Plagiarism in Online Learning

By Gerard Creaner and Sinead Creaner

Publication Date: August 2020

This paper was presented at The 14th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics (IMSCI) 2020

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read):

Abstract

Many universities are facing the prospect of a significant increase in online teaching and assessment for the coming 2020-21 academic year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. On-campus, in-person delivery and assessment methods are often transposed to an online environment with little modification. This does not always work.

This paper looks at the experience and effectiveness of implementing a standard plagiarism awareness campaign within an online learning environment. It uses the analytical lens of behavioural science to examine the results (where the plagiarism scores for almost 20% of the adult learners were High due to poor referencing abilities) with a view to reducing these scores.

The data set has been gathered over a two-year period with 275 adult learners, coming from a variety of educational and employment backgrounds, with 5 to 25 years of work experience. All were exposed to the same lessons on plagiarism and referencing.

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

This presented the key question: How can the poor referencing abilities of otherwise capable learners be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring?

The analytical lens of behavioural science theories (in particular Bounded Rationality and the Framing Effect) suggest some explanations for the poor referencing abilities of otherwise capable learners. Likewise, Nudge Theory, Messenger Effect and Simplification suggest opportunities for insight into how to motivate learners to produce work with lower plagiarism scores.

The key outcome is the suggestion of the need for further research into creating a positive environment for learners to explore referencing and building more credible arguments through the proper use of Subject Matter Experts (SME) opinions that support their own, rather than the current situation where referencing is seen as a box-ticking exercise that results in punishment if not done correctly.

Keywords: Online Learning, Referencing, Behavioural Science, Online Assessment, Plagiarism, Adult Learners.

Introduction

Following the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent social distancing measures implemented by governments, research into online learning has never been more relevant for universities. It is widely assumed that the referencing and plagiarism strategies developed for on- campus, in-person delivery and assessment of courses can just be transposed to an online environment. This may not be true. This paper examines one private training provider’s reflections on the effect of implementing best practice for referencing and plagiarism amongst adult learners who were studying in an online environment.

The private training provider in question reskills experienced workers from other industries into the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. These vocational education (VE) programmes are delivered to experienced workers with five to 25 years’ work experience, who are returning to employment or changing their careers, coming from a variety of education and work experience backgrounds.

The subject of referencing and plagiarism has been extensively studied from the perspective of academic writing. Selemani, Chawinga & Dube (Selemani et al, 2018), for example, suggested that despite a conceptual awareness of the topic of plagiarism, learners lack the understanding to take this knowledge and implement it. They also noted that the most common forms of plagiarism were a lack of proper acknowledgment when paraphrasing and summarizing. Conclusions and recommendations suggested that implementing awareness campaigns covering the basics of referencing and the negative consequences of breaking these rules, will resolve the issue with the majority of culprits. This thinking reflects current best practice.

This paper looks to assess the success of the implementation of a best-practice standard awareness campaign for referencing and plagiarism. The paper will also look for potential areas of improvement in light of recent suggestion from Dr. Zeljana Bašić (Bašić, 2019) that significant changes need to be implemented within academic environments to foster a positive climate within which learners can understand their responsibilities when writing.

Conceptual Framework

This paper is broadly practitioner research using case studies as illustrative of real-world phenomena. The methodology for comparison draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1964).

In Bereday’s model, ‘everyday’ comparability is distinguished from socially-scientific or laboratory methods. The everyday comparability approach fits with individualistic practitioner research in that it favours establishing relations between observable facts, noting similarities and graded differences, drawing out universal observations and criteria, and ranking them in terms of similarities and differences.

In everyday comparability, the view is subjectively from within and deliberately without perspectives detachment. It focuses on group interests, social tensions, impact factors and collective beliefs, patterns, and behaviours as experienced by the authors.

In terms of analytical steps, this paper uses Bereday’s four stages as illustrated by Jones (Jones, 1971), as follows:

- Stage 1: Description of each case using a common approach to present facts

- Stage 2: Interpretation of the facts in each case using knowledge other than the authors

- Stage 3: Juxtaposition for preliminary comparison using a set of relevant criteria

- Stage 4: Simultaneous comparison, emergence of conclusions and hypotheses

The perspective in this paper is the authors’ own as the private training provider of vocational education programmes, mindful of the particular risks of insider research (Rooney, 2005).

Current Practice

The assignment grades and associated plagiarism scores of 275 adult learners were measured over a two-year period (2017-2019). Half of these adult learners studied a non-academically accredited module and the other half- completed an academically accredited module at an undergraduate level.

Both groups received the same standard awareness campaign on plagiarism. This took the form of a two- page guide covering what plagiarism is, how to avoid it, and why it is serious. The learners were also advised to contact a member of staff if they had questions or queries on plagiarism and how to avoid it. This guide was presented at the top of each course page displayed to the learners for the entire duration of their studies. It was also re-issued via email each time a written assignment was given to them. Learners were further motivated by being reminded that as they were entering a life-critical industry where the safety of patients relies on their honesty and adherence to strict protocols, plagiarism (unintentional or not) raised a significant red flag on their suitability to work in such an industry.

Once assignments were submitted, the lecturers established a grade for them. All the assignments were processed through the same standard plagiarism software (Grammarly), to establish a plagiarism score. The plagiarism software also identified which sections of the assignment were problematic, and where this information could be found online. The lecturer could then launch an investigation if it was deemed necessary.

The investigation looks to establish whether the issue was due to malicious plagiarism or poor referencing. If the assignment conclusions were deemed to be the learner’s own, the assignment could pass, despite poor referencing. As experienced lecturers, markers could typically identify where malicious plagiarism existed, so the plagiarism software performed two key actions:

- It confirmed the lecturer’s suspicions with evidence. This allowed the lecturer to discuss problematic sections and decide whether conclusions were the learner’s own.

- It gave a quantitative score by which all the assignments could be objectively compared.

Research Findings

The data gathered for this paper is quantitative. The limitations of quantitative studies – as potentially statistically relevant due to large data sets while being humanly irrelevant, missing the contextual details surrounding the results – are acknowledged. However, in this case, in the straddling between insider-actor mode and outsider-observer mode (Robson, 2011), and due to the research question in hand, the research generated provides a large enough basis on which to build observations.

For the purposes of this paper, a modified growth-share matrix (more commonly known as a BCG matrix) was used. This modified growth-share matrix divides results into 6-quadrants and shows the grades achieved (Pass, Merit, or Distinction) and the plagiarism score (High or Low) for each assignment.

The data for this paper was gathered directly by the training provider using tools including Grammarly. The data has been processed for ease of reading using Microsoft Excel. For data organization, interpretation, analysis and presentation, the total answers have been processed into descriptive statistics.

The achieved grades are based on Pass and Distinction being one standard deviation either side of the mean. The plagiarism score is based on High being one standard deviation above the mean, with Low being assigned to all other plagiarism scores. A High plagiarism score flagged an assignment for investigation. Failing assignments with malicious plagiarism have been excluded, so learners with High plagiarism scores have all been investigated and the conclusions of assignments were deemed to be the learner’s own. High scores are therefore due to poor referencing.

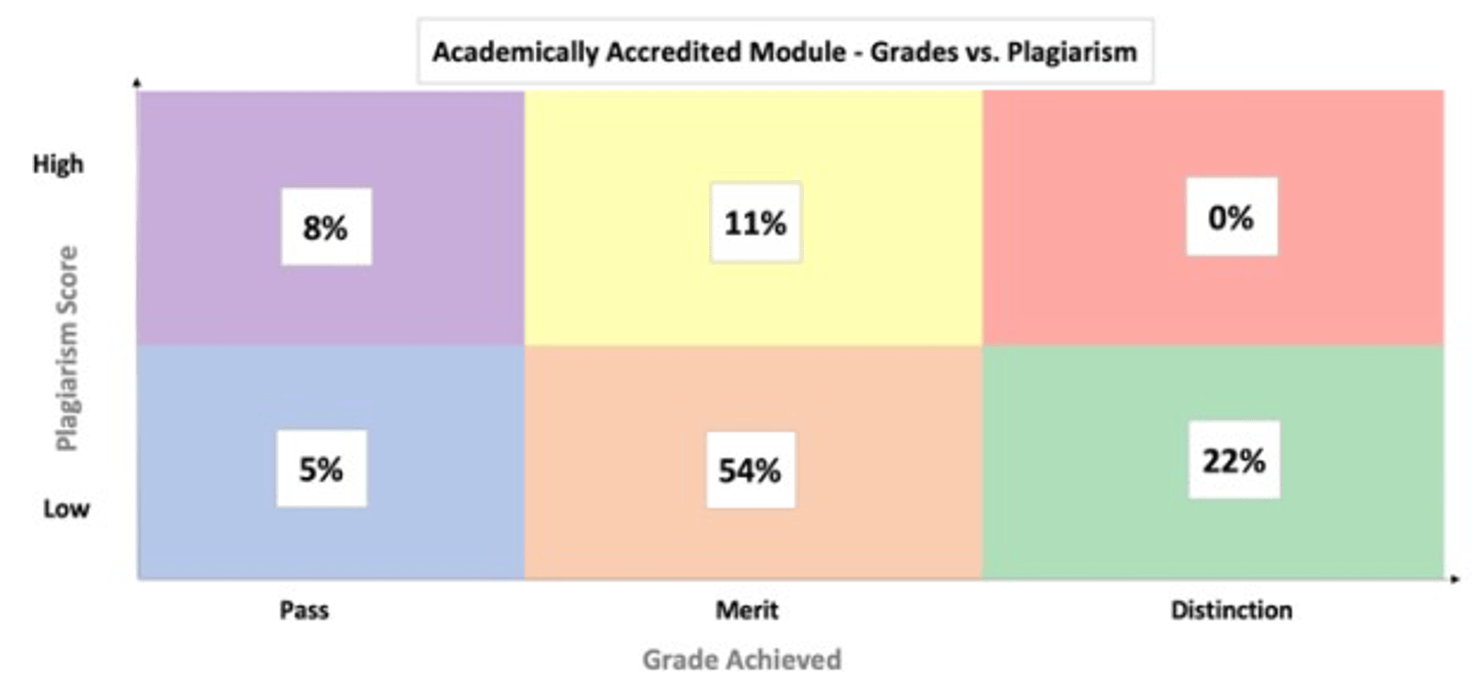

The growth-share matrix plotting assignment grade and plagiarism score for the academic module can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Modified BCG matrix of grades achieved (Pass, Merit, Distinction) and the associated plagiarism score (Low or High) for the academically accredited module.

There are 2 key points to be considered from this:

- 19% of adult learners had a High plagiarism score

- 100% of adult learners who achieved a Distinction grade had a Low plagiarism score

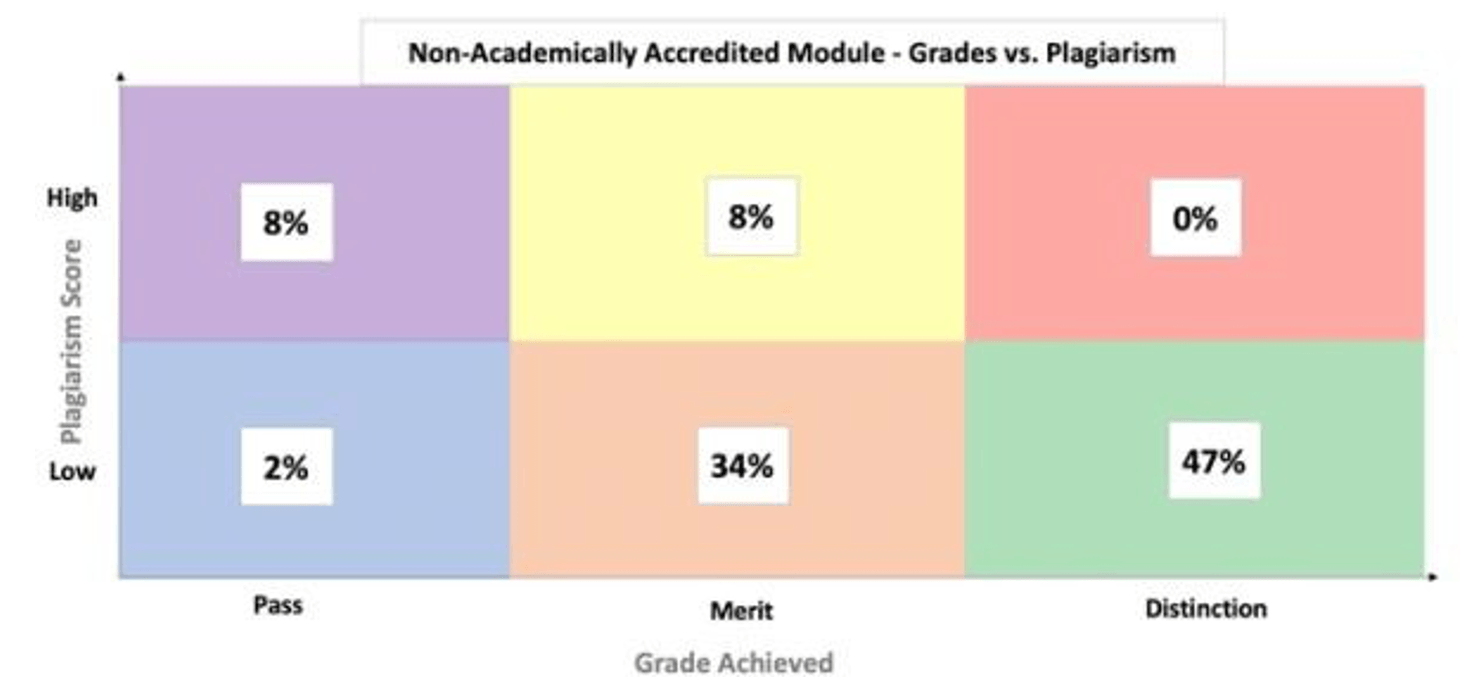

The growth-share matrix plotting assignment grade and plagiarism score for the non-academically accredited module can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Modified BCG matrix of grades achieved (Pass, Merit, Distinction) and the associated plagiarism score (Low or High) for the non-academically accredited module.

There are 2 key points to be considered from this:

- 16% of adult learners had a High plagiarism score

- 100% of adult learners who achieved a Distinction grade had a Low plagiarism score

The similarity in results between the two modules suggests that for future studies, the insights generated from non-academically accredited modules can be applied to academically accredited ones and vice versa.

This analysis presents the question: How can the poor referencing abilities of otherwise capable learners be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring?

Theoretical Framework for Analysis

Previous research from this private training provider was reported at the Research Work Learning Conference 2015 in Singapore and at the ICDE World Conference on Online Learning 2019 (Creaner, 2019). This work found the lens of Behavioural Economics to be particularly useful to interpret the decisions of learners in an online environment. This current analysis further builds on those ideas, and looks to specifically understand and improve the adult learner’s approach to plagiarism and referencing.

Behavioural science is the study of human motivation, decision making, and actions. It tries to understand how people interpret information; why they make the decisions they do when faced with multiple options; and, ultimately, why people behave the way they do.

The analytical lens of behavioural science theories (in particular Bounded Rationality and the Framing Effect)

suggest some explanations for the poor referencing abilities of otherwise able learners. Likewise, Nudge Theory, Messenger Effect and Simplification could also give insights into how to motivate learners to produce work with lower plagiarism scores.

Bounded Rationality:

Herbert A. Simon is seen as the founder of modern behavioural science, after winning the Noble Prize for Economics in 1978 for his theory of Bounded Rationality. He demonstrated that humans make decisions to achieve a satisfactory outcome, rather than an optimal one because our decisions are made on the knowledge we have, our ability to process this knowledge, and the amount of time we have to make the decision (Simon, 1955). This suggests that learner’s abilities to implement the knowledge they receive on plagiarism and referencing is dependent on these three factors.

The Framing Effect:

The Framing Effect, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1978), tells us that the way information is presented to us changes how we interpret it. Tversky and Kahneman conducted experiments around how to re- frame the same information in a positive or negative light, and analysed how this framing would ultimately affect the individuals’ decision. They concluded that changing how information is presented, also changes the decisions made by individuals (Kahneman, 2012)

This is of particular relevance to this analysis, as a change in the best practice awareness campaigns around plagiarism, could ultimately change the way adult learners understand their responsibilities around referencing, plagiarism, and academic writing. It also aligns with the conclusions of Dr. Bašić (Bašić, 2019) that significant changes need to be implemented within academic environments to foster a positive climate within which students can understand their responsibilities when writing.

Nudge Theory:

Developed by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in 2008, Nudge Theory suggests that since framing of a choice can significantly change the decision that people make, “choice architecture” can help people make “better” choices for themselves (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Nudge theory has now been adopted by several governments, including the UK Government’s Behavioural Insights Team (Halpern, 2015).

Simplification:

The Simplification theory, developed by the U.K.’s Behavioural Insights Team, tells us that we are more likely to act on a message if it is easy to understand (BE Guide, 2019). The more complicated you make things, the less likely people are to carry them out. Delivery of information should focus on clarity and conciseness.

The Messenger Effect:

The Messenger Effect, which was also developed by the U.K.’s Behavioural Insights Team, further builds on the behavioural science theories of Simon, Kahneman and Tversky. The Messenger Effect means we are more likely to act on information that we get from an expert in the field (BE Guide, 2019).

It is hypothesised that nudges utilising the Simplification and Messenger effects could also give insights into how to motivate learners to produce work with lower plagiarism scores.

Analysis and Discussion

A simultaneous comparison is now conducted for the emergence of conclusions and hypotheses in tabular form below (Stage 4 Bereday). Table 1 (below) shows the analytical lens of behavioural science (Bounded Rationality & the Framing Effect), laid over the question “How can the poor referencing abilities of otherwise able learners be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring?”, with the final column examining possible nudges for further research.

| Behavioural Science Lens | How can the poor referencing abilities of otherwise capable learners be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring? | Ideas for Further Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bounded Rationality: Suggest that humans are satisficers, not optimisers | Adult learners with High Plagiarism scores show stronger satisficer tendencies than optimizer abilities. Otherwise able learners with high plagiarism scores due to poor referencing abilities are impacted by the amount of information they have, their ability to process/apply this information and the time they have to action it. When looking to lower the plagiarism scores, this should be considered. Particularly how to make sure the learner has the right amount of information in an easily-processed format. | When looking to change the behaviour of learners, an area for further research would be to implement nudges around the theories of: Simplification - being able to clearly and concisely discuss the work of an SME in your own words demonstrates a sound understanding of the topic. The Messenger Effect - showing that properly acknowledging an SME who supports their argument gives greater weight to their own assignment and potentially increases their grades. |

| The Framing Effect: Changing how we receive information changes our decisions | Currently, the negative messaging of “you’ll be punished for plagiarizing” still resulted in almost 20% of otherwise capable learners having high plagiarism scores due to poor referencing abilities. At the moment, when referencing an SME, a standard plagiarism awareness campaign focuses on the negative message, and then moves directly into a discussion on detail of the different referencing styles. When looking to change this behaviour of learners, it may be worthwhile exploring the benefits of having positive messaging on the advantages of referencing. For example, properly referencing the opinions of SMEs will add weight to the learner’s own argument, resulting in more credible arguments and lower plagiarism scores. |

Table 1: Understanding how the poor referencing abilities of otherwise able learners can be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring, through the lens of bounded rationality and framing effect, and suggesting possible nudges for further research.

Areas of Future Study

The Bereday Table (Stage 4) demonstrates how the lens of behavioural science could move adult learners towards a better implementation of referencing as a way to test their knowledge, demonstrate their competence, and build a more credible argument for their writing, rather than a box-ticking exercise that results in punishment for plagiarism if not done successfully.

The current best practice which uses negative messaging to stress the downside of poor referencing in assignments and assessments, results in a significant number (almost 20%) of otherwise capable adult learners not embracing the potential upside of referencing SME’s opinions to strengthen their own arguments and potentially increase their grades, as they are entirely focused on the messaging of “you’ll be punished for plagiarism”.

For lecturers, the current messaging results in unnecessary time and effort being spent investigating and documenting High plagiarism scores which are ultimately not deemed to be the result of malicious plagiarism, but simply poor referencing abilities.

The lecturer and the learner both have the potential to benefit from further research into an improved approach.

There are two proposed areas for further study:

- Nudges that utilise Simplification Theory. Being able to clearly and concisely discuss the work of an SME in your own words demonstrates a sound understanding of the topic. Paraphrasing and summarising (a key weakness according to Selemani, Chawinga & Dube (Selemani et al, 2018)) requires a deep understanding of the topic and the ability to be clear and concise when referencing an SME’s opinion is a key skill. This could be framed as a useful check for learners to self-assess their own understanding.

- Nudges that utilise Messenger Effect. Showing that properly acknowledging an SME who supports their argument gives greater weight to their own assignment and potentially increases their grades.

Conclusion

This paper examined the plagiarism scores of adult learners studying online programmes. It was shown that almost 20% of adult learners had a High plagiarism score and that 100% of adult learners who achieved a Distinction grade had a Low plagiarism score.

Since those demonstrating malicious plagiarism had been excluded from the study, it can be concluded that these figures were a result of poor referencing skills. This resulted in learners with poorly supported arguments, and likely sub-optimal grades, as well as lecturers dealing with an avoidable workload of investigation and documentation of these plagiarism scores.

This presented the key question: How can the poor referencing abilities of otherwise capable learners be addressed to produce work that is Low plagiarism scoring?

Using the analytical lens of behavioural science, these results were explained. This led to the idea of creating a positive environment for learners to explore referencing and building more credible arguments through the proper use of SME opinions that support their own, rather than the current situation where referencing is seen as a box- ticking exercise that results in punishment if not done correctly.

The paper then suggested Nudge Theory, and in particular nudges that utilise the Simplification and Messenger Effects, as a possible area of future study. It was concluded that research into this area could potentially be of great benefit to both the lecturer and the learner.

This paper is of particular relevance at the moment when entering the 2020-21 academic year. A post-COVID world will require more teaching, assessments, and assignments to be completed within an online environment. Examining the current frameworks around referencing and plagiarism for their fit in an online environment has never been more necessary.

Conference Presentation

These findings have been presented at the IMSCI 2020 in Florida, USA.

References

[1] Bašić, Željana et al. “Attitudes and Knowledge About Plagiarism Among University Students: Cross-Sectional Survey at the University of Split, Croatia.” Science and engineering ethics vol. 25,5 (2019): 1467-1483.

[2] Cirigliano, Gustavo (1996) ‘Stages of Analysis in Comparative Education’, Comparative Education Review, 10(1),

[3] Creaner, Gerard (2015) ‘The Challenge of Delivering CPD Training for the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico within differing policies for a Knowledge Based Economy’ , RWL 9 Conference on Research Work Learning, Singapore, 2015 Volume 1,

Part 3, pg 1171 – 1191

[4] Creaner, Gerard (2019) ‘Harnessing the Potential of Online Learning to Build Effective & Sustainable Lifelong Learning Frameworks: Case Studies from Ireland and Singapore’, ICDE World Conference on Online Learning, Ireland, 2019, Volume 1, Part 1, pg 128-145

[5] Halpern, David. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How small changes can make a big difference. United Kingdom: Penguin Random House

[6] Jones, P.E (1971). Comparative Education: Purpose and Method. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press

[7] Kahneman, Daniel (2012). Thinking Fast and Slow. United Kingdom: Penguin Random House

[8] Robson, Colin (2011). Real World Research 3rd Edition. United Kingdom: Wiley

[9] Rooney, Pauline (2005) ‘Researching from the Inside – Does it Compromise Validity’, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2005, Dublin

[10] Samson, Alain (2020) ”, The Behavioural Economics Guide 2020, Volume 1(1), pp.

[11] Selemani, A., Chawinga, W.D. & Dube, G. Why do postgraduate students commit plagiarism? An empirical study. Int J Educ Integr 14, 7 (2018).

[12] Shields, Patricia; Rangarajan, Nanhini (2013). A Playbook for Research Methods: Integrating Conceptual Frameworks and Project Management. United States of America: New Forums Press

[13] Simon, Herbert (1955) ‘ A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1955, Volume 69, Pg 98-118

[14] Thaler, Richard H & Sunstein, Cass R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. United States of America: Yale University Press

[15] Thaler, Richard H. (2015) Misbehaving: The making of Behavioural Economics. United States of America: W.W. Norton & Company

Further Reading

This is part of a series of papers in the area of Academic Writing and Plagiarism.

You might also be interested in: