedback that has been received in the annual post-programme survey.

The career coaching programme covers the basics of how to find a new job, in a new industry including where to look, how to write a CV, interview skills, and the key transferable skills than an experienced worker is bringing to the new industry.

Most importantly, as these experienced workers are going through a career change, some are overconfident about their job hunting capabilities, and others are unduly worried. At the start of the programme, the experienced worker’s job huntings capabilities are measured using a short 10-question survey (called the Job Hunting Baseline quiz). This questionnaire is used to normalise both groups. After the completion of the 5-week module, the same quiz is retaken, to demonstrate to the learner how far they have come in only a month. The results of these short quizzes will be discussed in the next section.

The key changes made to the career coaching programme across the group of 500 experienced workers is as follows:

- 2017 – the career coaching programme was offered to everyone. However, only 19% of students availed of this option. In the post-programme survey however, there was very positive feedback from them about the programme.

- 2018 – the career coaching programme was offered to 50%, and was mandatory to complete for the other 50%. There was a subsequent rise in the percentage of experienced workers who secured employment – and there was a significant increase in the student’s positive outlooks on lifelong learning and job security.

- 2019 – the career coaching programme was made mandatory for everyone. There was another rise in the percentage of experienced workers who found a job, as well as another increase in the positive outlooks on job security and lifelong learning.

The data for each of the years will be discussed in more detail in the next section – Research Findings.

Research Findings

The data gathered for this paper is quantitative. The limitations of quantitative studies – as potentially statistically relevant due to large data sets while being humanly irrelevant, missing the contextual details surrounding the results – are acknowledged. However, in this case, in the straddling between insider-actor mode and outsider-observer mode (Robson, 2011), and due to the research question in hand, the research generated provides a large enough basis on which to build observations.

For the purposes of this paper, a demonstration of the movement of grade distribution on the job hunting baseline quiz from before they started the course to after they finished it. The same quiz was given in both circumstances to demonstrate a difference in grade before and after the course of study. This data representation is the clearest way of demonstrating the effectiveness of the career coaching programme on these experienced workers, as visually this difference is very apparant, moving from low-to-medium grades for all the workers at the start to medium-to-high grades at the end.

The data for this paper was gathered directly by the training provider using tools including online quizzes through the Moodle platform. The data has been processed for ease of reading using Moodle’s graphing tool as this was the purest way to graphically represent the data without excluding any outliers. There is a change between the number of students on the course at the beginning and at the end, this is due to the student drop off rate on the course as other factors prevented them from studying and completing the course.

2017 started documenting data on the students who completed the course, specifically about how many of the workers who actually took the course recognised the help that it gave and whether this was demonstrable. Based on this data, it was possible to gain a preliminary idea of how the students saw our course and the benefits that it provided to them in their life.

Then in 2019, it was decided to revamp this method of surveying the students by expanding the areas investigated. This has resulted in a much more in detail understanding of specifically how and where the career coaching helps the experienced workers taking these programmes. This has also allowed the provider to edit the course further, putting more emphasis on the areas that were marked as more relevant to the students career.

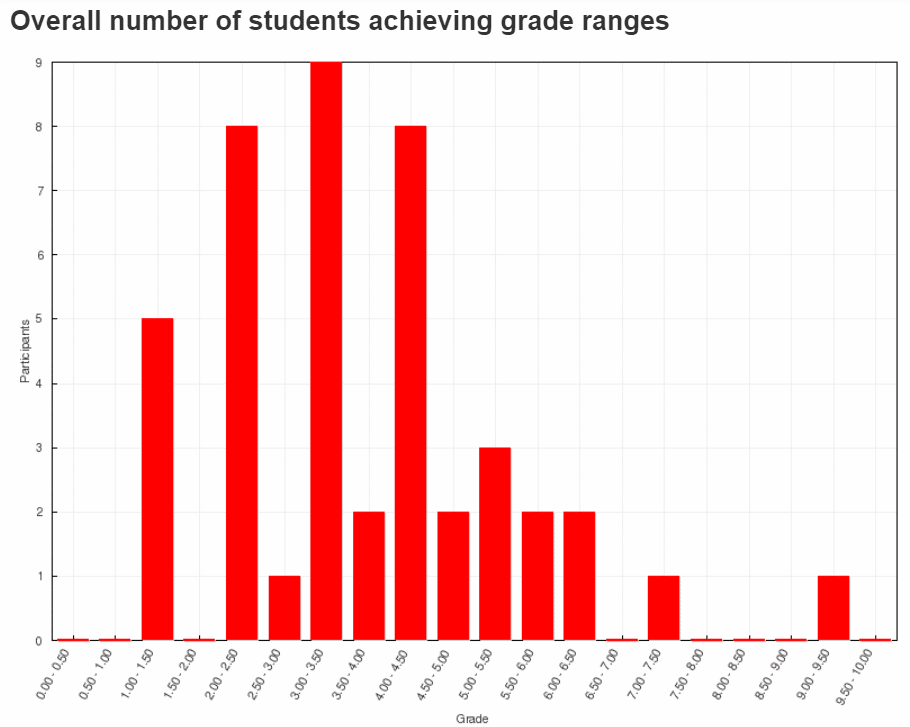

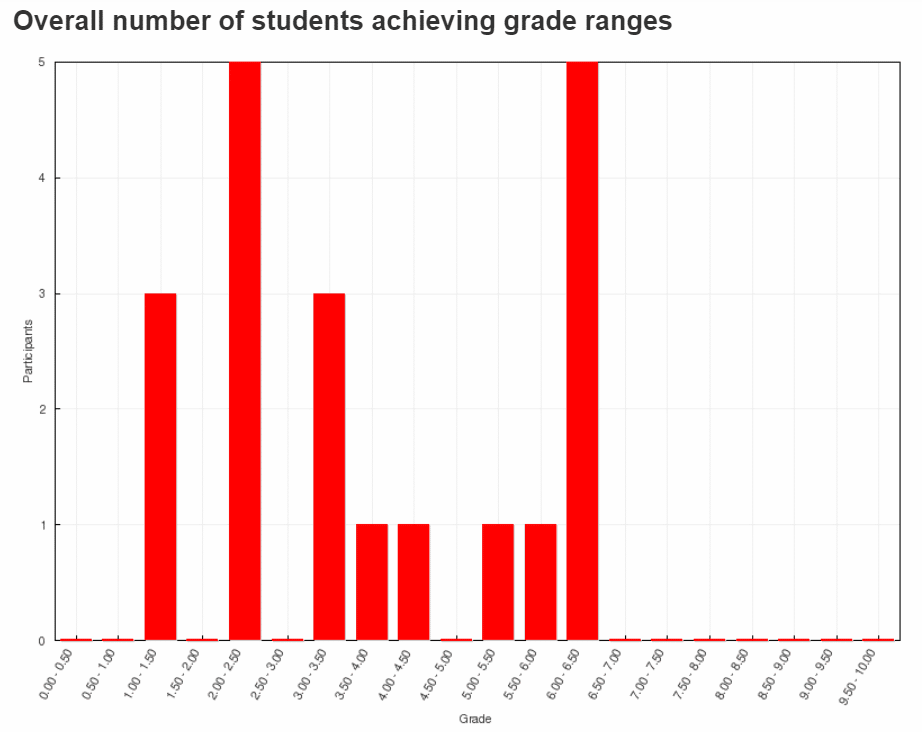

(Class 1 Before Taking Course – 44 Students)

(Figure 1)

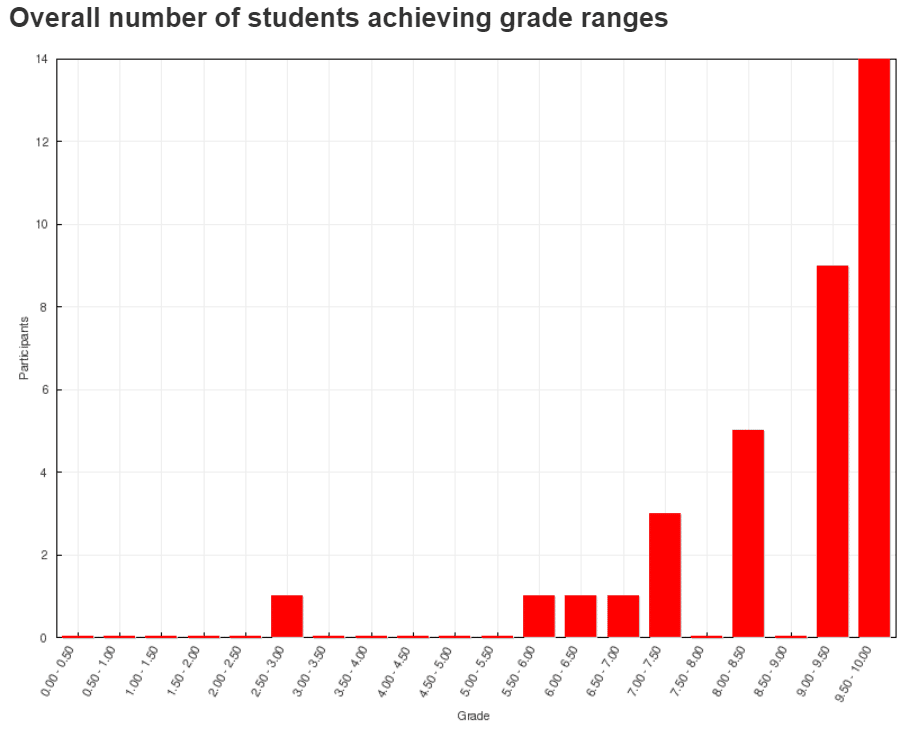

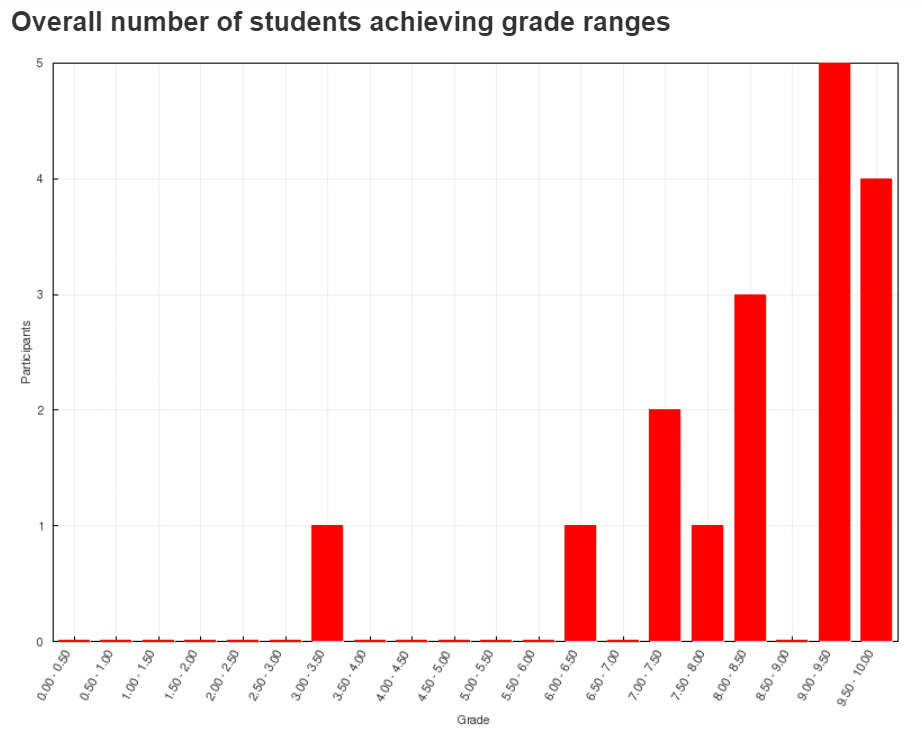

(Class 1 After Taking Course – 35 Students)

(Figure 2)

Figures 1&2: Bar charts of number of people and their associated grade achieved in the same Job Hunting Quiz before and after taking the course.

The 2 key points to be considered from this are:

- As can be seen from the graphs there is a significant shift to the Right across all the grades (i.e. higher grades) between start and finish of the career coaching course.

- In the post-module survey, 22 of the initial 35 students found a job using the methods that they learned from the course (63% out of all students that finished the course).

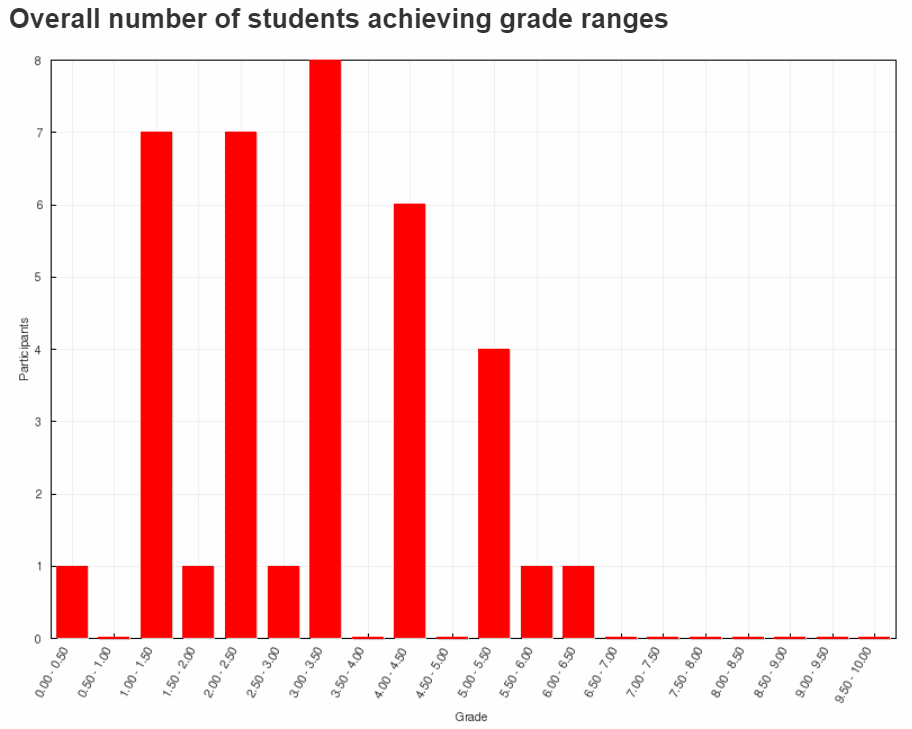

(Class 2 Before Taking Course – 20 Students)

(Figure 3)

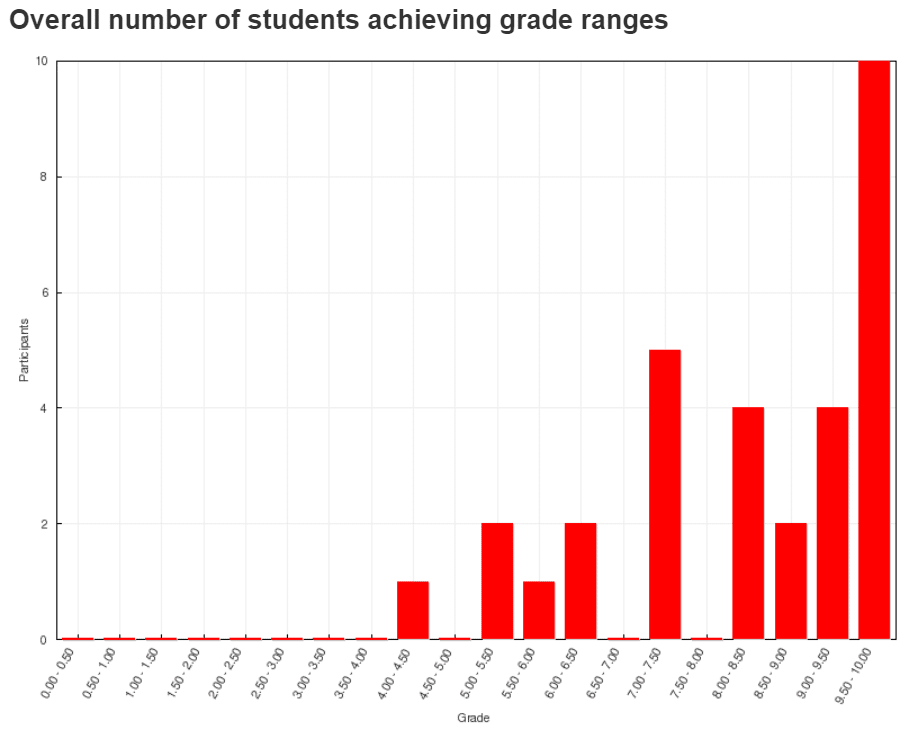

(Class 2 After Taking Course – 31 Students)

(Figure 4)

Figures 3&4: Bar charts of number of people and their associated grade achieved in the same Job Hunting Quiz before and after taking the course in Class 2 for comparison of the performance of other classes.

The key point to be considered from this is:

- Once again the graphs show a significant shift to the Right across all the grades (i.e. higher grades) between start and finish of the career coaching course.

(Class 3 Before Taking Course – 20 Students)

(Figure 5)

(Class 3 After Taking Course – 17 Students)

(Figure 6)

Figures 5&6: Bar charts of number of people and their associated grade achieved in the same Job Hunting Quiz before and after taking the course in Class 3.

These graphs were put in for more points of comparison between the classes as the wider data set the better we are able to see trends

The key point to be considered from this is:

- The distribution of students once again shifts to the Right (i.e. higher grades) after the end of the course, to reflect the knowledge that they gained through the course.

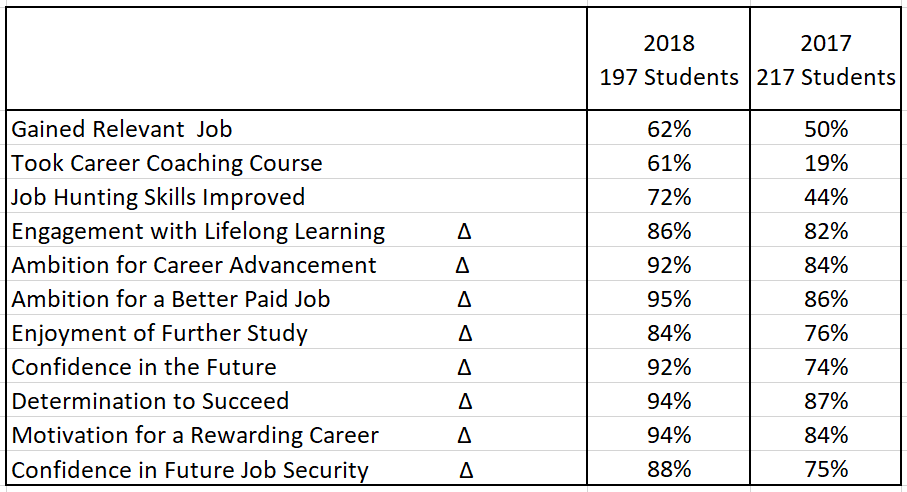

The original post-programme survey (2017 and 2018 students) looked to measure the percentage who gained employment, the percentage who took the course, and the student’s overall outlook on lifelong learning, job security and confidence in the future. Table 1 below details these results: (Please note that Δ means “increased”)

(Data Gathered in 2017 & 2018)

(Table 1)

The key points of this table are:

- The proportional increase in the percentage of people who gained a relevant job after taking the career coaching course.

- In addition to this the addition of this course contributed to the mental wellbeing of our students as their confidence in the future increased

- Due to the increased number of people who have gained employment due to this course, there has been a correlated increase in their confidence in their future job security, further demonstrating that this course is both beneficial for the workers as it aids to their gaining of employment.

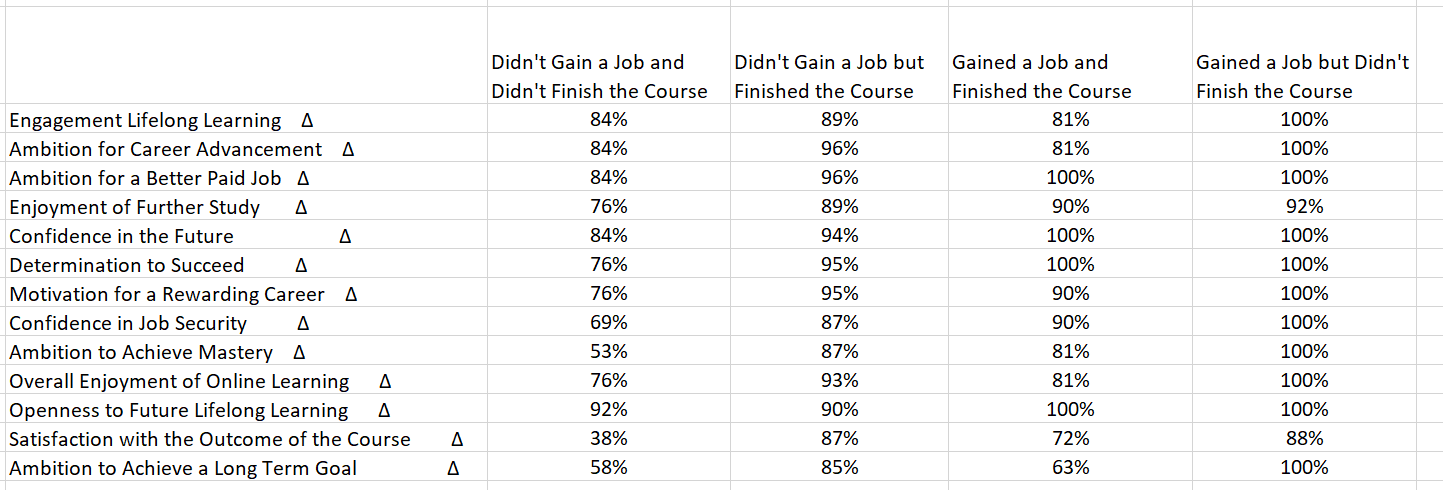

Table 2 below, details in much more depth the post-programme 2019 survey, where the response the students gave on each of the questions regarding their outlook on life, was categorised with respect to Job Success and Course Completion.

(Data Gathered in 2019)

(Table 2)

The key points of this table are:

- The further breakdown of the courses results has allowed us to see that the student’s engagement with lifelong learning irrespective of gaining employment or even finishing the course is high, meaning that these students are likely to either take another course or suggest that others take a course.

- In addition to this, courses like this improve the confidence and motivation of the student irregardless of the outcome as they feel as if they as a person have progressed and gained skills that make them more employable, in turn making them more likely to take one of these courses again and engage with Government back-to-work programmes.

All of these points together led to the key research question of this paper:

“Why the mandatory inclusion of this career coaching skills module (which the experienced workers would not have chosen to do by themselves) increased their confidence in the future, and their attitudes to lifelong learning?

Theoretical Framework for Analysis

Previous research from this private training provider was reported at the Research Work Learning Conference 2015 in Singapore, the ICDE World Conference on Online Learning 2019 and the IMSCI Conference 2020. This work found the lens of Behavioural Science to be particularly useful to interpret the decisions of learners in an online environment. This current analysis further builds on those ideas.

Behavioural Science is the study of human motivation, decision making, and actions. It tries to understand how people interpret information; why they make the decisions they do when faced with multiple options; and, ultimately, why people behave the way they do.

The analytical lens of behavioural science suggests some explanations in answer to the key research question.

Overview of the field of Behavioural Science:

As a species, humans have evolved a strategy of decision making that uses mental shortcuts – or heuristics – to allow subconscious decision making.

Colloquially – these heuristics are called “rules of thumb”. Daniel Kahneman describes this process as basically trading a difficult question, for an easier one within our brains. While there is an evolutionary advantage for using these rules of thumb in the increasingly complex world in which we live, they can lead to cognitive biases.

A cognitive bias is a systematic error in thinking. In other words, the decision that arose was due to an error in how information was processed due to an inherent reliance on our innate heuristic.

Herbert A. Simon is seen as the founder of modern behavioral science, after winning the Noble Prize for Economics in 1978 for his theory of Bounded Rationality. He demonstrated that humans make decisions to achieve a satisfactory outcome, rather than an optimal one because our decisions are made on the knowledge we have, our ability to process this knowledge, and the amount of time we have to make the decision (Simon, 1955). This suggests that learner’s abilities to implement the knowledge they receive on career coaching is dependent on these three factors.

Key Behavioural Science Concepts for this Paper:

There are 12 key behavioural science concepts when examining this research question:

- Ambiguity (uncertainty) aversion – this is the tendency to favour the unknown over the known due to an innate fear of unknown risks. (Ellsberg, 1961)

- Availability Bias – this is when judgements are made about the likelihood of an event based on how easy it is to recall a case that comes to mind. (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974)

- Choice Architecture – is when changing how a choice is laid out, changes the context in which a person makes a decision (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

- Confirmation Bias – is the tendency to use hindsight to confirm that our choices are the right one’s (even if this wasn’t the case) (Wason, 1960)

- Default (option) – are the set courses of action that will happen, and this can work as a very effective nudge when looking to change the decision of a group of people (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008)

- Delusion of competence (Dunning – Kruger Effect) – this is when a person lacks the ability to properly reflect on their own abilities/knowledge. (Kruger and Dunning, 1999)

- Hindsight bias – this is what happens when new information changes how we recall our previous actions/thoughts on a situation (Mazzoni & Vannucci, 2007)

- Inertia – is when things stay the same due to a person’s inaction (Madrian & Shea 2001). Nudges can work with people’s innate inertia or against it (Jung, 2019).

- Information Avoidance – is also known as the Ostrich Effect, and it is where people choose not to obtain knowledge that is freely available because they expect a negative outcome from receiving it.(Sullivan et al., 2004).

- Myopic Procrastination – this is the tendency to avoid decisions due to the complexity of decision-making (BE Guide, 2020).

- Overconfidence Effect – this is the tendency to overestimate our own abilities in relation to our actual capabilities. (BE Guide, 2020)

- Social norms – this is the tendency to follow what is perceived as the appropriate behaviour based on the rules within a group of people (Dolan et al., 2010).

Analysis & Discussion

Based on the research findings and the theoretical framework, the overarching research question of “Why the mandatory inclusion of this career coaching skills module (which the experienced workers would not have chosen to do by themselves) increased their confidence in the future, and their attitudes to lifelong learning?”,

This question can be broken into three parts:

- Why did 80% refuse the Career Coaching Course when it was an option?

- Why were people happy to do Career Coaching when the option of not doing it was taken away, i.e. it was made mandatory?

- Why did the mandatory implementation of a career coaching course have a positive impact on the experienced workers outlook on job security and lifelong learning, when they didn’t want to do it in the first place?

A simultaneous comparison is now conducted for the emergence of conclusions and hypotheses in tabular form below (Stage 4 Bereday). Table 3 (below) shows the analytical lens of behavioural science, laid over the question.

| Why did 80% refuse the Career Coaching Course when it was an option? | |

|---|---|

| Availability Bias | The experienced worker made a judgement on their need for career coaching help in reference to their memory of how easily they found a job last time, and any feedback they had received from recent unsuccessful job interviews, (e.g. we need someone with more technical skills for the role,) as feedback about poor job hunting skills is rarely given as it is very personal and open to misinterpretation. |

| Confirmation Bias | The experienced worker, as an experienced worker, has already conducted at least one successful job hunt (to secure their last position). Based on this information, confirmation bias kicks in to tell themselves that they have the adequate skills to find a job already. |

| Delusion of competence | Many experienced workers suffer from the delusion of competence when considering job hunting skills or career coaching – even though the case study shows that in most cases, they do not have the skills to meet the demands of the situation. This led to 80% refusing the career coaching module when it became available – as when coupled with hindsight bias, confirmation bias and availability bias, the experienced worker felt they did not need a skills improvement in this area. |

| Information Avoidance | Experienced workers who have not had to job hunt in a number of years, often experience the ostrich effect when it comes it job hunting, as while on an instinctual level they may feel they need job hunting (as proven with the results from the initial baseline job hunting quiz), they are not eager to seek out the information as they fear it will be negative. |

| Overconfidence Effect | Experienced workers suffer from overconfidence when considering job hunting and career coaching. They feel as they have already successfully conducted one job hunt themselves without any additional help, and so they will be able to repeat this process without assistance this time. The job hunting baseline quiz, is used to normalise and mitigate this heuristic. |

| Why were people happy to do Career Coaching when the option of not doing it was taken away, i.e. it was made mandatory? | |

| Choice Architecture | By removing the decision regarding whether to take combined career coaching and technical programme or to take just the technical course by itself, there was a choice to be made about which course format to take. The choice architecture was then changed to a much simpler context of “will I take the combined course or not do any course”. The choice architecture changes from two choices to effectively no choice i.e. do it as it is or don’t do it at all. |

| Default (option) | By making the career coaching course mandatory, the default option was set, removing any uncertainty from the thinking processes of the experienced workers. |

| Inertia | The removal of a choice from the choice architecture regarding whether or not to take the career coaching course, worked with people’s desire for inertia, rather than against it, and hence why experienced workers, accepted having to complete a career coaching module when it became mandatory. |

| Social Norms | Currently, job hunting and career coaching is seen as something people should already know how to do. Social norm dictated then, when it was a choice, not to take the career coaching module. However, when it became mandatory, the social norm changed, and instead it dictated that the experienced worker should complete the module. |

| Why did the mandatory implementation of a career coaching course have a positive impact on the experienced workers outlook on job security and lifelong learning, when they didn’t want to do it in the first place? |

|

| Ambiguity (uncertainty) aversion | By removing the uncertainty around job hunting, through the teaching of a process of how to find a job (i.e. give a man a fish), there was a removal of future unknown “risks” surrounding their job – as they now know how to find a job, even if they lose their current job. This has had an overall positive impact on their outlook regarding their future and the usefulness of lifelong learning – as there is less fear of a change in the status quo, and lifelong learning has a big impact in the reduction of this fear of uncertainty. |

| Hindsight bias | While the experienced workers may have felt they did not need the career coaching module at the outset, when the job hunting process was taught and absorbed, hindsight bias took effect and changed their original feelings on its relevance and importance, especially when it helped reduce their feelings of uncertainty about the future. Overall, this led to positive recollection of the course, and this was measured in the post course completion survey. |

| Myopic Procrastination | The career coaching course worked with the experienced workers innate heuristic of myopic procrastination to overcome it. By simplifying the job hunting process into very distinct and actionable steps, there was no need to put off the decisions and actions that needed to be made regarding hunting for a new job, leading to overall greater feelings of satisfaction and direction post the course. |

Conclusion

This paper examines the direct and indirect benefits from making the online career coaching programme mandatory for experienced workers, as compared to only requiring them to complete the technical elements of a reskilling programme.

The case study found that 75% of the trainees achieved either one or both of what would be normally deemed as the only positive outcomes from such a training initiative, i.e. successfully completed the programme and/or got a job. So 25% of the trainees did not achieve either one of these successful outcomes, and would be expected to have a neutral view of the programme (and their future prospects as a result of it) at best. However 94% of trainees reported an increase in confidence in the future, their happiness with the course, a willingness to do another programme etc. So 20% more trainees had a positive outcome than those who had what would be normally deemed a positive outcome from a reskilling programme, as a result of the mandatory inclusion of a career coaching programme along with the technical modules.

Since there was extensive screening prior to offering places on the programme, it is reasonable to assume that all the experienced workers accepted onto this online programme were capable of completing it and subsequently getting a job offer. Yet those who didn’t complete the programme or find a job did not have negative feelings about the reskilling programme or engaging with other future lifelong learning programmes.

This outcome has great benefits for Governments in kick-starting their economies, as expenditure will significantly outweigh taxation income in order to restart the economy and get people back to work. Best practice for incorporating career change skills programmes alongside technical training ones is key to reskilling workers, and will significantly increase their return on investment of taxpayers monies on these initiatives. As well this, Governments will realise additional benefits in creating a workforce that is more disposed to engaging with future back-to-work initiatives when the need arises.

In conclusion, this paper is of particular relevance at the current time as the world enters the last quarter of 2020 and looks onto 2021. A post-COVID world will require more reskilling initiatives to be completed within an online environment and adding a career coaching element to the current reskilling frameworks has never been more necessary.

Conference Presentation

These findings have been presented at the ICERI 2020 conference in Spain.

References

[1] Creaner, Gerard (2015) ‘The Challenge of Delivering CPD Training for the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico within differing policies for a Knowledge Based Economy’ , RWL 9 Conference on Research Work Learning, Singapore, 2015 Volume 1, Part 3, pg 1171 – 1191

[2] Creaner, Gerard (2019) ‘Harnessing the Potential of Online Learning to Build Effective & Sustainable Lifelong Learning Frameworks: Case Studies from Ireland and Singapore’, ICDE World Conference on Online Learning, Ireland, 2019, Volume 1, Part 1, pg 128-145

[3] Halpern, David. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How small changes can make a big difference. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

[4] Jones, P.E (1971). Comparative Education: Purpose and Method. University of Queensland Press: St. Lucia, Queensland

[5] Robson, Colin (2011). Real World Research 3rd Edition. Wiley: United Kingdom

[6] Rooney, Pauline (2005) ‘Researching from the Inside – Does it Compromise Validity’, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2005, Dublin

[7] Shields, Patricia; Rangarajan, Nanhini (2013). A Playbook for Research Methods: Integrating Conceptual Frameworks and Project Management. New Forums Press: United States of America

[8] Simon, Herbert (1955) ‘ A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1955, Volume 69, Pg 98-118

[9] Thaler, Richard H & Sunstein, Cass R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press: United States of America

[10] Thaler, Richard H. (2015) Misbehaving: The making of Behavioural Economics. W. W. Norton & Company: United States of America

Further Reading

This is part of a series of papers in the area of Career Coaching.

You might also be interested in: