New Approach to Academic Writing

Reflections on implementing a Behavioural Science based approach versus current best practice, for explaining referencing and plagiarism to adult learners, in an online learning environment.

By: Gerard Creaner, Sinead Creaner and Colm Creaner

Publication Date: June 2021

This paper was present at the 13th Annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (EDULearn) 2021

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read):

Abstract

This paper examines one private training provider’s reflections on implementing a new Behavioural Science based approach versus current best practice, for explaining referencing and plagiarism to adult learners, who were studying in an online learning environment.

This paper builds upon previously presented research by the authors. It was proposed that using Behavioural Science theories and positive messaging to explain referencing and the responsibilities of academic writing to adult learners returning to education, could reduce plagiarism scores, and increase the quality of assignments. In addition, these adult learners would experience increased confidence in their own opinions as they related to subject matter experts in the field, while also reducing the workload of the lecturers in the reporting requirements for documenting plagiarism in the university quality systems.

For this paper, a pilot group of 21 adult learners were given a writing skills course, developed using behavioural science theories and positive messaging, to run concurrently with the time allocated for an end of module assignment on a course module. Their plagiarism scores and assignment grades were then compared to a written assignment from an earlier course module they had completed, where they had been given standard negative messaging regarding plagiarism and referencing, and the penalties associated with not adhering to them.

The results of the two assignments were compared, to draw any conclusions between the effectiveness of the different systems with respect to the grades achieved on the assignments and the associated plagiarism scores.

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

The percentage of online learning relative to classroom based teaching is likely to increase across many courses in a post-COVID world. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of plagiarism in an online environment and the strategies for mitigating it, will become a central element of many universities’ quality standards. In addition, this research could give insights to Government policy-makers and universities looking to implement strategies to improve the learning experience for students studying in an online environment.

Keywords: Online Learning, Referencing, Behavioral Science, Online Assessment, Plagiarism, Adult Learners, Best Practice

Introduction

This research project has been developed to test some insights from the recommendations of a previous paper by the same authors. The findings of that research were presented at the International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics 2020 (IMSCI) and published in the Journal on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (JSCI).

That research project looked at the experience and effectiveness of implementing a standard plagiarism awareness campaign in an online learning environment, and it used the analytical lens of behavioural science to examine the results (where plagiarism scores were High for almost 20% of adult learners due to their poor referencing abilities).

Two key takeaways from that Research Project were:

- Current best practice campaigns for plagiarism do work, but they still result in high plagiarism scores due to poor referencing capabilities of up to 20% of the students.

- The possibility of a new approach using Behavioral Science theories could do more than just catch plagiarism, it could also improve the quality of assignments, the confidence of the students, and reduce the workload of the lecturers associated with the reporting requirements for documenting plagiarism in the university quality systems.

To test these hypotheses, the researchers developed an online writing skills course underpinned by behavioural science theories, and delivered it a small pilot group of experienced workers who had previously submitted assignments where they had been given standard negative messaging regarding plagiarism and referencing, and the penalties associated with not adhering to them.

This paper will discuss:

- the demographics of the pilot group

- the relative engagement of different students with the Writing Skills course

- a comparison of the grades and plagiarism scores for the two assignments (before and after the Writing Skills course)

The conclusion will document what can be inferred from the introduction of the online Writing Skills course to this pilot group of experienced workers as it relates to increased grades and reduced plagiarism scores, and the potential relevance of these findings for larger groups of students.

Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Framework

Bereday’s Model for Comparison:

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

In Bereday’s model, ‘everyday’ comparability is distinguished from socially-scientific or laboratory methods. The everyday comparability approach fits with individualistic practitioner research in that it favours establishing relations between observable facts, noting similarities and graded differences, drawing out universal observations and criteria, and ranking them in terms of similarities and differences.

In everyday comparability, the view is subjectively from within and deliberately without perspectives’ detachment. It focuses on group interests, social tensions, impact factors and collective beliefs, patterns, and behaviours as experienced by the authors.

The perspective in this paper is the authors’ own as the private training provider of vocational education programmes, mindful of the particular risks of insider research (Rooney, 2005).

Action Research:

This paper is part of a broader set of work utilising an action research approach, where the authors’ work through the 7-step process in a continuous cycle as per Ernest Stringer’s Action Research Interacting Spiral (Stringer, 1996).

Behavioural Science:

The theoretical framework in which this paper is based, is the field of Behavioural Science.

Behavioural Science is the study of human motivation, decision making, and actions. It tries to understand how people interpret information; why they make the decisions they do when faced with multiple options; and, ultimately, why people behave the way they do.

The aim of the field of behavioural science is to understand and apply the “human factor” to the decision-making process, rather than building theories on people making simple rational/logical decisions and choices, i.e. the theoretical concept of the logical/rational “Economic Man”.

Herbert Simon is seen as the founder of modern behavioral science, after winning the Noble Prize for Economics in 1978 for his theory of Bounded Rationality. (Simon, 1955).

The 4 key behavioural science concepts covered in this paper are:

- Bounded Rationality (Simon, 1955) – Humans make decisions to achieve a satisfactory outcome, rather than an optimal one. People do not “perfect” decisions because decisions are made based on the knowledge an individual has, their ability to process that knowledge, and the amount of time available to make the decision.

- Framing Effect (Tversky & Kahneman, 1978)- Explains that the way information is presented to an individual changes how it is interpreted. In other words, if the same information is presented in a positive manner or a negative manner, a person’s interpretation of the information and the decisions they make about it, will change.

- Simplification Theory (BIT, 2016) – Suggests that an individual is more likely to act on a message if it is easy to understand.

- The Messenger Effect (BIT, 2016) – Suggests that people give different weight to arguments, depending on who presents them and an individual is more likely to act on information received from an expert or from someone respected.

Previous Research

Previous research from these authors reflected on the effect of implementing best practice for referencing and plagiarism amongst adult learners who were studying in an online environment.

The general consensus on plagiarism, from the perspective of academic writing, is that:

- Despite a conceptual awareness of the topic of plagiarism, students lack the understanding to take this knowledge and implement it.

- Most common forms of plagiarism were a lack of proper acknowledgment when paraphrasing and summarizing.

- Implementing a standard awareness campaign covering the basics of referencing and the negative consequences of breaking these rules, will resolve the issue with the majority of culprits. (Selemani et al, 2018) – and this is considered “best practice”.

However, the research presented at the IMSCI 2020, also looked for potential areas of improvement in light of the suggestion from Dr. Zeljana Bašić (Bašić, 2019) that significant changes need to be implemented within academic environments to foster a positive climate within which learners can understand their responsibilities when writing.

The research was based around the assignment grades and associated plagiarism scores of 275 adult learners measured over a two-year period (2017-2019). Half of these adult learners studied a non-academically accredited module and the other half completed an academically accredited module at an undergraduate level. All participants were looking to make a mid-career change into the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device manufacturing industry. Both groups received the same standard awareness campaign on plagiarism that was routed in “best practice”, which included:

- A two-page guide covering what plagiarism is, how to avoid it, and why it is serious. This was shown at the top of each course page for the entire duration of the students studies and was reissued with each assignment.

- Advice to contact a member of staff with questions or queries on plagiarism and how to avoid it.

- Learners were also reminded that as they were entering a life-critical industry where the safety of patients relies on their honesty and adherence to strict protocols, plagiarism (unintentional or not) raised a significant red flag on their suitability to work in such an industry.

All the assignments were then processed through the same standard plagiarism software (Grammarly), to establish a plagiarism score. The lecturer then determined whether the issue was due to malicious plagiarism or poor referencing. If the assignment conclusions were deemed to be the learner’s own, the assignment could pass, despite poor referencing.

The findings showed that almost 20% of adult learners had a High plagiarism score and as those demonstrating malicious plagiarism had been excluded from the study, it was concluded that these figures were a result of poor referencing skills. This resulted in learners with poorly supported arguments, and likely sub-optimal grades, as well as lecturers dealing with an avoidable workload of investigation and documentation of these plagiarism scores.

This presented the key question: How can the poor referencing abilities of otherwise capable learners be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring?

Using the analytical lens of behavioural science (in particular the theories of Bounded Rationality, the Framing Effect, the Messenger Effect and Simplification Theory), an area for further study was established, centering around the idea of creating a positive environment for learners to explore referencing and building more credible arguments through the proper use of SME opinions that support their own, rather than the current situation where referencing is seen as a box-ticking exercise that results in punishment if not done correctly.

This led to the development of a Writing Skills module which was issued to a Pilot group of 21 students.

Writing Skills Module

The Writing Skills module was designed to improve the students’ written communication skills and understanding of their responsibilities in academic writing.

The module covered how to plan an essay; how to organise ideas; how to draft and edit the piece of writing; how to build credibility in written communication through the use of behavioural science; how to gather information; and how to identify and judge a source’s credibility.

The online module (approximately 50 hours of study) was designed to be completed in conjunction with a technical module’s existing end-of-module assignment. In the case of the pilot group, this took the form of a 3,000-word technical essay.

This allowed the students to apply the learnings immediately, where a direct benefit could be seen, and differs from the standard approach to teaching academic writing as stand alone. The theory for this decision was based in the findings of Dirksen, Colvin Clark, Stolovitch, and Keeps as:

- Procedural memory needs practice (Dirksen, 2016)

- When learning something new, new connections are formed in the students brain, and each time that new piece of information or skill is used, the connection is strengthened (Dirksen, 2016)

- The biggest improvement in a skill comes from the first few practices (Dirksen, 2016)

- Embedded retrieval hooks at the time of learning – opportunities that give the students real-life practise of using the information – make practising and using this skill easier (Colvin Clark, 2010)

- Therefore assessments that ask students to implement the information, have the greatest impact in the long term (Stolovitch & Keeps, 2011)

The module is based on the insights from the author’s previous research in this area, utilising tools from Behavioural Science to foster a positive environment for learners to explore referencing and building more credible arguments through the proper use of Subject Matter Experts (SME) opinions that support their own. The underlying layout of the module addressed the 4 key behavioural science traits surfaced in previous research as per Table 1.

| Behavioural Science Theory | Finding from Previous Research | How does the Writing Skills module address this? |

|---|---|---|

| Bounded Rationality Suggest that humans are satisficers, not optimisers | Learners are impacted by the amount of information they have, their ability to process and apply the information, and the time they have to take action. It is important to consider how to make sure the learner has the right amount of information in an easily processed format at the right moment. | The learner is completing the module at the moment in which the learner needs the information (i.e. when they have an assignment to complete). The learner is therefore applying and actioning the information as they learn it. The information in the module is laid out in the order in which it is needed to write an essay (i.e. when the student is planning their essay, the module is teaching them about out to create a document outline) |

| The Framing Effect Changing how we receive information changes our decisions | Referencing is framed in a negative light noting the severe consequences of getting it wrong rather than the benefits of getting it right. | The module teaches referencing in the context of building credibility. The module explains that using SMEs adds weight to the students own arguments, resulting in potentially better grades. The module does not talk about the consequences of plagiarism but instead frames referencing as a tool to make the student’s life easier. |

| Simplification Theory We are more likely to act on a message if it is easy to understand | This could be a useful tool to teach students to utilise themselves, as being able to clearly and concisely discuss the work of an SME demonstrates a sound understanding of a topic | The module starts teaching the learner the 3 key questions of any piece of writing (Who is my audience?, What is the purpose of my document? What points are needed to get my audience to the desired outcome?). The student is taught that answering these three questions is the bedrock on which the rest of the assignment is based. |

| The Messenger Effect We are more likely to act on information that we get from an expert in the field | This could be a useful tool to teach students to utilise themselves, as properly acknowledging an SME who supports their argument gives greater weight to their assignment and potentially increases their grades. | The Messenger Effect is taught to the students in two sections - in how to build credibility in their own writing, and in how to identify and judge a source's credibility. This is done through as simple pneumonic which the student then practises on their end of module assignment. |

Table 1 : Behavioural Science concepts and how the Writing Skills module addressed them

Demographic data of the pilot group

The demographics of the 21 students discussed in this paper are:

- All based in Ireland

- All taken same reskilling course at the same time.

- 9 female; 12 male

- 8<40 years; 13>40 years

- 12 employed; 9 unemployed

- 11 have Level 6 qualification or lower; 10 have Level 7 qualification or higher

Students came from a range of other industries including food and beverage, finance, administration, healthcare, and construction.

All received Irish Government funding through a reskilling initiative – where the Government paid either 90% or 100% of their course fees.

The reskilling programmes have been delivered online for over 10 years and, as a result, programme delivery was not impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic or the associated social distancing requirements. The programmes are all designed to transition experienced workers from other industries into the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device manufacturing industry.

Data from the Pilot Group

Overview of Data Processing:

The data gathered for this paper is quantitative. The limitations of quantitative studies – as being potentially statistically relevant due to large data sets, while being humanly irrelevant, missing the contextual details surrounding the results – are acknowledged.

The data for this paper was gathered directly by the private training provider. Data was processed for ease of reading into bar and scatter graphs. For ease of interpretation, the data has been grouped into Pass grades (40%-54%), Merit grades (55%-69%) and Distinction (>70%). Plagiarism scores were classified into two groups – low (<10%) and high (>10%).

The data will now be reviewed to see what can be concluded regarding the effectiveness of the writing skills module.

Tabular Overview of the Results from the Pilot Group:

Table 2, shows the number of students in each of the 3 grade boundaries (pass, merit, distinction) for each of the modules (non-academically accredited module and academically accredited module)

| Pas | Merit | Distinction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-academically Accredited Module Grade | 2 | 16 | 3 |

| Academically Accredited Module Grade | 1 | 10 | 10 |

Table 2 : Compare Grades Before & After (Academically Accredited with Non-Academically Accredited (Overall))

From Table 2, it can be observed that there was a movement of 7 students upwords from one grade boundary to the next after completion of the writing skills module:

- Before completing the writing skills module, 3 of the students achieved a distinction grade

- After completing the writing skills module, 10 of the students achieved a distinction grade

Table 3 shows the number of students who had either low plagiarism (<10%) or high plagiarism (>10%) for each of the two modules.

| Low | High | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Academically Accredited Plagiarism Score | 14 | 7 |

| Academically Accredited Plagiarism Score | 18 | 3 |

Table 3 : Compare Plagiarism Before & After (Academically Accredited with Non-Academically Accredited (Overall))

From Table 3, it can be observed that there was a shift downward from high plagiarism to low plagiarism after completing the writing skills module:

- Before completing the writing skills module, 7 of the students had a high plagiarism score

- After completing the writing skills module, 3 students had a high plagiarism score.

Overall, this set of tables show an interesting reaction from the students to the positive messaging environment in the module, with a number receiving an increase in grades, showing that a better quality work was submitted after completing the writing skills module.

Graphical Overview of the Results from the Pilot Group:

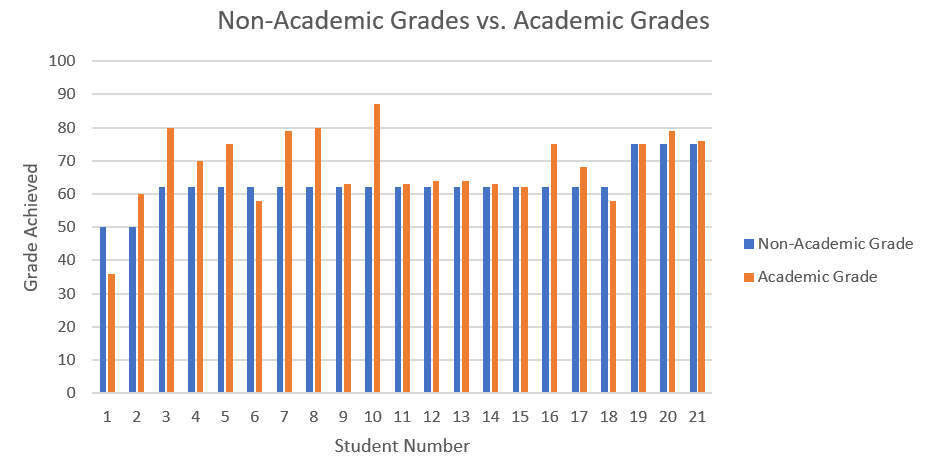

Figure 1, compares each individual student in the pilot group and their grade for each of the modules (non-academically accredited module and academically accredited module).

The blue bar represents the grade the student received on the non-academically accredited module (before taking the writing course). The orange bar represents the grade the student received on the academically accredited module (after taking the writing course).

Figure 1 : Compare Grades before & after by Student

From Figure 1, it can be observed that 33% (7) of students move up a grade boundary after completing the writing skills module.

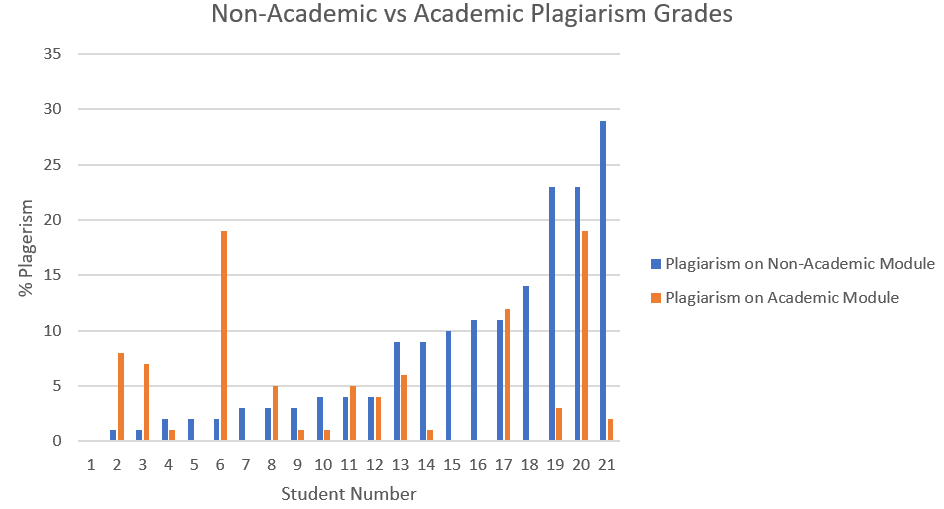

Figure 2, compares each individual student in the pilot group and their plagiarism scores for each of the modules (non-academically accredited module and academically accredited module).

From Figure 2, it can be observed that 66% (14) of students showed a decrease in their plagiarism score after completing the writing skills module, with half of these, reducing their plagiarism by more than 5%.

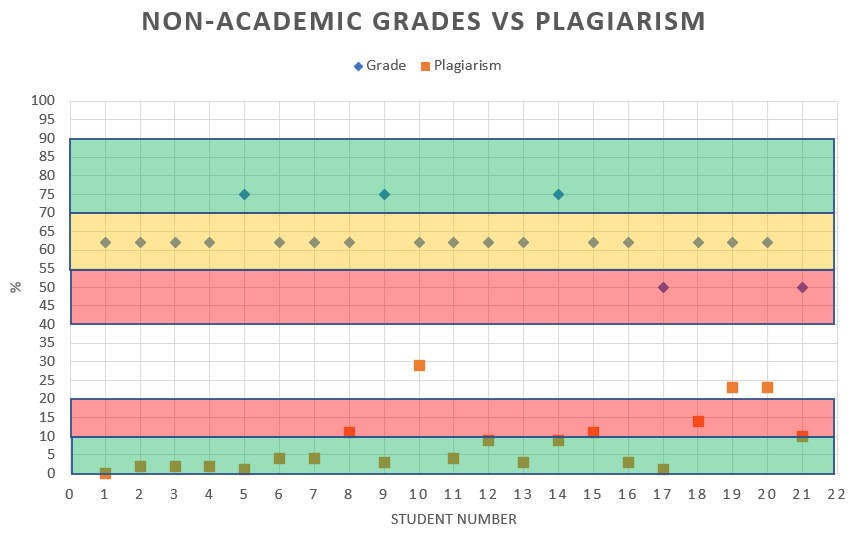

Figure 3, shows the grades achieved by each student in the pilot group, in comparison to their plagiarism score for the non academically accredited module (which was completed before the writing skills module).

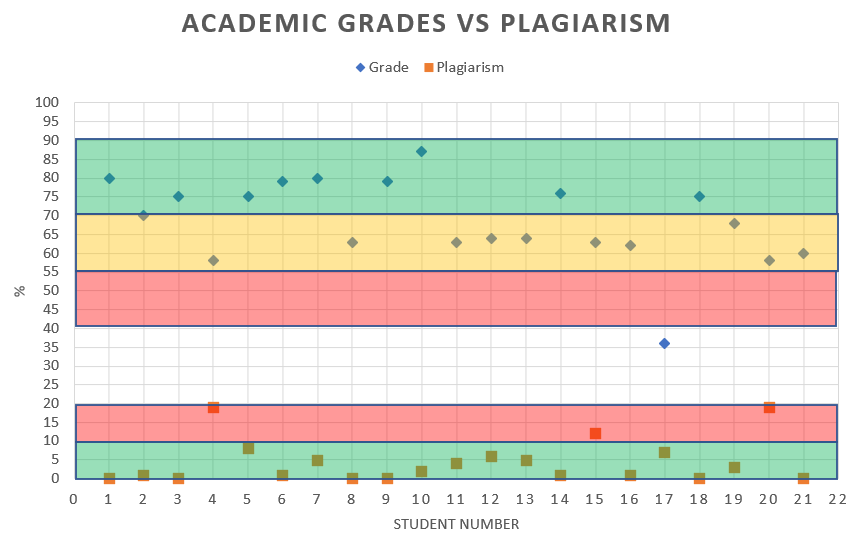

Figure 4, shows the grades achieved by each student in the pilot group, in comparison to their plagiarism score for the academically accredited module (whose assignment was completed in conjunction with the writing skills module).

For the Figures 3, and 4 below, please note:

- The green highlighted area at the bottom of the graph shows the students who had a low plagiarism score.

- The red highlighted area at the bottom of the graph shows the students who had a high plagiarism score.

- The red highlighted area in the middle of the graph shows the students who achieved a Pass grade.

- The yellow section in the middle of the graph shows the students who achieved a Merit grade.

- The green section at the top of the graph shows the students who achieved a Distinction grade.

Figures 3 & 4 : Compare Plagiarism Scores Vs Grade by Student

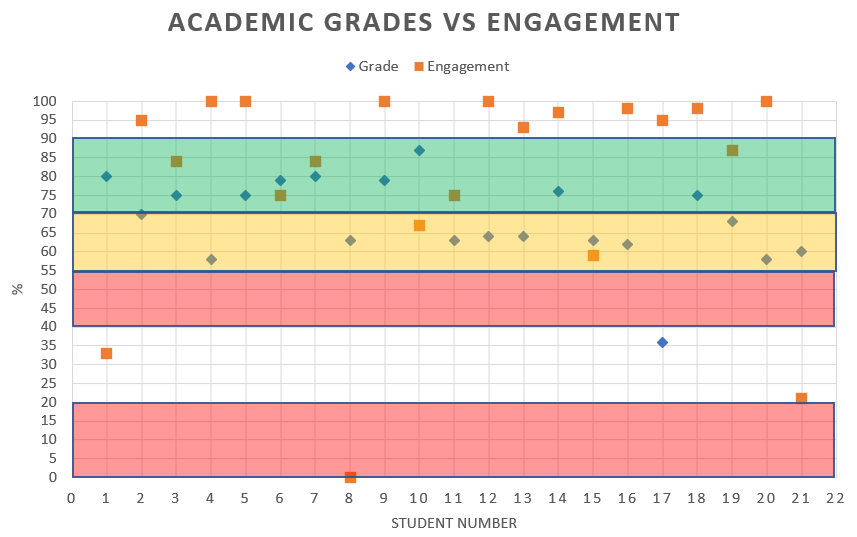

Figure 5 shows each student in the pilot group in comparison to what percentage of the writing skills module tasks they engaged with, and what their academically accredited module grade was. Please note that:

- The red highlighted section at the bottom of the graph shows low engagement

- The yellow highlighted in the middle of the graph shows a medium engagement

- The light green highlighted section towards the top of the graphs shows high engagement

Figure 5 : Compare Engagement with Writing Course with Grade After by Student

In summary, the graphical overview of Fig 1 to Fig 5 shows the following:

- 33% of students move up a grade boundary after completing the writing skills module.

- 66% of students showed a decrease in their plagiarism score after completing the writing skills module.

- The relationship between Plagiarism and assignment Grade achieved indicates that students with high plagiarism (>10%) do not achieve Distinction grades

- The relationship between Engagement with the writing skills module, and the assignment Grade achieved indicates that students with low engagement (<20%) do not achieve Distinction grades.

- Overall, there was a better quality of work submitted after completing the writing skills module as demonstrated in the change on a student by student basis in module grades.

Conclusion

The key findings from this small pilot group confirmed the initial hypotheses from the previous research. These experienced workers, when given a writing skills course developed around behavioural science theories and positive messaging, increased their grades and reduced their plagiarism scores relative to their previous assignment. Whilst these findings are not conclusive, they are a positive step in the right direction to finding alternative messaging for reducing plagiarism scores in an online environment.

- The overall outcomes of the research project are significant, as they surface the possibility of a new approach using Behavioral Science theories that could do more than just catch plagiarism, it could also improve the quality of assignments, the confidence of the students, and reduce the workload of the lecturers.

- A post-COVID world will not revert to purely classroom based teaching anymore, and therefore plagiarism in an online environment and strategies for mitigating it, will become a central element of every university’s quality standards

- Research into this area is at the leading edge of the field, and this project has a unique way of looking at the problem by using the analytical lens of behavioural science.

The next step in this research will be to expand to a larger and more diverse pool of students and study the robustness of the model at a larger scale.

Conference Presentation

These findings have been presented at the EDULearn 2021 conference in Spain.

Bibliography:

[1] Colvin Clark, R. (2010). Evidence-based Training Methods. Alexandria: ASTD Press.

[2] Cirigliano, Gustavo (1996) ‘Stages of Analysis in Comparative Education’, Comparative Education Review, 10(1),

[3] Creaner, Gerard (2015) ‘The Challenge of Delivering CPD Training for the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico within differing policies for a Knowledge Based Economy’ , RWL 9 Conference on Research Work Learning, Singapore, 2015 Volume 1, Part 3, pg 1171 – 1191

[4] Creaner, Gerard (2019) ‘Harnessing the Potential of Online Learning to Build Effective & Sustainable Lifelong Learning Frameworks: Case Studies from Ireland and Singapore’, ICDE World Conference on Online Learning, Ireland, 2019, Volume 1, Part 1, pg 128-145

[5] Dirksen, J. (2016). Design for How People Learn. 2nd Edition. USA: New Riders.

[6] Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D., & Vlaev, I. (2010). MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy. London, UK: Cabinet Office.

[7] Ellsberg, D. (1961). Risk, ambiguity, and the savage axioms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 75(4), 643-669.

[8] Halpern, David. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How small changes can make a big difference. Penguin Random House: United Kingdom

[9] Jones, P.E (1971). Comparative Education: Purpose and Method. University of Queensland Press: St. Lucia, Queensland

[10] Jung. D. (2019, March 19). Nudge action: Overcoming decision inertia in financial planning tools. Behavioraleconomics.com. Retrieved from https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/nudge-action-overcoming-decision-inertia-in-financial-planning-tools/.

[11] Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134.

[12] Madrian, B., & Shea, D. (2001). The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1149-1187.

[13] Mazzoni, G., & Vannucci, M. (2007). Hindsight bias, the misinformation effect, and false autobiographical memories. Social Cognition, 25(1), 203-220.

[14] Robson, Colin (2011). Real World Research 3rd Edition. Wiley: United Kingdom

[15] Rooney, Pauline (2005) ‘Researching from the Inside – Does it Compromise Validity’, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2005, Dublin

[16] Samson, Alain (2020) ”, The Behavioural Economics Guide 2020, 1(1), pp.

[17] Shields, Patricia; Rangarajan, Nanhini (2013). A Playbook for Research Methods: Integrating Conceptual Frameworks and Project Management. New Forums Press: United States of America

[18] Simon, Herbert (1955) ‘ A Behavioural Model of Rational Choice’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1955, Volume 69, Pg 98-118

[19] Stringer, Ernest (1996) ‘Action Research: A Handbook for Practitioners’, Sage Publications: United States of America

[20] Stolovitch, H. and Keeps, J. (2011). Telling Ain’t Training. 2nd Edition. Alexandria: ASTD Press.

[21] Sullivan, L. E. (2009). The SAGE glossary of the social and behavioral sciences. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE

[22] Thaler, Richard H & Sunstein, Cass R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press: United States of America

[23] Thaler, Richard H. (2015) Misbehaving: The making of Behavioural Economics. W. W. Norton & Company: United States of America

[24] Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science (New Series), 185, 1124-1131.

[25] Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129-140

Further Reading

This is part of a series of papers in the area of Academic Writing and Plagiarism.

You might also be interested in: