Lifelong Learning and the Knowledge Economy (RWL 2015)

The Challenge of Delivering CPD Training for the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico with Differing Policies for a Knowledge-Based Economy

By Gerard Creaner

Publication Date: November 2015

This paper was presented at the 9th Research Work & Learning Conference (RWL) 2015

Table of Contents (click to the section you would like to read)

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Research Approach and Structure of the Paper

- The Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Context

- Knowledge Economy and Lifelong Learning in Three Locations

- The Irish Case

- The Singapore Case

- The Puerto Rico Case

- Cross-Comparison of Cases

- Implications for Private Training Providers from the Three Cases

- Concluding Comments

- Bibliography

- Further Reading

Abstract

This paper offers an analysis of the author’s ten-year experience as a private training provider delivering technical continuing professional development (CPD) training for the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector in Ireland since 2005, Singapore since 2008 and Puerto Rico since 2014.

This training was delivered both to employees within the pharmaceutical manufacturing companies and to experienced workers from other sectors who wished to make a career change into this highly regulated sector. Negotiation, development and delivery of training in each of the three locations highlighted the significance of how local economic development policies for the sector are shaped both by local understandings of a knowledge-based economy and by the requirements of the international drug regulatory authorities.

The research is essentially a comparison of three cases using Bereday’s four stages of description, interpretation, juxtaposition and comparison as both methodology and structure. Data for the paper were drawn from relevant economic policy and employment literature for each of the three sites, from relevant pharmaceutical sector regulations, and from original documentation in relation to development and delivery of the CPD programmes concerned.

The findings in this paper give an insight into dynamics of CPD provision as a function of fluctuations in national economic conditions/wellbeing of a nation. It questions the true relevance of broad- based lifelong learning initiatives in creating a sustainable knowledge-based economy for a hi-tech industry, if such initiatives are abandoned at the first sign of economic difficulty.

The paper makes observations about the long-term impact of tensions for the development of a knowledge-based economy for the provision of learning in the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector and discusses specific recommendations based on my insights. These have been gained during this ten year analysis, primarily from Ireland and Singapore: in Puerto Rico only the Government negotiations and approval process has been completed to date.

Insights presented in this paper have come from training and educating 1500 workers, interfacing and negotiating with numerous Government agencies, and meeting with fifty multinational pharmaceutical companies.

Insights include the following:

- It appears that whilst a knowledge-based economy requires the lifelong learning of its citizens in order to succeed, many technical workers are reluctant to invest

- their time and effort into technical learning programs after employment has been

- secured.

- Despite many pharmaceutical companies hiring large numbers of graduates from

- my CPD programs since 2011, they have not looked for their existing operators

- and technicians to undertake similar CPD programs.

- Whilst current theory and Government strategies supports the building of a

- knowledge-based economy through the lifelong learning of its workers, neither the employers nor the workers appear to want to invest their time and effort once the resource is hired or the job is secured.

- I question if a nation can develop a knowledge-based economy without the emotional support of its citizens and employers for lifelong learning.

- I question whether the case for legislation of lifelong learning for both companies and the workforce in certain industry sectors which could benefit a nation and its citizens should be considered.

Introduction

Periods of economic turbulence are useful instances to identify both the explicit and implicit socio-economic models at play in a given country. Long term aspirational projects which require funding during growth periods get challenged by short term critical needs during more difficult recessionary times, particularly with regard to investment in education and training. The ten year time-frame of this analysis (2005- 2015) has been a very interesting time of great economic turbulence across the world. In 2005 the East was still recovering from the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the West was still riding high in the aftermath of the dotcom-fuelled boom. Ireland was at the heights of the Celtic Tiger and the US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan was projecting continued growth in the US economy (Greenspan, 2005). It was during this recovery and expansionary stage that the three cases analysed in this paper had their genesis.

Only three years later the world was a very different place with Global Recession in the West and the associated huge job losses and contraction of economies. This recession initially impacted on the markets in Asia but they recovered quicker and more strongly than the West, led by the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) economies and China in particular (Singapore ESC, 2010) The global crisis reinforced the shift of the economic markets to Asia.

The impact of this global economic turbulence is viewed through my lens of a specialist private training provider delivering education and training solutions for the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. Government policies in place at the start of the analysis period (2005-2008) reflected long-term aspirations that countries were happy to budget for during boom times which were expected to continue.

During the middle period (2008-2011), which could be defined as ‘bust times’ on a global scale, the sustainability of the ‘boom time’ projects were challenged and the different Governments made different decisions about continuing their planned investments in a knowledge-based economy during these more difficult times.

The final time frame (2011-2015) can be referred to as moving into a period of ‘cautious growth’ during the recovery period of the world economies after the 2008 global downturn. The particular ten year timeframe of this analysis has offered a great opportunity to witness how the implementation of Government policies in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico changed due to the social and political challenges from significant fluctuations in their national economy during the three different periods of boom, bust and cautious recovery.

Research Approach and Structure of Paper

This paper is broadly practitioner research using three cases as illustrative of real world phenomena. The stance is reflexive and critical, acknowledging that the knowledge presented cannot be easily separated from the knower. As author I am in the space straddling insider-actor mode and outsider-observer mode acknowledging my involvement in both modes. The reflexivity involved is essentially introspective rather than systematic or methodological. Essentially the work falls within the genre of practitioner research on past and current activities without those activities being deliberately planned as cyclical action research. Selection of data and their interpretation within layers of analysis are as deemed meaningful and relevant by me as author (Robson, 2011).

The methodology for comparison of the three cases draws heavily on Bereday’s model of comparative styles and their predispositions (Bereday, 1966, 1967). In Bereday’s model ‘everyday’ comparability is distinguished from socially-scientific or laboratory methods. The ‘everyday’ comparability approach fits with individualistic practitioner research in that it favours establishing relations between observable facts, noting similarities and graded differences, drawing out universal observations and criteria, and ranking them in terms of similarities and differences. In everyday comparability the view is subjectively from within, and deliberately without perspectives detachment. It focuses on group interests, social tensions, impact factors and collective beliefs, patterns and behaviours as experienced by the researcher. While Bereday’s model is relatively aged it nonetheless is appropriate in this paper as a tool to structure iterations of analysis which stress the value of balanced enquiry within broad contexts. Bereday recommends illustrative comparison where data are too-imprecise for fully balanced comparison, as in the case described in this paper.

In terms of analytical steps this paper uses Bereday’s four stages as illustrated by Jones (1971 page 88) as follows:

- Stage I: Description of each case using a common approach to present facts

- Stage II: Interpretation of the facts in each case using knowledge other than the author’s

- Stage III: Juxtaposition for preliminary comparison using a set of relevant criteria

- Stage IV: Simultaneous comparison emergence of conclusions and hypotheses.

The structure of the paper follows from the methodology above. In the first part the context of the Pharmaceutical manufacturing sector is outlined and the reasons for the development of manufacturing hubs in the three countries.

In Sections 3 and 4 the cases of Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico are described in terms of the local stage of industrial development, government policies for a knowledge based economy, the contribution of lifelong learning of the workforce and the government support for the pharmaceutical industry.

The pre and post 2008 Global Economic downturn in each of the countries is examined through the lens of initiatives for CPD training programs for their workforce, driven by the different social and political consequences for each country. Sections 5 & 6 sets out the three cases in juxtaposition in tabular form as suggested by Bereday and identifies areas of convergence and divergence between the countries.

The perspective in this paper is my own as the private provider of CPD training in the three case studies, mindful of the particular risks of insider research (Rooney, 2005). To acknowledge this insider status ‘I’ and ‘we’ are used throughout.

The Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Context

The Pharmaceutical sector involves the manufacture of medicines and medical devices. These products, and the companies which manufacture them, are also referred to as Life Sciences, MedTech and BioMed in different parts of the world, as noted in the list of references for this paper. However for the purposes of clarity they will all be referred to by the single term Pharmaceutical.

Pharmaceutical companies are in the business of manufacturing safe medicines for the public at an affordable cost which does not entail excessive regulatory oversight (FDA Mar 2004). This essentially defines how the sector is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US and by other international regulatory agencies in different parts of the world, including the EMA (European Medicines Agency) in Europe. While each individual agency will have specific nuances regarding how they apply their regulations, all of them regulate the companies in their jurisdiction within the spirit of this definition. For the purposes of this paper all regulatory agencies will be referred to by the single term FDA.

To elaborate the above definition of the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector so as to better understand the basis of the CPD programmes addressed in this paper, firstly it is useful to consider what constitutes a ‘safe medicine’ and how it is determined to be safe to take. In order to confirm that a medicine is safe to use it has to be tested under controlled conditions. But if one tablet, or the contents of one vial, is tested, how does one know that the injection from another vial will do no harm and will help to effect a cure?

It is only practicably possible to test a representative portion of the medicines that are manufactured to determine that they are safe to use and so the FDA has defined a series of Quality Systems and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) to be used to also check for manufacturing compliance. If an FDA audit deems that the manufacturing has been in compliance with the GMPs and the portion of medicines tested are determined to be safe, then all of the medicines that have been manufactured are deemed to be safe and can be sold to the public.

A very extensive and onerous set of GMPs will increase the cost of manufacturing medicines in order to be in compliance with the regulations and it will also increase the efforts and time spent by the FDA to audit for compliance. High costs of compliance will result in more costly medicines for the public and fewer people being able to afford them. Hence the mandate of the FDA is to ensure the public has access to safe medicines at an affordable price not entailing excessive regulatory oversight. This in essence forms the basis of the Mission Statement for all Pharmaceutical manufacturing companies and it is the basis of the CPD programmes delivered by this training provider in three global locations, i.e. Europe (Ireland), Asia (Singapore) and America (Puerto Rico).

These three locations were chosen to deliver these CPD programmes as they are all significant pharmaceutical manufacturing hubs in this highly regulated industry, often referred to as Centres of Excellence in the promotional literature from their Government agencies (PharmaChemical Ireland, 2010).

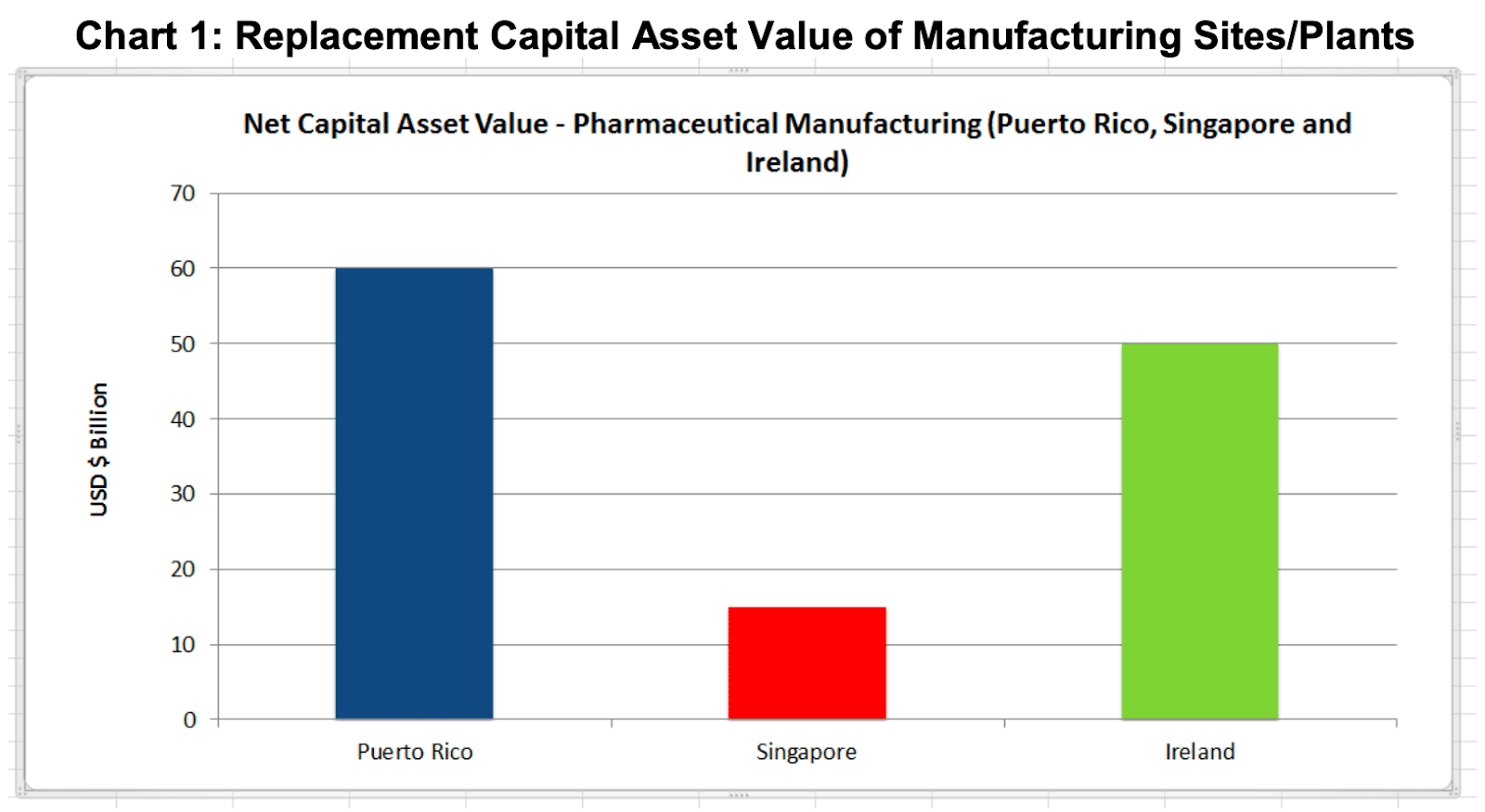

Governments compete to enter the Pharmaceutical manufacturing supply chain as it is a very stable and secure hi-tech. manufacturing sector. It generates long-term good paying jobs. Its workers have salaries in the top quartile and it supports very significant capital investments to build these manufacturing facilities. In Ireland the replacement capital asset value of its current pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities is $50 Billion and new investments underway in 2015 are valued at a further $3 Billion (IDA Ireland, 2005). Significant capital investment to a value of $60 Billion has been made in Puerto Rico since the 1960s when the first pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities were established on the island (Jones, 2006). In Singapore, significant investment only commenced in the late 1990s following a Government decision to focus on establishing pharmaceuticals as the fourth pillar of the Singapore economy. Their BioMedical Science (BMS) sector already employs 6,000-workers in pharmaceutical manufacturing and is their largest manufacturing sector generating 5% of GDP. (Singapore EDB, 2013)

Knowledge Economy and Lifelong Learning in Three Locations

The three cases analysed which are central to this paper are located in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico, all small island states with a growing dependence on knowledge-based manufacturing and services economies. All three have identified the pharmaceutical sector for economic and labour market growth and continue to invest significantly in relevant education and training and in labour market measures to support the continued growth of the sector (The Stationary Office, 2006; Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, 2014; Singapore ESC, 2010). All three use the English language in addition to local languages, have well developed education and training systems, have relatively young populations, are politically stable and strategically located on efficient and viable air and sea transport routes to potential markets.

Pharmaceutical companies have very high levels of human intervention in their manufacturing process at an operator/technician level. This workforce has predominantly a High School or non-degree 3rd level academic qualification and this frames the workforce development structures necessary for achieving Centre of Excellence status for manufacturing safe medicines. The nature of the manufacturing process requires decisions and inputs from the operators/technicians in order to move onto the next step in the process. Hence the overall process, whilst technologically complex, cannot be defined as ‘automated’ where human intervention has been eliminated, unlike other hi-tech industries. This human intervention requires that the workers be familiar with, and apply, the GMPs defined and audited by the FDA to ensure manufacturing compliance for the approval and release of safe medicines to the public.

Consistency in human interactions is difficult to achieve. The FDA records clearly shows that significant non-compliance still occurs in both large and small pharmaceutical manufacturing companies in the West, despite decades of manufacturing experience and regular FDA audits (Deloitte, 2013).

This business risk to serious quality problems from manufacturing errors has contributed to the establishment of pharmaceutical manufacturing hubs both within the US and across the world. These hubs are the locations where the industry has greatest confidence in the rigour of the manufacturing process and the ability of the workforce to manufacture in compliance with FDA regulations. A strong manufacturing quality track record is a key factor as to why Ireland, Puerto Rico and Singapore have differentiated themselves from other countries in this niche hi-tech highly regulated manufacturing environment. It is a key element of their Governments’ strategies for developing a knowledge-based economy for the benefit of their citizens and it is the basis of the training and education programmes developed by this specialist training provider.

The Irish Case

In 2005 the Irish economy was experiencing a phase of sudden economic growth. Government thinking about a knowledge-based economy was encapsulated in their seven year Strategy for Science Technology and Innovation 2006-2013. (The Stationary Office, 2006) This document contained references to improving maths and science in junior schools, doubling PhD numbers, commercialising university research and investing in mechanisms to translate knowledge into jobs and growth. Funding was made available to the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector to provide up-skilling of existing staff and re-skilling of workers looking to transition from other less dynamic sectors into this hi-tech industry.

In 2005 I formed an industry-academia partnership with the Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT) which had a lengthy track record in the science sector. A Bachelor of Science degree programme for experienced workers who wanted to make a career transition into the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector in operator/technician roles was developed using a modular, work-based learning model. This twelve module programme consisted of six industry-specific modules on the manufacture of safe medicines delivered by my private company and six modules focussed on the underpinning science associated with pharmaceuticals provided by the DIT partner and awarding body.

This industry-academia model was an innovative approach to developing a pool of talent to both satisfy a pharmaceutical company’s employment demands and also allow the Government to continue to attract more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for new manufacturing facilities into Ireland. Companies could select the numbers and sequence of modules to suit their immediate needs, seamlessly combining self- financing and state-funded learners. However, with the 2008 Global economic downturn, the Irish Government withdrew funding support and the training model diminished.

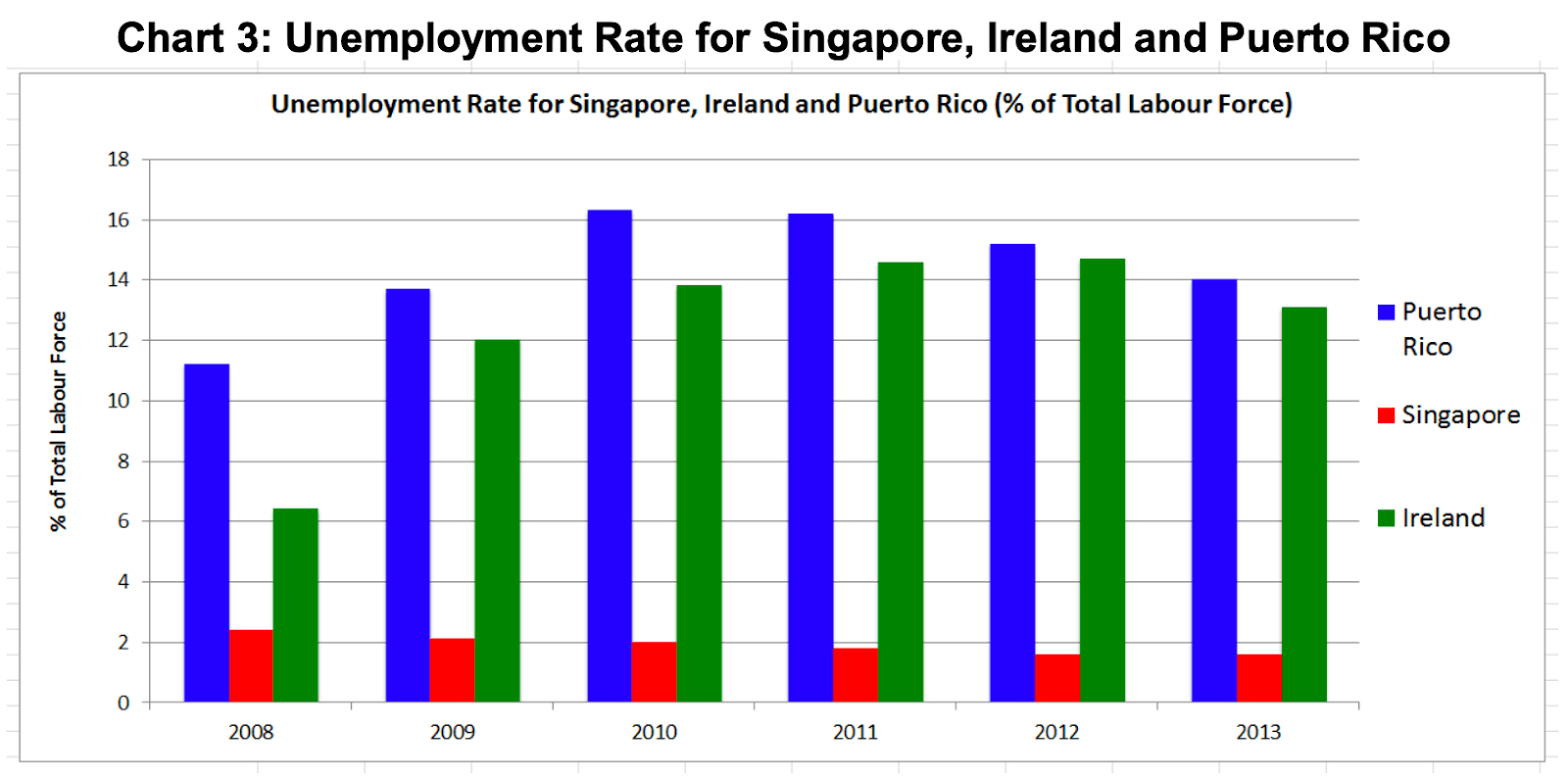

The economic downturn in Ireland resulted in 200,000 workers losing their jobs during 2008-2010, increasing unemployment levels to 15% with the associated loss of pay related tax revenues to the Government and the huge increase in social welfare unemployment payments to these retrenched workers. The social and political problems from Government cuts to services to bring financial balance back to the economy were huge. Funding for ‘aspirational’ projects from the ‘boom’ times without a quantifiable outcome in the short term was stopped, including our program.

Without Government funding workers generally did not view self-funding for re- skilling to a new industry sector as a good personal investment. The pharmaceutical companies who had benefited from the Governments initiatives during the ‘boom’ years to up-skill their workforce also did not continue these programs when the Government funding ended, preferring to train their employees with short in-house programs specific to their needs.

This questions the true relevance of such broad-based lifelong learning initiatives in creating a sustainable knowledge-based economy for a hi-tech industry, if they can be abandoned at the first sign of economic difficulty.

In Ireland, the pharmaceutical sector remained resilient to this economic downturn and continued to expand. In 2009 the Government reacted to the social and political challenges of high unemployment and shifted its focus from a co-funded general training approach to a fully funded sectoral training initiative to reengage unemployed workers into employment. Pharmaceuticals was identified as one of six sectors appropriate to absorb significant numbers of recently unemployed, skilled workers through a series of Labour Market Activation (LMA) schemes, later known under the name of Springboard (The Stationary Office, 2014).

This Government re-skilling initiative has continued through the ‘bust’ times and into the cautious recovery period to the present day. It is focussed on transitioning retrenched workers back into employment in specific industries through academically accredited industry relevant programs. Full funding for the trainees is provided and securing employment rather than an academic qualification from the program is the priority of the Springboard initiative, even though it is administered through the Higher Education Authority (HEA) and not the Department of Labour.

It is a very different model to the one that was used in the ‘boom’ times. It is focussed on much more immediate and measurable outcomes, as most programs have to be completed on a part-time basis and within one year. Programs are tendered for annually on a competitive basis (my CPD program has been funded for five consecutive years under this initiative) and a key criteria for selection is the success of past trainees in securing employment in these identified hi-tech industries which contribute to the growth of the economy.

Between 2011-2015 in excess of 1,000-workers attended my online academically accredited CPD programs under the Springboard initiative and 75% of these workers have successfully secured employment. This re-skilling model can be classified as “Train and Place” where a pool of qualified workers are trained with industry relevant knowledge, skills and qualifications and then companies draw from that pool to place them in their companies to meet a resource requirements.

The take up of the CPD program in Ireland for those with jobs looking to make a career change into pharmaceuticals only comprises of 4% of our trainees. Those who are in employment have to self-fund on my programs, as Government funding is only available for the unemployed.

Even in the case of reskilled workers who have successfully gone through my CPD program under Springboard only 2% of these go onto further CPD programs (or complete the full BSc degree) after securing employment. It appears that whilst a knowledge-based economy requires lifelong learning initiatives for its citizens in order to succeed, many technical workers do not want to invest their time and effort into technical learning programs after employment is secured. These workers appear to be willing to complete technical programmes as a means to an end (i.e. get a job, secure a promotion, earn more money) but not to become a more skilled/proficient worker (master craftsman).

I have also observed that whilst pharmaceutical companies have hired large numbers of Springboard graduates from my CPD program since 2011 and their CPD qualification was a key part of the hiring decision, these companies do not appear to have incentivized these new hires to complete more of my CPDs. Likewise even with these large numbers of new employees successfully absorbed into the industry, the companies have looked for their existing operators and technicians without these qualifications to undergo similar technical development CPD programs.

It appears that whilst the Government’s Springboard initiative supports the idea of building a knowledge based economy through the lifelong learning of its citizens, neither the employers nor the workers appear to want to invest the time and effort in it through more CPD programs once the resource is hired or the job is secured. I question if a nation can develop a knowledge-based economy without the emotional support of its citizens and employers for lifelong learning. Therefore is lifelong learning a real self-sustaining entity or does it is require to be continually hooked up to a Government life-support system to survive?

The economic context, narrative and elements of the Irish case study are summarised in Table 1.

The Singapore Case

The Singapore Government decided in the late 1990s that pharmaceuticals would become the 4th pillar of the economy, The BioMedical Science sector (BMS) has rapidly grown in Singapore and in 2014 BMS manufacturing output had increased to $6 billion and was employing 6,000 workers (Singapore EDB, 2013).

The success in creating a pharmaceuticals sector has also supported the Government strategy for creating a knowledge-based economy with high paying jobs and significant capital investment.

In 2007 Government was also planning to establish a national competency framework for all industry sectors, the Workforce Skills Qualification (WSQ). Pharmaceuticals were seen as a key sector in this, even though the direct employment numbers at the time were only 3,000 workers (Dept. of Statistics Singapore, 2015). Singapore was also looking for mechanisms to transition workers from their electronics manufacturing sector (which was in decline) into this hi-tech highly regulated industry sector, which was to become the 4th pillar of the economy (Singapore EDB, 2013).

Around that time the Singapore Government became aware of my initiative in Ireland to create a pool of experienced workers from other industry sectors to transition into the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. I was invited to bring my initiative to Singapore, as they were facing similar problems with workforce shortages in their pharmaceutical manufacturing sector.

The Singapore Government reacted immediately to the economic downturn in 2008 with a significant investment in training and skills upgrading for the workforce to better weather the economic storm. Working adults took advantage of upgrading and retraining programmes so as to remain relevant and employable in the job market under the Skills Programme for Upgrading and Resilience (SPUR) initiative. SPUR leveraged on the extensive CET (Continuing Education & Training) system already in place to scale-up training programmes and help companies and workers during the economic downturn, building stronger manpower capabilities for the recovery. The modules from the DIT BSc programme which had been aligned with the WSQ competency framework were included under the SPUR initiative of 800 courses which workers could avail of for two years from 2008-2010 (Singapore ESC, 2010).

Whilst this was a very innovative response from the Singaporean Government to the 2008 Global Downturn the response of the Irish Government to initially withdraw funding from training initiatives when the downturn happened seems very short sighted in comparison. It is important to also view this decision in the light of the fact that there is no unemployment benefit structure in Singapore, unlike Ireland. Hence in Ireland the Government had a legal requirement to use available budgets to first pay unemployment benefits to workers who were retrenched. In Singapore the social and political consequences of workers being retrenched without any income from unemployment benefits had to be addressed. Hence the equivalent of these ‘unemployment benefits’ were invested in an innovative and practical way to the benefit of its citizens through the SPUR programme and without creating the ‘sense of entitlement’ associated with social welfare programmes in other countries.

During the two years of SPUR, over 250 workers completed my pharmaceutical re- skilling CPD programme and 75% of these workers successfully transitioned into employment both directly with pharmaceutical manufacturing companies or into the network of supporting companies which are part of the overall pharmaceutical industry ecosystem.

Interestingly, by 2010 the Singapore economy had recovered from the Global downturn and it led the first world countries with a return to pre-2008 unemployment levels of less than 3%. When this happened SPUR funding was discontinued and a new training framework SkillsConnect was introduced which was less inclusive than SPUR. A key difference was the change from creating a pool of talent from which industry could select employees (i.e. a “Train and Place” model) to one where re- skilling was only offered to workers who had already secured placement with a company, i.e. using a “Place and Train” model. Enrolment on this program was predominantly for company employees rather than those who wanted to acquire the skills and qualifications to make a career change before they had secured a job in the industry.

This new model would minimize the extent to which the tax-payer should be burdened with creating a pool of resources that industry may never use. It was founded on the belief that industry would hire the most suitable candidates available in the marketplace and it would be more efficient to only train those people.

Between 2011-2013 I observed the negative effect that this change of model had on the development of a knowledge based economy through lifelong learning of the workforce. Without access to a pool of talent the pharmaceutical companies reverted to the previous norm and hired new graduates from the universities for entry level roles into manufacturing – and hence the 250 trainee numbers from 2008-2010 who took these pharmaceutical cross training programmes dropped to twenty-five trainees per year from 2011-2013, even though the Singapore economy had fully recovered from the 2008 Global downturn and had moved beyond the cautious recovery phase and into strong growth like the rest of Asia.

The requirement that only workers who had already been placed in industry could access SPUR training diminished the opportunity for experienced workers to make a career change from ‘sunset industries’, (i.e. often low-tech companies which were in decline but still operating) into the hi-tech pharmaceutical sector that the Government wanted to develop as part of their knowledge based economy strategy. During the “Place and Train” years in Singapore from 2011 to 2013, I took the initiative to transition the classroom materials for my industry specific modules into an online delivery format. This was a co-funded initiative with SPRING Singapore (a Government development agency) and the Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT) at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU). It was developed originally to give pharmaceutical manufacturing companies more flexibility in being able to release employees for training and hence increase employee numbers going through the WSQ programme, but the companies in Singapore were very slow to engage with this new online delivery format. However the Irish Government embraced it for their Springboard initiative in 2011.

The economic context, narrative and elements of the Singapore case study are summarised in Table 1.

The Puerto Rico Case

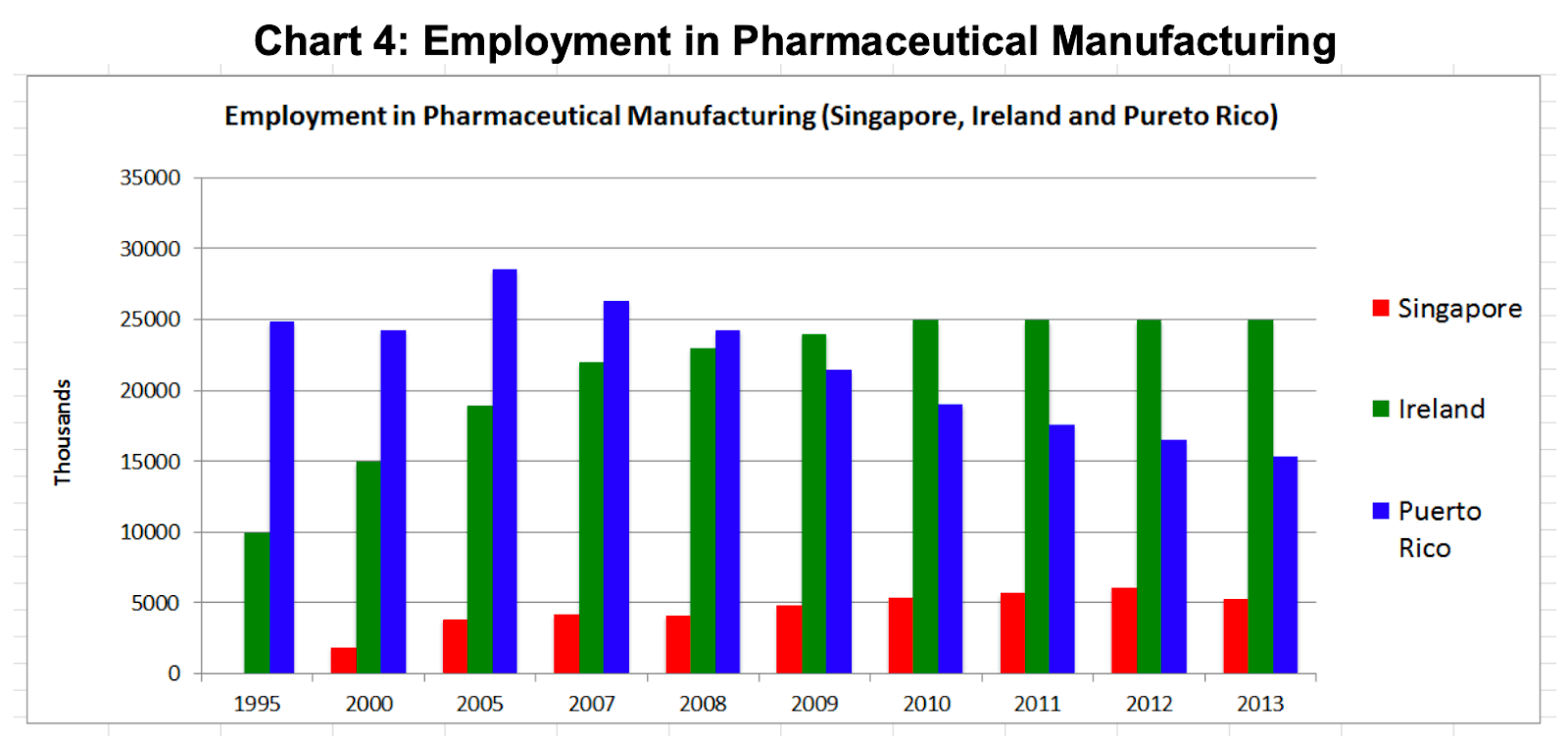

Manufacturing of pharmaceuticals began in Puerto Rico in the 1960’s and peaked in 1990, when it manufactured 80% of the major prescription drugs for the U.S. market. At that time it had very favourable tax concessions for US based companies and those were ended 15 years later in 2006 when direct employee numbers in pharmaceutical manufacturing were 28,000 people in Puerto Rico as compared to Ireland (18,000) and Singapore (3,000) (The National Puerto Rican CoC, 2015).

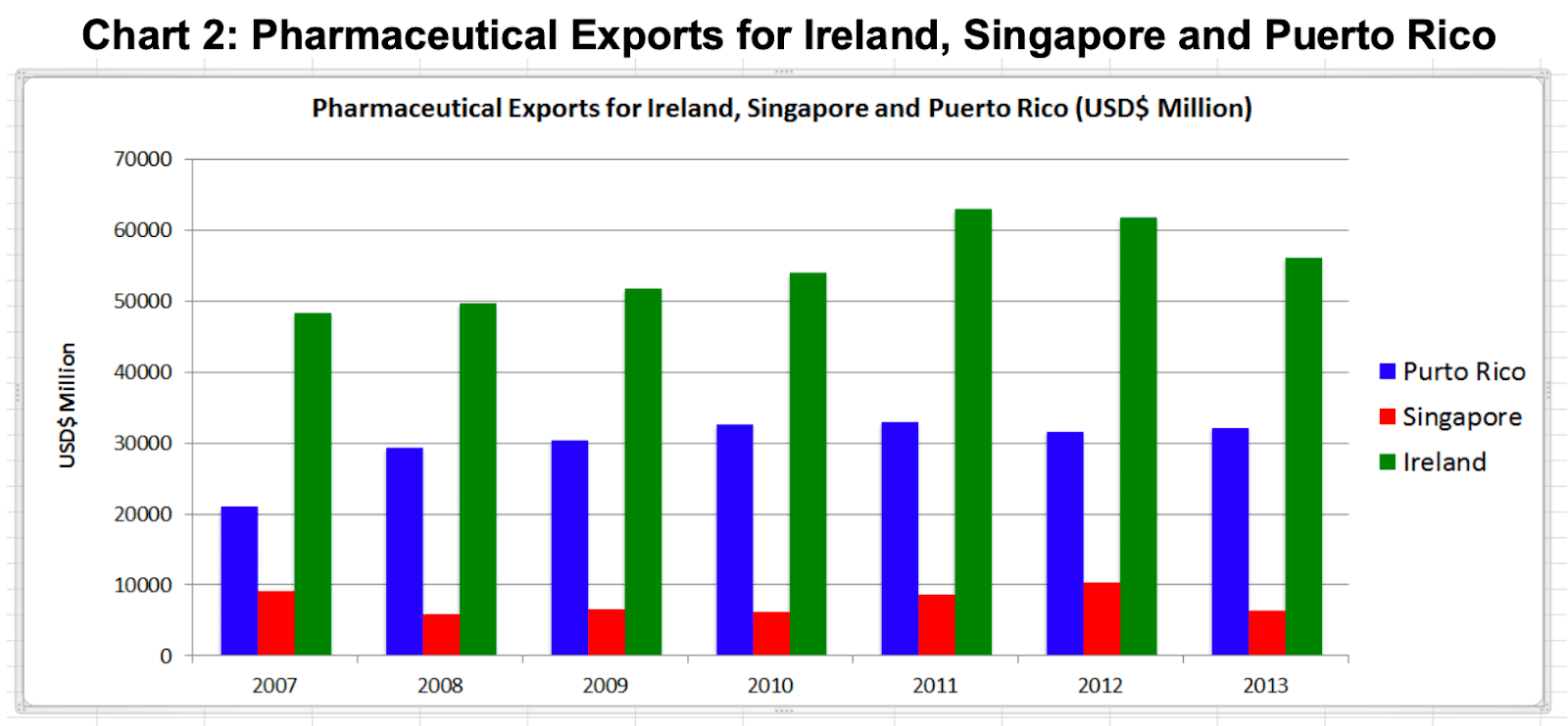

By 2013, employee numbers in Puerto Rico had fallen to 16,000 whilst there had been significant growth in Ireland (25,000) and Singapore (6,000) during the same period. In 2013 the value of pharmaceutical exports from Puerto Rico was $32billion as compared to Ireland ($56billion) and Singapore ($6billion). Once a significantly bigger manufacturing hub than Ireland, Puerto Rico now has significantly diminished to 60% of Ireland’s size but it is still significantly bigger than Singapore.

As a private training provider delivering technical CPD training for the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector, Puerto Rico is still a hugely relevant global manufacturing hub. Being a Commonwealth of the U.S., Puerto Rico is also uniquely positioned as it has US structures for education and lifelong learning of the workforce. It is also focussed on finding new ways to stop the erosion of their pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. The technical development of their workforce with internationally recognized qualifications is an element of their strategy (Fernandez, 2011).

In mid-2014 I approached the Council for Higher Education in Puerto Rico along with my partner and awarding body, the Dublin Institute of Technology, to apply for a licence to deliver our online BSc degree in Puerto Rico. This was of great interest to them as they recognized that a part-time online degree was not currently available in Puerto Rico for the experienced workforce in the Pharmaceutical industry.

They saw that the delivery format would allow experienced workers who are stuck at their current level within a company without a degree, to gain the academic qualifications necessary to climb up the career ladder and achieve their full potential for themselves and their companies. In addition they saw the productivity benefits for Puerto Rico from developing these unrealized capabilities and skill sets in a mature workforce in their most important industry sector.

In June 2015 the Council for Higher Education approved our online BSc degree for delivery in Puerto Rico accredited by DIT, allowing the European entry and assessment requirements to be maintained in this US academic environment. This reflects the importance that they attributed to the development of their mature workforce and clearly demonstrates that negotiations in different locations can result in different outcomes, based on differing policies for a knowledge based economy. In Singapore it was not possible to get approval to deliver this degree, even though a number of the modules from it were being delivered under their WSQ framework.

The main learning from Puerto Rico to date have mainly been at the Government level in getting the degree approved. Data regarding the challenges of delivering academically accredited CPDs and BSc degree has only now started to be generated, with the first Puerto Rico employees commencing the BSc degree in October 2015. This will be the substance of a future paper.

The economic context, narrative and elements of the Puerto Rico case study are summarised in Table 1.

Cross-Comparison of Cases

Bereday (Bereday,1964) suggests that setting cases out in juxtaposition using criteria or variables that emerge naturally from the data will identify areas of convergence and areas of difference. Following this process the variables and findings are presented in tabular form below.

| Variable | Ireland | Singapore | Puerto Rico |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model of K-E (knowledge economy) promoted by Government. | Lifelong learning (LLL) was initially promoted as a co- funded general training program for all citizens and companies across all areas of the economy during the pre-2008 boom times. It was refocused as a fully funded sectoral job training for unemployed workers during the post 2008 Global Economic downturn. | LLL was promoted as a 90% co-funded training program to up-skill all workers with the competency skills necessary for their sector, aligned with the WSQ framework. In 2008 this was a “Train and Place” program (SPUR) where workers could choose to be funded to re- skill. In 2010 after full recovery from the Global Economic downturn this changed to the SkillsConnect program which was a “Place and Train” initiative where funding was predominantly available through companies and not directly to the workers. In 2015, a new initiative was approved to fund mid- career changes for those 40-years and older. | Observed the importance that the Council for Higher Education attributed to the development of their mature workforce to realize national productivity benefits, through their flexibility in the approval process of our online BSc degree, as it was a unique offering not currently available in Puerto Rico for their workforce. |

| Sectors selected for promotion. | Only selected hi- tech industries that could generate employment and benefit the economy. | All sectors of the economy. | Only observed the pharmaceutical sector for promotion to date. |

| Education and training supports to achieve a K-E | Fully funded for unemployed workers looking to transition into selected hi-tech industries. No funding for workers looking for a mid- career change into these selected sectors if they are in employment. | After 2010, predominantly co- funded training for employers to up-skill their existing and new workforce. Little available funding for workers looking for a mid-career change. In 2015, a new initiative was approved to fund mid- career changes for those 40-years and older. | Observed that Government funding is not generally available for lifelong learning initiatives (except for the GI Bill for Veterans). |

| Types of training funded | Part-time, not greater than one year academically accredited CPD (minor awards) and Degrees (major awards). | Part-time competency based training courses approved under the WSQ framework with qualifications awarded through the Workforce Development Agency (WDA). These qualifications are not linked to the academic framework and are only recognized within Singapore. | Individual company plans recompense workers after successfully completing approved programs. |

| Supports for recently unemployed | Social welfare unemployment payments and reskilling into selected hi-tech industries. | Reskilling after securing placement in a new company/industry. Unemployment payments are not part of the social welfare structure. | Limited supports for short periods of time (except for Veterans). |

| Attitude of pharma companies to training and LLL | Appear to have low interest in incentivizing their employees along the path of lifelong learning with further technical development through my academically accredited CPD’s. | Appear to have low interest in incentivizing their employees along the path of life-long learning with further technical development through my competency based WSQ programs. | Enthusiastic about the possibility of unlocking the potential of experienced workers whose career progression is limited due to the lack of a degree. |

| Attitude of pharma workers to CPD and LLL | Appear to have low interest in investing their time and effort into technical life-long learning programs for my additional CPD or BSc qualifications after employment is secured. | Appear to have low interest in investing their time and effort into technical life-long learning programs for my additional WSQ qualifications after employment is secured. | Data regarding the challenges of delivering academically accredited CPD’s and BSc degree has only now started to be generated, with the first Puerto Rico employees commencing the BSc degree in October 2015. |

| Attitude of Government to private CPD providers | Inclusion of private CPD providers alongside academic institutions into the public tendering process for delivery of academically accredited CPD and degree programs. | Inclusion of private CPD providers alongside academic institutions into the public tendering process for delivery of competency based WSQ programs. | Flexible to new ways of doing things at the Council for Higher Education level. |

The Bereday approach shows divergence on the first five variables above, which is not unexpected given the different social and political models of the three-countries analysed. The data for Puerto Rico will grow over time with student numbers and their feedback and the feedback from their employers, both directly and indirectly. Approval for delivery of the online BSc degree was only received in June 2015 with the first Puerto Rico employees commencing their degree in October 2015. Hence my significant interactions have been limited to the Government approval process and initial company meetings to discuss the roll-out of this online degree to their employees.

The most interesting finding in the table above is the convergence between Ireland and Singapore on Variables 6 and 7 across 1500 workers and fifty companies in multiple locations in both of these centres of excellence for manufacturing in a hi- tech highly regulated environment. Both the companies and the workers appear to be disinterested in engaging in the lifelong learning initiatives of both Governments with a view to developing a knowledge-based economy, for the overall benefit of their nations and their citizens. Neither the employers nor the workers appear to want to invest their time and effort in lifelong learning once the resource is hired or the job is secured.

This finding warrants further study across other hi-tech industries to determine if this is a sectoral anomaly, as the companies in this study are predominantly multinationals with manufacturing locations in all of the three locations. However I question if a nation can develop a knowledge-based economy without the emotional support of its citizens and employers for lifelong learning.

Implications for Private Training Providers from Three Cases

Private training providers have to mediate multiple political, academic and cultural contexts. They also have to mediate academic and pedagogical context which vary considerably even at the micro level. Adapting to the three case study context in this paper included meeting the expectations of stakeholders and continuously adapting to local nuances. Table 2 below summarises how adaptations were made.

| Variable | Ireland | Singapore | Puerto Rico |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapting to expectations of Government from a private provider |

|

|

|

| Meeting the expectations of academic partners | Approval of partnership agreement through formal twelve month process | No academic partner | No academic partner |

| Meeting expectations of pharma companies |

| Industry inputs and approvals required during program development | Review panel representatives from Industry and Academia in approval of BSc degree |

| Meeting the expectations of workers making a mid-career change and wishing to re- skill for the pharma sector |

|

|

|

The Bereday approach shows divergence on the first two variables above, which is not unexpected given the different Government dynamics of the three-countries). Likewise the convergence on Variables 3 and confirms the commonality across the workers and the companies, predominantly multinational, of what they expect from a CPD provider, which is independent of the social and political models of the three- countries studied.

Concluding Comments

In conclusion, the paper offers tentative findings in the forms of insights into the dynamics of CPD provision for particular sectors where undulations in local economic policies and strategic planning can present both risks and rewards for the sector and for the providers of training. It also comments on the impact of tensions among differing understandings of policies for a knowledge-based economy and the likely long-term impact of these tensions for training provision in the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector into the future.

The insights have been generated during this ten year analysis of three cases in the pharmaceutical sector, primarily from Ireland and Singapore and now beginning in Puerto Rico. These have come from training and educating 1500 workers, interfacing and negotiating with numerous Government agencies in three countries and meeting with fifty multinational pharmaceutical manufacturing companies.

This body of knowledge has led to interesting insights and hypotheses into lifelong learning of technical workers in the hi-tech pharmaceutical industry. Future studies of other technical industries can examine if these finding about lifelong learning and its relationship to a knowledge based economy can be extrapolated. However a key question arising that is worthy of serious discussion and further study is:

If the case for creating a knowledge economy for the benefit a nation and its citizens is valid, and the case for lifelong learning of the workforce is an essential element of the creation of a knowledge economy, and the data for a hi-tech industry (Pharmaceuticals) across different global locations is to be considered, then neither the workforce not its employers appear to be sufficiently self-motivated to access the current structures and incentives of life-long learning to generate more skilled/proficient workers (master craftsmen) to the benefit of the company, for the sense of personal achievement of the worker or to achieve a productivity benefit for the overall economy. Therefore the case for the legislation of lifelong learning for both companies and the workforce in certain industry sectors which could benefit a nation and its people should be given strong consideration.

Bibliography

Bereday, G.Z.F. (1964). Comparative methods in education. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Bereday, G.Z.F. (1967) ‘Reflections on comparative methodology on education’.1964-1966, Volume Number 3, June 1967, pp 169-187.

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico Planning Board. (2009).Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Puerto Rico Fiscal Year 2009-2010. Available: http://www.jp.gobierno.pr/Portal_JP/Portals/0/CEDS/CEDS%20report_aug%2027- 09%20Version%20final.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico Planning Board. (2014).Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Puerto Rico Fiscal Year 2014-2015. Available: http://gis.jp.pr.gov/Externo_Econ/CEDS/CEDS%20FY%202014- %20FINAL%20%C2%AE%20(May%202014).pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

Deloitte. (2013).Operating Under Consent Decree: Managing a Life Sciences Company through a Major Regulatory Action. Available: http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/strategy/us-cons- consent-decree-01292014-final.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

Department of Statistics Singapore. (2015).M354901 – Employment in Manufacturing By Industry Cluster, Annual. Available: www.singstat.gov.sg. Last accessed September 2015.

Department of Statistics Singapore. (2015). M850581 – Singapore Residents Aged 25 Years & Over By Highest Qualification Attained, Sex, and Age Group, Annual. Available: www.singstat.gov.sg. Last accessed September 2015.

Fernandez, Daneris. (2011). The Economic Perspective of Pharmacy Between Jobs & Cost : Current Situation of the Pharmaceutical Industry in Puerto Rico. Available: http://www.camarapr.org/PRHealth2011/presentations/PRH&I- Daneris_Fernandez.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

Greenspan, Alan. (2005). Testimony of Chairman Alan Greenspan on Economic Outlook Before Joint Economic Committee, US Congress. Available: http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/testimony/2005/20051103/default.htm. Last accessed September 2015.

IDA Ireland. (2015). The Pharma Factor. Available: http://www.idaireland.com/newsroom/the-pharma-factor/. Last accessed September 2015.

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations. (2013).The Pharmaceutical Industry and Global Health: Facts and Figures 2012. Available: http://www.ifpma.org/fileadmin/content/Publication/2013/IFPMA_- _Facts_And_Figures_2012_LowResSinglePage.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

1189

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations. (2015).The Pharmaceutical Industry and Global Health: Facts and Figures 2014. Available: http://www.lif.se/globalassets/pdf/rapporter-externa/ifpma-facts-and- figures-2014.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

Jones, Kevin C. (2006).Puerto Rico’s Pharmaceutical Industry : 40 Years Young!. Available: http://www.pharmaceuticalonline.com/doc/puerto-ricos- pharmaceutical-industry-40-years-0003. Last accessed September 2015.

McClellan, Mark B. (2004). Statement on the Cost of Prescription Drugs before Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.Available: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Testimony/ucm114800.htm. Last accessed September 2015.

PharmaChemical Ireland. (2010). Innovation and Excellence : PharmaChemical Ireland Strategic Plan. Available: http://www.pharmachemicalireland.ie/Sectors/PCI/PCI.nsf/vPages/PCI_policy~Public ations_and_Resources~pharmachemical-ireland-strategy–innovation-and- excellence/$file/Innovation%20and%20Excellence%20Re. Last accessed September 2015.

Robson, Colin (2011). Real World Research 3rd Edition. United Kingdom: Wiley.

Rooney, Pauline. (2005). ‘Researching from the Inside – Does it Compromise

Validity?’ Dublin Institute of Technology online journal Level3 Issue 3, June 2005.

Shanmugaratnam, Tharman Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance. (2015). Speech by Mr. Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance at the Launch of GSK’s New Global Headquarters for Asia. Available: http://www.mof.gov.sg/Newsroom/Speeches. Last accessed September 2015.

Singapore Economic Development Board. (2013).Singapore Biotech Guide 2013/2014 : Overview of Singapore’s Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Industry. Available: http://www.pharmacy.nus.edu.sg/programmes/BScPharm/Sg%20BioTech%201314 %20ED04_EDB%20BMS.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

Singapore Economic Strategies Committee. (2010). High Skilled People. Innovative Economy. Distinctive Global City. Available: http://www.ecdl.org/media/Singapore%20Economic%20Committe_2010.pdf. Last accessed October 2015.

The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce. (2015). Puerto Rico’s Economy: A brief history from the 1980s to today and policy recommendations for the future. Available: http://nprchamber.org/files/3-19-15-Puerto-Rico-Economic- Report.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.

The Stationery Office. (2014). A Strategy for Growth : Medium-Term Economic Strategy 2014 – 2010.Available: http://mtes2020.finance.gov.ie/. Last accessed September 2015.

The Stationary Office. (2006). Strategy for Science Technology and Innovation 2006- 2013 Available: https://www2.ul.ie/pdf/35659989.pdf. Last accessed October 2015.

Van Egeraat, Chris and Barry, Frank. (2006). The Irish Pharmaceutical Industry over the Boom Period and Beyond. Available: https://www.tcd.ie/business/staff/fbarry/papers/The%20Irish%20Pharmaceutical%20I ndustry%20over%20the%20Boom%20Period%20and%20Beyond.pdf. Last accessed September 2015.